Molecular gastronomy

It is a branch of food science that approaches the preparation and enjoyment of nutrition from the perspective of a scientist at the scale of atoms, molecules, and mixtures.

Eventually, the shortened term "molecular gastronomy" became the name of the approach, based on exploring the science behind traditional cooking methods.

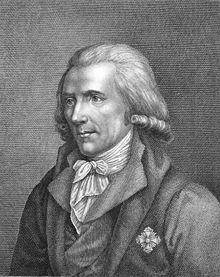

[11][12] The concept of molecular gastronomy was perhaps presaged by Marie-Antoine Carême, one of the most famous French chefs, who said in the early 19th century that when making a food stock "the broth must come to a boil very slowly, otherwise the albumin coagulates, hardens; the water, not having time to penetrate the meat, prevents the gelatinous part of the osmazome from detaching itself."

French writer Raymond Roussel, in his 1914 story "L'Allée aux lucioles" ("The Alley of Fireflies"), introduces a fictionalized version of French chemist Antoine de Lavoisier who, in the story, creates an apparently edible semi-permeable coating ("invol ...") that he uses to encase a tiny frozen sculpture made from one type of wine, which is immersed in another type of wine.

At a length of over 600 pages with section titles such as "The Relation Of Cookery To Colloidal Chemistry", "Coagulation Of Proteins", "The Factors Affecting The Viscosity Of Cream And Ice Cream", "Syneresis", "Hydrolysis Of Collagen" and "Changes In Cooked Meat And The Cooking Of Meat", the volume rivals or exceeds the scope of many other books on the subject, at a much earlier date.

[18] That same year, he held a presentation for the Royal Society of London (also entitled "The Physicist in the Kitchen") in which he stated:[19] I think it is a sad reflection on our civilization that while we can and do measure the temperature in the atmosphere of Venus we do not know what goes on inside our soufflés.Kurti demonstrated making meringue in a vacuum chamber, the cooking of sausages by connecting them across a car battery, the digestion of protein by fresh pineapple juice, and a reverse baked alaska—hot inside, cold outside—cooked in a microwave oven.

[19][20] Kurti was also an advocate of low temperature cooking, repeating 18th century experiments by British scientist Benjamin Thompson by leaving a 2 kg (4.4 lb) lamb joint in an oven at 80 °C (176 °F).

He served as an adviser to the French minister of education, lectured internationally, and was invited to join the lab of Nobel-winning molecular chemist Jean-Marie Lehn.

[23][24][25] The objectives of molecular gastronomy, as defined by Hervé This, are seeking for the mechanisms of culinary transformations and processes (from a chemical and physical point of view) in three areas:[8][26] The original fundamental objectives of molecular gastronomy were defined by This in his doctoral dissertation as:[26] Hervé This later recognized points 3, 4, and 5 as being not entirely scientific endeavors (more application of technology and educational), and has revised the list.

[11] Prime topics for study include[27] In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the term started to be used to describe a new style of cooking in which some chefs began to explore new possibilities in the kitchen by embracing science, research, technological advances in equipment and various natural gums and hydrocolloids produced by the commercial food processing industry.

[32] Chefs who are often associated with molecular gastronomy because of their embrace of science include Heston Blumenthal, Grant Achatz, Ferran Adrià, José Andrés, Marcel Vigneron, Homaro Cantu, Michael Carlson, Wylie Dufresne, and Adam Melonas.