Moctezuma II

His story remains one of the most well-known conquest narratives from the history of European contact with Native Americans, and he has been mentioned or portrayed in numerous works of historical fiction and popular culture.

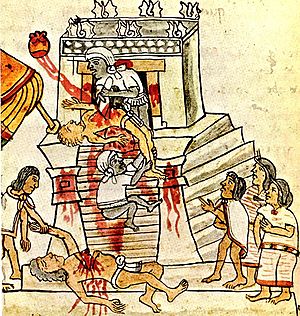

[9] His name glyph, shown in the upper left corner of the image from the Codex Mendoza below, was composed of a diadem (xiuhuitzolli) on straight hair with an attached earspool, a separate nosepiece, and a speech scroll.

[25] The drought and famine ultimately lasted three years,[26] and at some point became so severe that some noblemen reportedly sold their children as slaves in exchange for food to avoid starvation.

Some provinces, however, ended up paying more tribute permanently, most likely as the result of his primary military focus shifting from territorial expansion to stabilization of the empire through the suppression of rebellions.

For example, the province of Amaquemecan, which formed part of the Chalco region, was assigned to pay an additional tribute of stone and wood twice or thrice a year for Tenochtitlan's building projects.

As mentioned previously, the first campaign during his reign, which was done in honor of his coronation, was the suppression of a rebellion in Nopallan (today known as Santos Reyes Nopala) and Icpatepec (a Mixtec town that no longer exists which was near Silacayoapam), both in modern-day Oaxaca.

[59] The conquest of Tototepec formed part of the conquests of some of the last few Tlapanec territories of modern-day Guerrero, an area which had already been in decline since Moctezuma I began his first campaigns in the region and probably turned the Kingdom of Tlachinollan (modern-day Tlapa) into a tributary province during the rule of Lord Tlaloc between 1461 and 1467 (though the kingdom would not be invaded and fully conquered until the reign of Ahuizotl in 1486, along with Caltitlan, a city neighboring west of Tlapa).

[63] Several military defeats occurred in some of these expansionist campaigns, however, such as the invasion of Amatlan in 1509, where an unexpected series of snowstorms and blizzards killed many soldiers, making the surviving ones too low in numbers to fight.

[66] Among the final military campaigns carried out by Moctezuma, aside from the late stages of the war against Tlaxcala, were the conquests of Mazatzintlan and Zacatepec, which formed part of the Chichimec region.

According to Alva Ixtlilxóchitl, the issue began when Moctezuma sent an embassy to Nezahualpilli reprimanding him for not sacrificing any Tlaxcalan prisoners since the last 4 years, during the war with Tlaxcala (see below), threatening him saying that he was angering the gods.

[70] His death is recorded to have been mourned in Texcoco, Tenochtitlan, Tlacopan, and even Chalco and Xochimilco, as all of these altepeme gave precious offerings, like jewelry and clothes, and sacrifices in his honor.

In the meantime, the brothers agreed to try to reach a consensus through a peaceful debate, as Ixtlilxochitl did not want to fight either, as he claimed that he only sent the troops as a means of protest and not to wage war.

The Tlaxcalans became greatly worried about this and began to grow suspicious of all allies they had fearing a betrayal, as Huejotzingo was one of Tlaxcala's closest states, as proven by its support at the battle of Atlixco.

The Huexotzinca became greatly worried and knew they couldn't win the war alone, therefore a prince named Teayehuatl decided to send an embassy to Mexico to request aid against the Tlaxcalans.

The battle lasted 20 days, and both armies suffered huge losses, as the Tlaxcalans had a famous general captured and the Mexica lost so many men that they requested emergency reinforcements, asking for "all kinds of people in the shortest possible time".

In his Historia, Bernal Díaz del Castillo states that on 29 June 1520, the Spanish forced Moctezuma to appear on the balcony of his palace, appealing to his countrymen to retreat.

Díaz states: "Many of the Mexican Chieftains and Captains knew him well and at once ordered their people to be silent and not to discharge darts, stones or arrows, and four of them reached a spot where Montezuma [Moctezuma] could speak to them.

And four days after they had been hurled from the [pyramid] temple, [the Spaniards] came to cast away [the bodies of] Moctezuma and Itzquauhtzin, who had died, at the water's edge at a place called Teoayoc.

The firsthand account of Bernal Díaz del Castillo's True History of the Conquest of New Spain paints a portrait of a noble leader who struggles to maintain order in his kingdom after he is taken prisoner by Hernán Cortés.

In his first description of Moctezuma, Díaz del Castillo writes: The Great Montezuma was about forty years old, of good height, well proportioned, spare and slight, and not very dark, though of the usual Indian complexion.

[121]When Moctezuma was allegedly killed by being stoned to death by his people, "Cortés and all of us captains and soldiers wept for him, and there was no one among us that knew him and had dealings with him who did not mourn him as if he were our father, which was not surprising since he was so good.

"[122] Unlike Bernal Díaz, who was recording his memories many years after the fact, Cortés wrote his Cartas de relación (Letters from Mexico) to justify his actions to the Spanish Crown.

[123]Anthony Pagden and Eulalia Guzmán have pointed out the Biblical messages that Cortés seems to ascribe to Moctezuma's retelling of the legend of Quetzalcoatl as a vengeful Messiah who would return to rule over the Mexica.

Rebecca Dufendach argues that the Codex reflects the native informants' uniquely indigenous manner of portraying leaders who suffered from poor health brought on by fright.

[130] Other parties have also propagated the idea that the Native Americans believed the conquistadors to be gods, most notably the historians of the Franciscan order such as Fray Gerónimo de Mendieta.

This warning caused Moctezuma great fear and he made a series of erratic decisions immediately after, such as severe punishments against his soldiers for disappointing results after battles against the Tlaxcalans.

[citation needed] Moctezuma had numerous wives and concubines by whom he fathered an enormous family, but only two women held the position of queen – Tlapalizquixochtzin and Teotlalco.

[139] Among the sports he practised, he was an active hunter, and often used to hunt for deer, rabbits, and various birds in a certain section of a forest (likely the Bosque de Chapultepec) that was exclusive to him and whomever he invited.

[52] A Spanish soldier accompanying Hernan Cortés during the conquest of the Aztec Empire reported that when Moctezuma II dined, he took no other beverage than chocolate, served in a golden goblet.

[154] Notable descendants from this line include Mexican politicians and philanthropists, Secretary Gerardo Ruiz de Esparza and Luis Rubén (né Valadez Bourbon) of the influential Macias-Valadez in the state of Jalisco, Mexico.