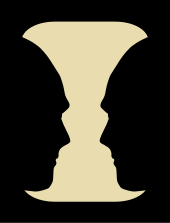

Rubin vase

Another example of a bistable figure Rubin included in his Danish-language, two-volume book was the Maltese cross.

The visual effect generally presents the viewer with two shape interpretations, each of which is consistent with the retinal image, but only one of which can be maintained at a given moment.

These types of stimuli are both interesting and useful because they provide an excellent and intuitive demonstration of the figure–ground distinction the brain makes during visual perception.

Rubin's figure–ground distinction, since it involved higher-level cognitive pattern matching, in which the overall picture determines its mental interpretation, rather than the net effect of the individual pieces, influenced the Gestalt psychologists, who discovered many similar percepts themselves.

[3] However, when the contours are not so unequal, ambiguity starts to creep into the previously simple inequality, and the brain must begin "shaping" what it sees; it can be shown that this shaping overrides and is at a higher level than feature recognition processes that pull together the face and the vase images – one can think of the lower levels putting together distinct regions of the picture (each region of which makes sense in isolation), but when the brain tries to make sense of it as a whole, contradictions ensue, and patterns must be discarded.