Austro-Italian ironclad arms race

A naval arms race between the Austrian Empire and Italy began in the 1860s when both ordered a series of ironclad warships, steam-propelled vessels protected by iron or steel armor plates and far more powerful than all-wood ships of the line.

The country quickly began a substantial construction program to bolster the Regia Marina, as the Italians believed that a strong navy would play a crucial role in making the recently unified kingdom a great power.

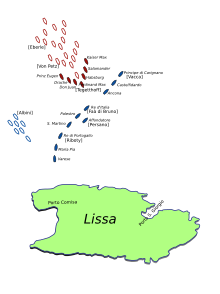

While Italy emerged on the winning side of the war and acquired the Kingdom of Lombardy–Venetia under the terms of the Treaty of Vienna, the Regia Marina was decisively defeated at the Battle of Lissa by the much smaller Imperial Austrian Navy.

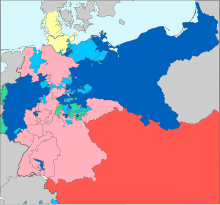

Both navies engaged in further construction projects throughout the 1870s and early 1880s, but the arms race ended in the 1880s due to the signing of the Triple Alliance between Italy, Austria-Hungary, and Germany in 1882 and the introduction of new technologies that led to the development of pre-dreadnought battleships.

Austrian field marshal Joseph Radetzky was unable to defeat the Venetian and Milanese insurgents in Lombardy–Venetia, and had to order his forces to evacuate western Italy, pulling his troops back to a chain of defensive fortresses between Milan and Venice known as the Quadrilatero.

[8] The Franco-Sardinian forces quickly defeated the Austrians during the spring of 1859 and after the Battle of Solferino, Austria ceded most of Lombardy and the city of Milan to France under the Treaty of Zürich, who transferred it to Sardinia in exchange for Savoy and Nice.

[10] Immediately after the Tuscan fleet had been integrated into the Royal Sardinian Navy, Cavour placed an order with the Société Nouvelle des Forges et Chantiers de la Méditerranée to construct two armored warships in Toulon.

[31] While foreign powers such as Austria watched the growth of Sardinia and the expansion of its army closely, the consolidation of the Sardinian Navy after the incorporation of multiple states across the Italian Peninsula received far less attention.

[44] While the Archduke had previously been given free rein over naval affairs, and had enjoyed an unprecedented allocation of new funds to complete his various expansion and modernization projects,[45] Austria's financial difficulties in the immediate aftermath of the war stalled his plans for the time being.

[32] When Garibaldi's conquest of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies began in May 1860, the Austrian Empire responded by recalling its small fleet stationed in the Levant under the command of Fregattenkapitän (Captain) Wilhelm von Tegetthoff.

[49] Sardinia's annexation of most of Central Italy in early 1860 had caused concern for the Austrian Empire, but the collapse of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies in just a matter of months sparked a diplomatic and military crisis in Vienna.

The Austrian Empire viewed Sardinian warships in the Adriatic as an overtly hostile act, and fears of Garibaldi continuing his military campaigns by attempting a landing in Istria or the Dalmatian Coast resulted in even greater alarm.

[50][51] These concerns were so great that in September 1860, Emperor Franz Joseph I issued an order to the Imperial Austrian Navy which stipulated that all Sardinian ships of any kind were to be barred entry into any Austrian-controlled port.

[46] This change signaled the direction of Italian foreign and naval policy in the years immediately after the formation of the Kingdom of Italy, as the ships were aimed at defeating the Imperial Austrian Navy in open combat.

Usually, the Austrian Navy would simply place an order for the vessels with a foreign shipyard, but the falling value of the florin in the years immediately after the war meant that Ferdinand Max could not follow Cavour's lead and seek to construct the ships he needed in another country.

Möring argued that new fortifications and coastal artillery would be sufficient to defend Austria's limited maritime interests and its coastline, and that the large sums of money Ferdinand Max supported spending on constructing ironclad warships would be better spent elsewhere.

Möring went so far as to publish a pamphlet attacking the Archduke's program outright, calling it a waste of Austrian finances and resources, while also arguing that an ironclad battle fleet would be of no value against Italy in the event of a war, as the decisive engagements Austria would fight in such a conflict would be on land.

These arguments were rebutted by Wickenbug and Degenfeld on the grounds that the Navy Law of 1850 had been amended in 1858, and that the large technological advancements which had played out since the First War of Italian Independence had likewise necessitated larger naval spending, as ironclads were far more expensive than traditional wooden ships.

They found opposition in Vice-Admiral Persano, who had won recognition for his efforts in blockading Ancona and Gaeta during Garibaldi's conquest of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies and the Sardinian invasion of the Papal States which followed.

In June, the Austrian Reichsrat approved Archduke Ferdinand Max's budget, but directed the Oberkommandant der Marine to cut expenditures not related to training, naval construction and ship maintenance.

Among those whose offers the Archduke had to reject for a lack of funds were American shipbuilder John Ericsson, the designer of USS Monitor, and the Arman Brothers shipyard in Bordeaux, which was constructing the Italian ironclad Ancona.

Ferdinand Max offered all 26 ships to Merton for roughly six million florins, enough to theoretically enable him to construct the one large armored frigate which could serve as the flagship of the Imperial Austrian Navy.

After appointing General Diego Angioletti to the office of Minister of the Navy, La Marmora worked the shrink the size of the Regia Marina's budget, and bring the era of overspending budgetary outlays to an end.

Using Spain's decision to finally recognize the Kingdom of Italy as a catalyst to begin debates over the size of the naval budget, La Marmora argued before the Chamber of Deputies that the Regia Marina possessed or had under construction more than enough warships of all types, including ironclads, to defeat the Imperial Austrian Navy in battle.

Nino Bixio, who had previously opposed the concept of ironclads only to enthusiastically endorse their acquisition by the Kingdom of Italy following the Battle of Hampton Roads, described the Regia Marina as "Incontestably superior" to the Imperial Austrian Navy.

Shortly after returning to Ancona with his fleet on 21 July however, Persano saw his story fall apart as the truth about the battle's results swiftly turned public opinion about the conduct of the Regia Marina against the Italian commander.

[181] Seizing upon the decline of the Regia Marina in the years immediately after the Battle of Lissa, Tegetthoff worked to continue the efforts of Archduke Ferdinand Max of expanding the ironclad fleet of the now Austro-Hungarian Navy.

The two believed that constructing new ironclad warships would rejuvenate Austria-Hungary's economy following the defeat at the hands of Prussia and Italy, and that such a fleet would help to open up new commercial opportunities in the Levant and the Middle East.

As the Regia Marina was still recovering from the political chaos which gripped its ranks after the defeat at Lissa two years earlier, this proposal presented the opportunity for Austria-Hungary to finally secure naval dominance over its Italian counterpart and put an end to the ironclad arms race which the two nations had been engaged in since 1860.

However, following the first dissolution of the League of the Three Emperors in 1878, Austro-Hungarian Foreign Minister Baron Heinrich Karl von Haymerle began negotiations with Rome to improve relations between Italy and Austria-Hungary.