Free love

Much of the free love tradition reflects a liberal philosophy that seeks freedom from state regulation and church interference in personal relationships.

[6] By whatever name, advocates had two strong beliefs: opposition to the idea of forced sexual activity in a relationship and advocacy for a woman to use her body in any way that she pleases.

[7] Laws of particular concern to free love movements have included those that prevent an unmarried couple from living together, and those that regulate adultery and divorce, as well as age of consent, birth control, homosexuality, abortion, and sometimes prostitution; although not all free-love advocates agree on these issues.

Access to birth control was considered a means to women's independence, and leading birth-control activists also embraced free love.

To help achieve this goal, such radical thinkers relied on the written word, books, pamphlets, and periodicals, and by these means the movement was sustained for over fifty years, spreading the message of free love all over the United States.

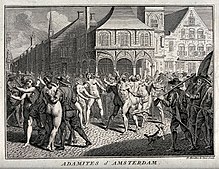

[20] Typical of such movements, the Cathars of 10th to 14th century Western Europe freed followers from all moral prohibition and religious obligation, but respected those who lived simply, avoided the taking of human or animal life, and were celibate.

The Cathars and similar groups (the Waldenses, Apostle brothers, Beghards and Beguines, Lollards, and Hussites) were branded as heretics by the Roman Catholic Church and suppressed.

[21] [22] There were also perceptive critiques, within these radical movements, such as by Gerrard Winstanley: The mother and child begotten in this manner is like to have the worst of it, for the man will be gone and leave them ... after he hath had his pleasure.

"[8] Wollstonecraft felt that women should not give up freedom and control of their sexuality, and thus did not marry her partner, Gilbert Imlay, despite the two conceiving and having a child together in the midst of the Terror of the French Revolution.

[24] At a time of tremendous strain in his marriage, in part due to Catherine's apparent inability to bear children, he directly advocated bringing a second wife into the house.

[25] His poetry suggests that external demands for marital fidelity reduce love to mere duty rather than authentic affection, and decries jealousy and egotism as a motive for marriage laws.

In an act understood to support free love, the child of Wollstonecraft and Godwin, Mary, took up with the then still-married English romantic poet Percy Bysshe Shelley in 1814 at the young age of sixteen.

Fellow social reformer and educator Mary Gove Nichols was happily married (to her second husband), and together they published a newspaper and wrote medical books and articles.

Incorporating influences from the writings of the English thinkers and activists Edward Carpenter and Havelock Ellis, women such as Emma Goldman campaigned for a range of sexual freedoms, including homosexuality and access to contraception.

Dorothy Day also wrote passionately in defense of free love, women's rights, and contraception—but later, after converting to Catholicism, she criticized the sexual revolution of the sixties.

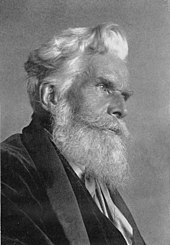

[40] Fellowship members included many illustrious intellectuals of the day, who went on to radically challenge accepted Victorian notions of morality and sexuality, including poets Edward Carpenter and John Davidson, animal rights activist Henry Stephens Salt,[41] sexologist Havelock Ellis, feminists Edith Lees, Emmeline Pankhurst and Annie Besant and writers H. G. Wells, Bernard Shaw, Bertrand Russell and Olive Schreiner.

Russell consistently addressed aspects of free love throughout his voluminous writings, and was not personally content with conventional monogamy until extreme old age.

Russell argued that the laws and ideas about sex of his time were a potpourri from various sources, which were no longer valid with the advent of contraception, as the sexual acts are now separated from the conception.

[46] A decade later, the book cost him his professorial appointment at the City College of New York due to a court judgment that his opinions made him "morally unfit" to teach.

He argued that it was, in general, impossible to sustain this mutual feeling for an indefinite length of time, and that the only option in such a case was to provide for either the easy availability of divorce, or the social sanction of extra-marital sex.

Armand seized this opportunity to outline his theses supporting revolutionary sexualism and camaraderie amoureuse that differed from the traditional views of the partisans of free love in several respects.

[51] "The camaraderie amoureuse thesis", he explained, "entails a free contract of association (that may be annulled without notice, following prior agreement) reached between anarchist individualists of different genders, adhering to the necessary standards of sexual hygiene, with a view toward protecting the other parties to the contract from certain risks of the amorous experience, such as rejection, rupture, exclusivism, possessiveness, unicity, coquetry, whims, indifference, flirtatiousness, disregard for others, and prostitution.

[51] In a text from 1937, he mentioned among the individualist objectives the practice of forming voluntary associations for purely sexual purposes of heterosexual, homosexual, or bisexual nature or of a combination thereof.

He also supported the right of individuals to change sex and stated his willingness to rehabilitate forbidden pleasures, non-conformist caresses (he was personally inclined toward voyeurism), as well as sodomy.

[51] His militancy also included translating texts from people such as Alexandra Kollontai and Wilhelm Reich and establishments of free love associations which tried to put into practice la camaraderie amoureuse through actual sexual experiences.

Free love advocacy groups active during this time included the Association d'Études sexologiques and the Ligue mondiale pour la Réforme sexuelle sur une base scientifique.

[52] Zetkin also recounted Lenin's denunciation of plans to organise Hamburg's women prostitutes into a "special revolutionary militant section": he saw this as "corrupt and degenerate".

The Soviet government abolished centuries-old Czarist regulations on personal life, which had prohibited homosexuality and made it difficult for women to obtain divorce permits or to live singly.

Despite the developing sexual revolution and the influence of the Beatniks in this new counterculture social rebellion, it has been acknowledged that the New Left movement was arguably the most prominent advocate of free love during the late 1960s.

[54] Images from the pro-socialist May 1968 uprising in France, which occurred as the anti-war protests were escalating throughout the United States, would provide a significant source of morale to the New Left cause as well.