Autostereogram

Individuals with disordered binocular vision and who cannot perceive depth may require a wiggle stereogram to achieve a similar effect.

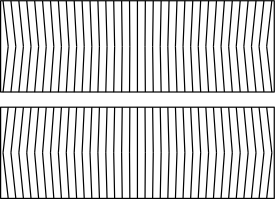

The simplest type of autostereogram consists of a horizontally repeating pattern, with small changes throughout, that looks like wallpaper.

When viewed with the proper vergence, an autostereogram does the same, the binocular disparity existing in adjacent parts of the repeating 2D patterns.

He supported his explanation by showing flat, two-dimensional pictures with such horizontal differences, stereograms, separately to the left and right eyes through a stereoscope he invented based on mirrors.

[3] In 1939 Boris Kompaneysky[7] published the first random-dot stereogram containing a hand-drawn image of the face of Venus,[8] intended to be viewed with a device.

In 1959, Bela Julesz,[9][10] vision scientist, psychologist, and MacArthur Fellow, invented random dot stereograms while working at Bell Laboratories on recognizing camouflaged objects from aerial pictures taken by spy planes.

The contours of the depth object become visible only after stereopsis had processed the differences in the horizontal positions of dots in the two eyes' images.

[13] Having experience with stereo imaging in holography, lenticular photography, and vectography, he developed a random-dot method based on closely spaced vertical lines in parallax.

[14] In 1979, Christopher Tyler of Smith-Kettlewell Institute, a student of Julesz and a visual psychophysicist, combined the theories behind single-image wallpaper stereograms and random-dot stereograms (the work of Julesz and Schilling) to create the first black-and-white random-dot autostereogram with the assistance of computer programmer Maureen Clarke using Apple II and BASIC.

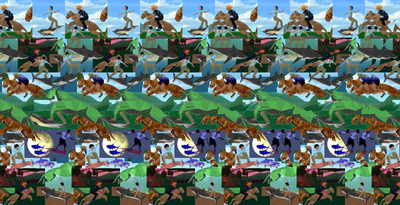

[16] This type of autostereogram allows a person to see 3D shapes from a single 2D image without the aid of optical equipment.

[17][18] In 1991 computer programmer Tom Baccei and artist Cheri Smith created the first color random-dot autostereograms, later marketed as Magic Eye.

[19] A computer procedure that extracts back the hidden geometry out of an autostereogram image was described by Ron Kimmel.

Since then several books were published with Magic Eye Beyond 3D: Improve Your Vision being one key publication that placed this intriguing illusion into the mainstream.

With the typical wall-eyed viewing, this gives the illusion of a plane bearing the same pattern but located behind the real wall.

[neutrality is disputed] Autostereograms where patterns in a particular row are repeated horizontally with the same spacing can be read either cross-eyed or wall-eyed.

The program tiles the pattern image horizontally to cover an area whose size is identical to the depth map.

If all autostereograms in the animation are produced using the same background pattern, it is often possible to see faint outlines of parts of the moving 3D object in the 2D autostereogram image without wall-eyed viewing; the constantly shifting pixels of the moving object can be clearly distinguished from the static background plane.

To eliminate this side effect, animated autostereograms often use shifting background in order to disguise the moving parts.

These are caused by the sideways shifts in the image due to small changes in the deflection sensitivity (linearity) of the line scan, which then become interpreted as depth.

This effect is especially apparent at the left hand edge of the screen where the scan speed is still settling after the flyback phase.

Because autostereograms are constructed based on stereo vision, persons with a variety of visual impairments, even those affecting only one eye, are unable to see the three-dimensional images.

For objects relatively close to the eyes, binocular vision plays an important role in depth perception.

Binocular vision allows the brain to create a single Cyclopean image and to attach a depth level to each point in it.

Stereo-vision based on parallax allows the brain to calculate depths of objects relative to the point of convergence.

If one has two eyes, fairly healthy eyesight, and no neurological conditions which prevent the perception of depth, then one is capable of learning to see the images within autostereograms.

Although the lens adjusts reflexively in order to produce clear, focused images, voluntary control over this process is possible.

[27] The viewer alternates instead between converging and diverging the two eyes, in the process seeing "double images" typically seen when one is drunk or otherwise intoxicated.

Eventually the brain will successfully match a pair of patterns reported by the two eyes and lock onto this particular degree of convergence.

It may help to establish proper convergence first by staring at either the top or the bottom of the autostereogram, where patterns are usually repeated at a constant interval.

If one slowly pulls back the picture away from the face, while refraining from focusing or rotating eyes, at some point the brain will lock onto a pair of patterns when the distance between them matches the current convergence degree of the two eyeballs.

) (

)

) (

)

)

or wall-

(

)

or wall-

(

)

eyed vergence.

)

eyed vergence.

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

Click here for the 800 × 400 version

)

Click here for the 800 × 400 version

)

)

)

)

)

)

)

)