Russo-Japanese War

The treaty recognized Japanese interests in Korea, and awarded to Japan Russia's lease on the Liaodong Peninsula, control of the Russian-built South Manchuria Railway, and the southern half of the island of Sakhalin (Karafuto).

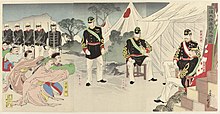

[11] Furthermore, the educational system of Meiji Japan was meant to train the schoolboys to be soldiers when they grew up, and as such, Japanese schools indoctrinated their students into Bushidō ("way of the warrior"), the fierce code of the samurai.

In 1884, Japan had encouraged a coup in the Kingdom of Korea by a pro-Japanese reformist faction, which led to the conservative government calling upon China for help, leading to a clash between Chinese and Japanese soldiers in Seoul.

[25] Meanwhile, Japan and Britain had signed the Anglo-Japanese Alliance in 1902 – the British seeking to restrict naval competition by keeping the Russian Pacific seaports of Vladivostok and Port Arthur from their full use.

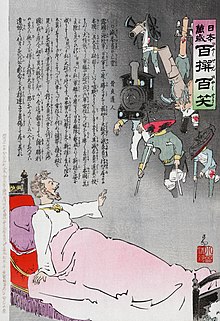

[32][need quotation to verify] The American president Theodore Roosevelt (in office 1901–1909), who was attempting to mediate the Russian–Japanese dispute, complained that Wilhelm's "Yellow Peril" propaganda, which strongly implied that Germany might go to war against Japan in support of Russia, encouraged Russian intransigence.

[41] In December 1903, Wilhelm wrote in a marginal note on a diplomatic dispatch about his role in inflaming Russo-Japanese relations:Since 97 – Kiaochow – we have never left Russia in any doubt that we would cover her back in Europe, in case she decided to pursue a bigger policy in the Far East that might lead to military complications (with the aim of relieving our eastern border from the fearful pressure and threat of the massive Russian army!).

Although certain scholars contend that the situation arose from the determination of Nicholas II to use the war against Japan to spark a revival in Russian patriotism, no historical evidence supports this claim.

On the night of 8 February 1904, the Japanese fleet under Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō opened the war with a surprise torpedo boat destroyer[70] attack on the Russian ships at Port Arthur.

Flying his flag in the French-built pre-dreadnought Tsesarevich, Vitgeft proceeded to lead his six battleships, four cruisers, and 14 torpedo boat destroyers into the Yellow Sea in the early morning of 10 August 1904.

[81] At approximately 12:15, the battleship fleets obtained visual contact with each other, and at 13:00 with Tōgō crossing Vitgeft's T, they commenced main battery fire at a range of about eight miles, the longest ever conducted up to that time.

By the end of May, the Second Pacific Squadron was on the last leg of its journey to Vladivostok, taking the shorter, riskier route between Korea and Japan, and travelling at night to avoid discovery.

After the Battle of Tsushima, a combined Japanese Army and Navy operation commanded by Admiral Kataoka Shichirō occupied Sakhalin Island to force the Russians into suing for peace.

The empire was certainly capable of sending more troops, but this would make little difference in the outcome due to the poor state of the economy, the embarrassing defeats of the Russian Army and Navy by the Japanese, and the relative unimportance to Russia of the disputed land, which made the war extremely unpopular.

After courting the Japanese, Roosevelt decided to support the Tsar's refusal to pay indemnities, a move that policymakers in Tokyo interpreted as signifying that the United States had more than a passing interest in Asian affairs.

George E. Mowry concludes that Roosevelt handled the arbitration well, doing an "excellent job of balancing Russian and Japanese power in the Orient, where the supremacy of either constituted a threat to growing America".

In Poland, which Russia partitioned in the late 18th century, and where Russian rule already caused two major uprisings, the population was so restless that an army of 250,000–300,000 – larger than the one facing the Japanese – had to be stationed to put down the unrest.

[109] Some political leaders of the Polish insurrection movement (in particular, Józef Piłsudski) sent emissaries to Japan to collaborate on sabotage and intelligence gathering within the Russian Empire and even plan a Japanese-aided uprising.

In the Russo-Japanese War, Japan had also portrayed a sense of readiness in taking a more active and leading role in Asian affairs, which in turn had led to widespread nationalism throughout the region.

The peace accord led to feelings of distrust, as the Japanese had intended to retain all of Sakhalin Island but were forced to settle for half of it after being pressured by the United States, with President Roosevelt opting to support Nicholas II's stance on not ceding territory or paying reparations.

The outcome of the Portsmouth peace negotiations, mediated by the U.S., was received by the general Japanese population with disbelief on September 5 and 6 when all the major newspapers reported the content of the signed treaty in lengthy editorials.

[115][clarification needed] Most army commanders had previously envisioned using these weapon systems to dominate the battlefield on an operational and tactical level but, as events played out, the technological advances forever altered the conditions of war too.

Joseph Bryant, writing in The Colored American Magazine, claimed that the Japanese victory marked "the beginning of a new era" and predicted that Japan's rise would mean the death of "absolute Aryan domination of the world" and that in the next century Asians, not Europeans, would lead civilization.

[130] And in partitioned Poland the artist Józef Mehoffer chose 1905 to paint his "Europa Jubilans" (Europe rejoicing), which portrays an aproned maid taking her ease on a sofa against a background of Eastern artefacts.

[112] As time went on, this feeling, coupled with the sense of "arrogance" at becoming a Great Power, grew and added to growing Japanese hostility towards the West, and fuelled Japan's military and imperial ambitions.

One of the earliest of several Russian songs still performed today was the waltz "Amur's Waves" (Amurskie volny), which evokes the melancholy of standing watch on the motherland far east frontier.

[155] The army surgeon Mori Ōgai kept a verse diary which tackled such themes as racism, strategic mistakes, and the ambiguities of victory, which has gained appreciation with historical hindsight.

[159] The French poet Blaise Cendrars was later to represent himself as on a Russian train on its way to Manchuria at the time in his La prose du Transsibérien et de la Petite Jehanne de France (1913) and energetically evoked the results of the war along the way: I saw the silent trains the black trains returning from the Far East and passing like phantoms ... At Talga 100,000 wounded were dying for lack of care I visited the hospitals of Krasnoyarsk And at Khilok we encountered a long convoy of soldiers who had lost their minds In the pesthouses I saw gaping gashes wounds bleeding full blast And amputated limbs danced about or soared through the raucous air[160] Much later, the Scottish poet Douglas Dunn devoted an epistolary poem in verse to the naval war in The Donkey's Ears: Politovsky's Letters Home (2000).

Two other English-language stories begin with the action at Port Arthur and follow the events thereafter: A Soldier of Japan: a tale of the Russo-Japanese War by Captain Frederick Sadleir Brereton, and The North Pacific[170] by Willis Boyd Allen (1855–1938).

Two more also involve young men fighting in the Japanese navy: Americans in For the Mikado[171] by Kirk Munroe, and a temporarily disgraced English officer in Under the Ensign of the Rising Sun[172] by Harry Collingwood, the pen-name of William Joseph Cosens Lancaster (1851–1922), whose speciality was naval fiction.

It was not until the changed political climate under Soviet rule that he began writing his historical epic Tsushima, based on his own experiences on board the battleship Oryol as well as on testimonies of fellow sailors and government archives.