Australian English

Australian English began to diverge from British and Hiberno-English after the First Fleet established the Colony of New South Wales in 1788.

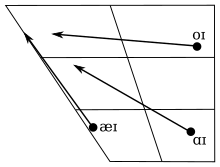

[8] Australian English differs from other varieties in its phonology, pronunciation, lexicon, idiom, grammar and spelling.

[9] Australian English is relatively consistent across the continent, although it encompasses numerous regional and sociocultural varieties.

"General Australian" describes the de facto standard dialect, which is perceived to be free of pronounced regional or sociocultural markers and is often used in the media.

[6] The earliest Australian English was spoken by the first generation of native-born colonists in the Colony of New South Wales from the end of the 18th century.

Peter Miller Cunningham's 1827 book Two Years in New South Wales described the distinctive accent and vocabulary that had developed among the native-born colonists.

[7] The first of the Australian gold rushes in the 1850s began a large wave of immigration, during which about two percent of the population of the United Kingdom emigrated to the colonies of New South Wales and Victoria.

An example was the introduction of vocabulary from American English, including some terms later considered to be typically Australian, such as bushwhacker and squatter.

Examples of this feature are the following pairings, which are pronounced identically in Australian English: Rosa's and roses, as well as Lennon and Lenin.

Throughout the majority of the country, the "flat" /æ/ of man is the dominant pronunciation for the a vowel in the following words: dance, advance, plant, example and answer.

The exception is the state of South Australia, where a more advanced trap-bath split is found, and where the dominant pronunciation of all the preceding words incorporates the "long" /aː/ of father.

The affixes -ary, -ery, -ory, -bury, -berry and -mony (seen in words such as necessary, mulberry and matrimony) can be pronounced either with a full vowel (/ˈnesəseɹiː, ˈmalbeɹiː, ˈmætɹəməʉniː/) or a schwa (/ˈnesəsəɹiː, ˈmalbəɹiː, ˈmætɹəməniː/).

Consequently, the geographical background of individuals may be inferred if they use words that are peculiar to particular Australian states or territories and, in some cases, even smaller regions.

Academic research has also identified notable sociocultural variation within Australian English, which is mostly evident in phonology.

The dialects of English spoken in the various states and territories of Australia differ slightly in vocabulary and phonology.

Distinctive grammatical patterns exist such as the use of the interrogative eh (also spelled ay or aye), which is particularly associated with Queensland.

[25] The increasing dominance of General Australian reflects its prominence on radio and television since the latter half of the 20th century.

Recent generations have seen a comparatively smaller proportion of the population speaking with the Broad sociocultural variant, which differs from General Australian in its phonology.

Academics have noted the emergence of numerous ethnocultural dialects of Australian English that are spoken by people from some minority non-English speaking backgrounds.

Research published in 1986, regarding vernacular speech in Sydney, suggested that high rising terminal was initially spread by young people in the 1960s.

[32] In the United Kingdom, it has occasionally been considered one of the variety's stereotypical features, and its spread there is attributed to the popularity of Australian soap operas.

[citation needed] "Mate" is also used in multiple ways including to indicate "mateship" or formally call out the target of a threat or insult, depending on internation and context.

[citation needed] Some elements of Aboriginal languages have been adopted by Australian English—mainly as names for places, flora and fauna (for example dingo) and local culture.

Many such are localised, and do not form part of general Australian use, while others, such as kangaroo, boomerang, budgerigar, wallaby and so on have become international.

The best-known example is the capital, Canberra, named after a local Ngunnawal language word thought to mean "women's breasts" or "meeting place".

[38] Some common examples are arvo (afternoon), barbie (barbecue), smoko (cigarette break), Aussie (Australian) and Straya (Australia).

Examples of grammatical differences between Australian English and other varieties include: As in all English-speaking countries, there is no central authority that prescribes official usage with respect to matters of spelling, grammar, punctuation or style.

[55] Unspaced forms such as onto, anytime, alright and anymore are also listed as being equally as acceptable as their spaced counterparts.

What are today regarded as American spellings were popular in Australia throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the Victorian Department of Education endorsing them into the 1970s and The Age newspaper until the 1990s.

The DD/MM/YYYY date format is followed and the 12-hour clock is generally used in everyday life (as opposed to service, police, and airline applications).