Aunt Jemima

"[5] Nancy Green portrayed the Aunt Jemima character at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago and was one of the first Black corporate models in the United States.

[1][2][13] To distinguish their pancake mix, in late 1889 Rutt appropriated the Aunt Jemima name and image from lithographed posters seen at a vaudeville house in St. Joseph, Missouri.

[1][3][13] Quaker Oats commissioned Haddon Sundblom, a nationally known commercial artist, to paint a portrait of an obese actress named Anna Robinson, and the Aunt Jemima package was redesigned around the new likeness.

[1][17] James J. Jaffee, a freelance artist from the Bronx, New York, also designed one of the images of Aunt Jemima used by Quaker Oats to market the product into the mid-20th century.

[1][18][19][20] In 1989, marking the 100th anniversary of the brand, her image was again updated, with all head-covering removed, revealing wavy, gray-streaked hair, gold-trimmed pearl earrings, and replacing her plain white collar with lace.

At the time, the revised image was described as a move towards a more "sophisticated" depiction, with Quaker marketing the change as giving her "a more contemporary look" which remained on the products until early 2021.

[18][19] On June 17, 2020, Quaker Oats announced that the Aunt Jemima brand would be discontinued and replaced with a new name and image "to make progress toward racial equality".

[5] Aunt Jemima is based on the common enslaved "Mammy" archetype, a plump black woman wearing a headscarf who is a devoted and submissive servant.

Rutt reportedly saw a minstrel show featuring the "Old Aunt Jemima" song in the fall of 1889, presented by blackface performers identified by Arthur F. Marquette as "Baker & Farrell".

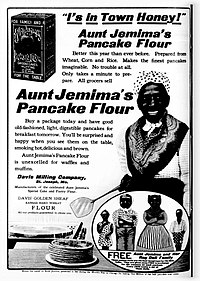

[17] Marketing materials for the line of products centered around the "Mammy" archetype, including the slogan first used at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois: "I's in Town, Honey".

[41] A typical magazine ad from the turn of the century created by advertising executive James Webb Young, and the illustrator N.C. Wyeth,[37] shows a heavyset black cook talking happily while a white man takes notes.

The ad copy says, "After the Civil War, after her master's death, Aunt Jemima was finally persuaded to sell her famous pancake recipe to the representative of a northern milling company.

[32][38] The marketing legend surrounding Aunt Jemima's successful commercialization of her "secret recipe" contributed to the post-Civil War nostalgia and romanticism of Southern life in service of America's developing consumer culture—especially in the context of selling kitchen items.

Wells was incensed by the exclusion of African Americans from mainstream fair activities; the so-called "Negro Day" was a picnic held off-site from the fairgrounds.

[38] Black scholars Hallie Quinn Brown, Anna Julia Cooper, and Fannie Barrier Williams used the World's Fair as an opportunity to address how African American women were being exploited by white men.

[38] Aunt Jemima embodied a post-Reconstruction fantasy of idealized domesticity, inspired by "happy slave" hospitality, and revealed a deep need to redeem the antebellum South.

In this context, the slang term "Aunt Jemima" falls within the "mammy archetype" and refers to a friendly black woman who is perceived as obsequiously servile or acting in, or protective of, the interests of whites.

[43] John Sylvester of WTDY-AM drew criticism after calling Condoleezza Rice an "Aunt Jemima" and Colin Powell an "Uncle Tom", referring to remarks by singer and civil rights activist Harry Belafonte about their alleged subservience in the George W. Bush administration.

[44] Barry Presgraves, then 77-year-old Mayor of Luray, Virginia, was censured 5-to-1 by the town council because he referred to Kamala Harris as "Aunt Jemima" after she was selected by Joe Biden to be the Democratic Party vice presidential candidate.

[45][46][47][48] The African American Registry of the United States suggests Nancy Green and others who played the caricature of Aunt Jemima[23] should be celebrated despite what has been widely condemned as a stereotypical and racist brand image.

Advertising agencies (such as J. Walter Thompson, Lord and Thomas, and others) hired dozens of actors to portray the role, often assigned regionally, as the first organized sales promotion campaign.

She appeared at fairs, festivals, flea markets, food shows, and local grocery stores, her arrival heralded by large billboards featuring the caption, "I'se in town, honey.

[63] Her $1,200 total payment in 1939 (equivalent to $26,285 in 2023) was almost the entirety of the household's annual income[63] and stood in stark contrast to the official Aunt Jemima history timeline, which stated that Robinson was "able to make enough money to provide for her children and buy a 22-room house where she rents rooms to boarders".

[64] The same claim was made for Anna Short Harrington, yet according to the 1940 census, she rented an apartment in a four-flat in Washington Park with her daughter, son-in-law, and two grandchildren.

Aunt Jemima has been a present image identifiable by popular culture for well over a century, dating back to Nancy Green's appearance at the 1893 World Fair in Chicago, Illinois.

In the 1960s, Betye Saar began collecting images of Aunt Jemima, Uncle Tom, Little Black Sambo, and other stereotyped African-American figures from folk culture and advertising of the Jim Crow era.

In this mixed-media assemblage, Saar utilized the stereotypical mammy figure of Aunt Jemima to subvert traditional notions of race and gender.

: The Confederate States of America features numerous depictions of Aunt Jemima-type characters as slaves (referred to as servants) in an alternate timeline in which the Confederacy won the American Civil War.

[citation needed] In the South Park episode "Gluten Free Ebola" (2014), Aunt Jemima appears in Eric Cartman's delirious dream to tell him that the food pyramid is upside down.

[85] On November 7, 2020, the comedy sketch TV series Saturday Night Live featured a skit in which Aunt Jemima was fired, in addition to Uncle Ben, with roles played by "Count Chocula" and the "Allstate Guy".