Authorship of the Pauline epistles

There is strong consensus in modern New Testament scholarship on a core group of authentic Pauline epistles whose authorship is rarely contested: Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Philippians, 1 Thessalonians, and Philemon.

External evidence consists of references, again either explicit or implicit, to the text, especially during earliest times by those who had access to reliable sources now lost.

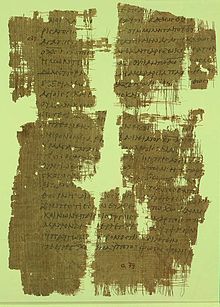

Examples include a list of accepted biblical books, such as the Muratorian fragment, or the contents of an early manuscript, such as Papyrus 46.

For example, the Second Epistle to the Thessalonians is named by Irenaeus in the mid-2nd century, as well as by Justin Martyr and Ignatius of Antioch; it is considered unlikely for the surviving version of this letter to have been written after this time.

However, use of this line of reasoning is dangerous, because of the incompleteness of the historical record: many ancient texts are lost, damaged, have been revised or possibly contrived.

For example, W. Michaelis saw the Christological likeness between the Pastoral Epistles and some of Paul's undisputed works, and argued in favor of Pauline authorship.

[14] G. Lohfink argued the theology of the Pastoral Epistles agreed with Paul's, but took this as proof someone wishing to enjoy the authority of an apostle copied the famous church leader.

[19] Nowadays, few scholars argue against this list of seven epistles, which all share common themes, emphasis, vocabulary and style.

W. Bujard attempted to show significant stylistic differences between Colossians and Paul's other works, such as unusual genitive constructions.

"[28] Whereas Paul, an apocalyptic Jew, anticipated the bodily resurrection of the faithful in the future (Rom 6:4-5), Colossians indicates that believers have already been raised with Christ (2:12; 3:1).

Similarly, though Paul envisions Christ's triumph over rulers and authorities as a future event (1 Cor 15:24), Colossians 2:15 acknowledges this as having already occurred.

[30] Kiley notes that while every one of Paul's main letters wish for financial report, Colossians is mysteriously lacking such a request.

The authenticity of this letter was first disputed by the Dutch Renaissance scholar Desiderius Erasmus, and in more recent times has drawn detailed criticism.

Also, the eschatological tone is more subdued than in other letters: the expectation of Christ's imminent return is unmentioned, while future generations are (3:21), as is a concern for social order.

[42] Donald Guthrie summarized the implications of this: "Advocates of non-Pauline authorship find it difficult to conceive that one mind could have produced two works possessing so remarkable a degree of similarity in theme and phraseology and yet differing in so many other respects, whereas advocates of Pauline authorship are equally emphatic that two minds could not have produced two such works with so much subtle interdependence blended with independence.

The epistle was included in the Marcion canon and the Muratorian fragment; it was mentioned by name by Irenaeus, and quoted by Ignatius, Justin, and Polycarp.

Udo Schnelle argued that 2 Thessalonians was significantly different in style from the undisputed epistles, characterizing it as whole and narrow, rather than as a lively and abrupt discussion on a range of issues.

Moreover, Alfred Loisy argued that it reflected knowledge of the synoptic gospels, which, according to the current scholarly consensus, had not been written when Paul wrote his epistles.

Bart D. Ehrman viewed the insistence of genuineness within the letter and the strong condemnation of forgery at its start as ploys commonly used by forgers.

Norman Perrin claimed that, in the time of Paul, prayer usually treated God the Father as ultimate judge, rather than Jesus.

Modern scholars postulate that the Pauline Epistles originally circulated in three forms, for example, from The Canon Debate,[58] attributed to Harry Y.

Gamble: Beginning in the early 19th century, many German biblical scholars began to question the traditional attribution of these letters to Paul.

[62] Robinson argued against this analysis,[63] while others have debated whether this should be grounds for rejection of Pauline authorship, as Acts concludes while Paul is still alive.

The pastoral epistles lay out church organization concerning the character and requirements for bishops, elders, deacons, and widows.

Moreover, scholars such as Robert Grant[68] have noted the many obvious differences in language and style between Hebrews and the correspondence explicitly ascribed to Paul.

Church Fathers and ante-Nicene writers such as Tertullian noted the different manner in which the theology and doctrine of the epistle appear.

But again, on the other hand, that the thoughts of the epistle are admirable, and not inferior to the acknowledged writings of the apostle, to this also everyone will consent as true who has given attention to reading the apostle….

Donald Guthrie, in his New Testament Introduction (1976), commented that "most modern writers find more difficulty in imagining how this Epistle was ever attributed to Paul than in disposing of the theory.

[80] Clement of Alexandria (c. 150-215 AD) quotes all the books of the New Testament with the exception of Philemon, James, 2 Peter, and 2 and 3 John.

[81] The earliest extant canon containing Paul's letters is from the 2nd century: In the nineteenth century, a group of scholars at the University of Tübingen, led by Ferdinand Christian Baur, engaged in radical bible study, including the claim that only Romans, 1 and 2 Corinthians, and Galatians were authored by Paul (i.e.