Aztec sun stone

[6] There are no clear indications about the authorship or purpose of the monolith, although there are certain references to the construction of a huge block of stone by the Mexicas in their last stage of splendor.

[7] Juan de Torquemada described in his Monarquía indiana how Moctezuma Xocoyotzin ordered to bring a large rock from Tenanitla, today San Ángel, to Tenochtitlan, but on the way it fell on the bridge of the Xoloco neighborhood.

[9] After the conquest, it was transferred to the exterior of the Templo Mayor, to the west of the then Palacio Virreinal and the Acequia Real, where it remained uncovered, with the relief upwards for many years.

[8] According to Durán, Alonso de Montúfar, Archbishop of Mexico from 1551 to 1572, ordered the burial of the Sun Stone so that "the memory of the ancient sacrifice that was made there would be lost".

[8] Towards the end of the 18th century, the viceroy Juan Vicente de Güemes initiated a series of urban reforms in the capital of New Spain.

It was José Damián Ortiz de Castro, the architect overseeing public works, who reported the finding of the sun stone on 17 December 1790.

The monolith was found half a yard (about 40 centimeters) under the ground surface and 60 meters to the west of the second door of the viceregal palace,[8] and removed from the earth with a "real rigging with double pulley".

León y Gama said the following: ... On the occasion of the new paving, the floor of the Plaza being lowered, on December 17 of the same year, 1790, it was discovered only half a yard deep, and at a distance of 80 to the West from the same second door of the Royal Palace, and 37 north of the Portal of Flowers, the second Stone, by the back surface of it.León y Gama himself interceded before the canon of the cathedral in order that the monolith found would not be buried again due to its perceived pagan origin (for which it had been buried almost two centuries before).

[8] Mexican sources alleged that during the Mexican–American War, soldiers of the United States Army who occupied the plaza used it for target shooting, though there is no evidence of such damage to the sculpture.

[8] Victorious General Winfield Scott contemplated taking it back to Washington D.C. as a war trophy, if the Mexicans did not make peace.

[12] In August 1885, the stone was transferred to the Monolith Gallery of the Archaeological Museum on Moneda Street, on the initiative of Jesús Sánchez, director of the same.

The state-sponsored monument linked aspects of Aztec ideology such as the importance of violence and warfare, the cosmic cycles, and the nature of the relationship between gods and man.

The Aztec elite used this relationship with the cosmos and the bloodshed often associated with it to maintain control over the population, and the sun stone was a tool in which the ideology was visually manifested.

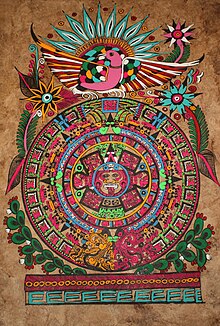

[13] In the center of the monolith is often believed to be the face of the solar deity, Tonatiuh,[14] which appears inside the glyph for "movement" (Nahuatl: Ōllin), the name of the current era.

Some scholars have argued that the identity of the central face is of the earth monster, Tlaltecuhtli, or of a hybrid deity known as "Yohualtecuhtli" who is referred to as the "Lord of the Night".

[15] The central figure is shown holding a human heart in each of his clawed hands, and his tongue is represented by a stone sacrificial knife (Tecpatl).

Placed among these four squares are three additional dates, "One Flint" (Tecpatl), "One Rain" (Atl), and "Seven Monkey" (Ozomahtli), and a Xiuhuitzolli, or ruler's turquoise diadem, glyph.

The monument is not a functioning calendar, but instead uses the calendrical glyphs to reference the cyclical concepts of time and its relationship to the cosmic conflicts within the Aztec ideology.

The order is as follows: 1. cipactli – crocodile, 2. ehécatl – wind, 3. calli – house, 4. cuetzpallin – lizard, 5. cóatl – serpent, 6. miquiztli – skull/death, 7. mázatl – deer, 8. tochtli – rabbit, 9. atl – water, 10. itzcuintli – dog, 11. ozomatli – monkey, 12. malinalli – herb, 13. ácatl – cane, 14. océlotl – jaguar, 15. cuauhtli – eagle, 16. cozcacuauhtli – vulture, 17. ollín – movement, 18. técpatl – flint, 19. quiahuitl – rain, 20. xóchitl – flower [19]The second concentric zone or ring contains several square sections, with each section containing five points.

This work was later to be expanded by Felipe Solís and other scholars who would re-examine the idea of coloring and create updated digitized images for a better understanding of what the stone might have looked like.

[19] It was generally established that the four symbols included in the Ollin glyph represent the four past suns that the Mexica believed the earth had passed through.

[21] Modern archaeologists, such as those at the National Anthropology Museum in Mexico City, believe it is more likely to have been used primarily as a ceremonial basin or ritual altar for gladiatorial sacrifices, than as an astrological or astronomical reference.

[26] Townsend argues for this idea, claiming that the small glyphs of additional dates amongst the four previous suns—1 Flint (Tecpatl), 1 Rain (Atl), and 7 Monkey (Ozomahtli)—represent matters of historical importance to the Mexica state.

As the Aztecs grew in power, the state needed to find ways to maintain order and control over the conquered peoples, and they used religion and violence to accomplish the task.

[31] The words and actions of the Spanish, such as the destruction, removal, or burial of Aztec objects like the Sun Stone supported this message of inferiority, which still has an impact today.

Although the object was being publicly honored, placing it in the shadow of a Catholic institution for nearly a century sent a message to some people that the Spanish would continue to dominate over the remnants of Aztec culture.

By referring to it as a "sculpture"[33] and by displaying it vertically on the wall instead of placed horizontally how it was originally used,[20] the monument is defined within the Western perspective and therefore loses its cultural significance.

The current display and discussion surrounding the Sun Stone is part of a greater debate on how to decolonize non-Western material culture.

[37][38] The sculpture, officially known as Aztec Calendar Stone in the museum catalog but called Altar of the Five Cosmogonic Eras,[35] bears similar hieroglyphic inscriptions around the central compass motif but is distinct in that it is a rectangular prism instead of cylindrical shape, allowing the artists to add the symbols of the four previous suns at the corners.

[35] Another object, the Ceremonial Seat of Fire which belongs to the Eusebio Davalos Hurtado Museum of Mexica Sculpture,[35] is visually similar but omits the central Ollin image in favor of the Sun.