Aviation in the pioneer era

Flying displays such as the Grande Semaine d'Aviation of 1909 and air races such as the Gordon Bennett Trophy and the Circuit of Europe attracted huge audiences and successful pilots such as Jules Védrines and Claude Grahame-White became celebrities.

After their flights in 1905 the Wrights stopped work on developing their aircraft and concentrated on trying to commercially exploit their invention, attempting to interest the military authorities of the United States and then, after being rebuffed, France and Great Britain.

To publicize the aeronautical concourse at the upcoming World's Fair in St. Louis, Octave Chanute gave a number of lectures at aero-clubs in Europe, sharing his excitement about flying gliders.

You, the Maecenases; and you too, the Government; put your hands in your pockets–;or else we are beaten!In October 1904 the Aéro-Club de France announced a series of prizes for achievements in powered flight, but little practical work was done: Ferdinand Ferber, an army officer who in 1898 had experimented with a hang-glider based on that of Otto Lilienthal continued his work without any notable success, Archdeacon commissioned the construction of a glider based on the Wright design but smaller and lacking the provision for roll control which made a number of brief flights at Berck-sur-Mer in April 1904, piloted by Ferber and Gabriel Voisin (the longest of around 29 m (95 ft), compared to the 190 m (620 ft) achieved by the Wrights in 1902):[3] another glider based on the Wright design was constructed by Robert Esnault-Pelterie, who rejected wing-warping as unsafe and instead fitted a pair of mid-gap control surfaces in front of the wings, intended to be used in a differential manner in place of wing-warping and in conjunction to act as elevators (as what are known today as elevons): this is the first recorded use of ailerons, the concept for which had been patented over a generation earlier by M. P. W. Boulton of the United Kingdom in 1868.

Ferber's copy was likewise unsuccessful: it was crudely constructed, without ribs to maintain the wing camber, but is notable for his later addition of a fixed rear-mounted stabilising tail surface, the first instance of this feature in a full-size aircraft.

Full details of the Wright Brothers' flight control system was published in l'Aérophile in the January 1906 issue,[6] making clear both the mechanism and its aerodynamic reason.

[7] and in February 1908 a second example flown by Henri Farman won the Archdeacon-de la Meurthe Grand Prix d'Aviation for the first officially observed closed-circuit flight of over a kilometer.

The AEA produced a number of fundamentally similar biplane designs, greatly influenced by the Wright's work, and these were flown with increasing success during 1908.

On 4 July 1908 their next aircraft, the June Bug piloted by Glenn Curtiss, won the Scientific American trophy for the first officially observed one kilometer flight in North America.

The Aéro-Club de France issued its first pilot's licences in January, awarding them to a select few pioneer aviators including the Wright Brothers.

The year also saw the Grande Semaine d'Aviation de la Champagne at Rheims, attended by half a million people, including Armand Fallières, the President of France; the King of Belgium and senior British political figures including David Lloyd George, who afterwards commented "Flying machines are no longer toys and dreams; they are an established fact"[12] A second aircraft exhibition held in October at the Grand Palais in Paris attracted 100,000 visitors.

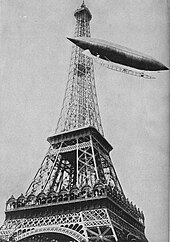

Alberto Santos Dumont achieved celebrity status on 19 October 1901 by winning a prize for making a flight from Parc Saint Cloud to the Eiffel Tower and back.

In Germany Graf (Count) Ferdinand von Zeppelin pioneered the construction of large rigid airships: his first design of 1900–01 had only limited success and his second was not constructed until 1906, but his efforts became an enormous source of patriotic pride for the German people: so much so that when his fourth airship LZ 4 was wrecked in a storm a public collection raised more than six million marks to enable him to carry on his work.

Using Zeppelins, the world's first airline, DELAG, was established in Germany in 1910, operating pleasure cruises rather than a scheduled transport service: by the outbreak of war in 1914 1588 flights had been made carrying 10,197 fare-paying passengers.

[14] The military threat posed by these large airships, greatly superior in carrying power and endurance to heavier-than air machines of the time, caused considerable concern in other countries, especially Britain.

In Great Britain Frederick Handley Page established an aircraft business in 1909 but was largely reliant on selling components such as connecting sockets and wire-strainers to other enthusiasts, while the Short Brothers, who had started in business manufacturing balloons, had transferred their interests to heavier-than air aviation and started licence production of the Wright design as well as working on their own designs.

The first competition, held in 1909 during the Grande Semaine d'Aviation at Reims, was over a distance of 20 km (12 mi) and was won by Glenn Curtiss at a speed of 75.27 km/h (46.77 mph).

All the competing aircraft with the exception of the Voisin biplanes had roll control, using either ailerons or wing-warping[21] The Wright design differed from the others in having no rear-mounted horizontal stabilising surface.

They used a single flight[clarification needed] engine, a 12 hp water-cooled four-cylinder inline type with five main bearings and fuel injection.

The Antoinette 8V incorporated manifold fuel injection, evaporative water cooling and other advanced features, weighed 95 kg (209 lb) and produced 37 kW (50 hp).

The air-cooled Anzani 3-cylinder semi-radial or fan engine of 1909 (also built in a true, 120° cylinder angle radial form) developed only 25 hp (19 kW) but was much lighter than the liquid-cooled Antoinette, and was chosen by Louis Blériot for his cross-Channel flight.

A major advance came with the introduction of the Seguin brothers' Gnome Omega seven-cylinder, air-cooled rotary engine, exhibited at the Paris Aero Salon 1n 1908 and first fitted to an aircraft in 1909.

[28] In 1909 Henri Deutsch de la Meurthe endowed a department devoted to aeronautics at the University of Paris[29] In France the famous engineer Gustave Eiffel performed a series of experiments to investigate the effects of wind resistance on moving bodies by dropping test apparatus down a wire suspended from the Eiffel Tower: he later built a wind tunnel at the base of the Tower, in which models of many pioneer French aircraft were tested and carried out pioneering work on aerofoil sections.

Pilot training was rudimentary: although the Wright Model A used by the Wright Brothers for training in Europe had been fitted with dual control,[30] dual-control aircraft were not generally used, and aspiring pilots would often simply be put in charge of a machine and encouraged to progress from taxying the aircraft then short straight line flights to flights involving turns.

Most flight training was done early in the morning or in the evening when winds tend to be low, and the time taken to qualify for a licence was greatly dependent on the weather.

In 1910 Louis Paulhan and Claude Grahame-White competed to win the Daily Mail prize for a flight between London and Manchester, attracting Major long-distance aeroplane races, such as the Circuit of Europe and the Aerial Derby began in 1911 - and also attracted enormous crowds; while in the same year in the United States, a suburb of Chicago, Illinois had an important aerodrome-format aviation site dedicated in Cicero, IL that operated for several years[32] before its closure and relocation in 1916.

Many military traditionalists refused to regard aeroplanes as more than toys, but these were counterbalanced by advocates of the new technology, and both the US and the major European nations had established heavier-than-air aviation arms by the end of 1911.

In October 1908 Samuel Cody had flown the British Army Aeroplane No.1 for a distance of 424 m (1,391 ft) and J. W. Dunne had made a number of successful gliding experiments, performed in great secrecy at Blair Atholl in Scotland, but in 1909 the British War office had stopped all official funding of heavier-than-air aviation, preferring to spend its money on airships.

Aeronautical Division, U.S. Signal Corps The American military pioneered naval aviation, with the first take-off from a ship being made on 14 November 1910 by Eugene Ely using a Curtiss biplane flown from a temporary platform erected over the bow of the light cruiser USS Birmingham.

The earliest recorded use of explosive ordnance of any type from an aircraft occurred on November 1, 1911, when Italian pilot Giulio Gavotti dropped several, grapefruit-sized cipelli grenades on Ottoman positions in Libya – Gavotti's raid caused no casualties, functionally only resulting in the earliest known case of air-delivered harassing fire—but marked the first known use of an aircraft for military combat purposes.