Australian Air Corps

The corps' primary purpose was to maintain assets of the Central Flying School at Point Cook, Victoria, but several pioneering activities also took place under its auspices: AAC personnel set an Australian altitude record that stood for a decade, made the first non-stop flight between Sydney and Melbourne, and undertook the country's initial steps in the field of aviation medicine.

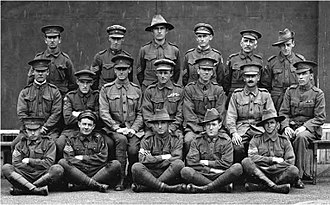

[10] In August 1919, several senior AFC pilots, including Lieutenant Colonel Oswald Watt, Major Anderson, and Captain Roy Phillipps, were appointed to serve on a committee examining applications for the AAC.

[12] Roy King, the AFC's second highest-scoring fighter ace after Harry Cobby, refused an appointment in the AAC because it had not yet offered a commission to Victoria Cross recipient Frank McNamara.

[11][13] In a letter dated 30 January 1920, King wrote, "I feel I must forfeit my place in favor (sic) of this very good and gallant officer"; McNamara received a commission in the AAC that April.

[14] Captain Hippolyte "Kanga" De La Rue, an Australian who flew with the RNAS during the war, was granted a commission in the AAC because a specialist seaplane pilot was required for naval cooperation work.

Anderson's aircraft landed near Hobart in the evening, having failed to locate the lost schooner, but Stutt and Dalzell were missing; their DH.9A was last sighted flying through cloud over Bass Strait.

The court proposed compensation of £550 for Stutt's family and £248 for Dalzell's—the maximum amounts payable under government regulations—as the men had been on duty at the time of their deaths; Federal Cabinet increased these payments three-fold.

[20] In February 1920, the Vickers Vimy bomber recently piloted by Ross and Keith Smith on the first flight from England to Australia was flown to Point Cook, where it joined the strength of the AAC.

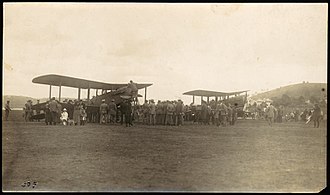

[21] In March 1920, Australia began receiving 128 aircraft with associated spares and other equipment as part of Britain's Imperial Gift to Dominions seeking to establish their own post-war air services.

The effects of hypoxia exhibited by Cole and De La Rue intrigued the medical officer, Captain Arthur Lawrence, who subsequently made observations during his own high-altitude flight piloted by Anderson; this activity has been credited as marking the start of aviation medicine in Australia.

[24] A few days earlier, Williams and Wackett had flown two DH.9As to the Royal Military College, Duntroon, to investigate the possibility of taking some of the school's graduates into the air corps, a plan that came to fruition after the formation of the RAAF.

In August, the AAC was called upon at the last minute to fly the Prince's mail from Port Augusta, South Australia, to Sydney before he boarded Renown for the voyage back to Britain.

Again Williams enlisted the services of former AFC personnel to make up for a shortfall in the number of AAC pilots and mechanics available to prepare and fly the nineteen aircraft allotted to the program.

The Second Peace Loan gave AAC personnel experience in a variety of flying conditions, and the air service gained greater exposure to the Australian public.