Rayleigh–Bénard convection

This equilibrium is also asymptotically stable: after a local, temporary perturbation of the outside temperature, it will go back to its uniform state, in line with the second law of thermodynamics).

Then, the temperature of the bottom plane is increased slightly yielding a flow of thermal energy conducted through the liquid.

The system will begin to have a structure of thermal conductivity: the temperature, and the density and pressure with it, will vary linearly between the bottom and top plane.

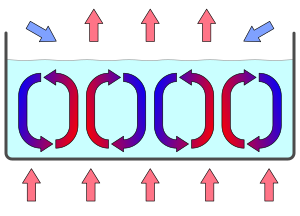

Once conduction is established, the microscopic random movement spontaneously becomes ordered on a macroscopic level, forming Benard convection cells, with a characteristic correlation length.

The rotation of the cells is stable and will alternate from clock-wise to counter-clockwise horizontally; this is an example of spontaneous symmetry breaking.

This inability to predict long-range conditions and sensitivity to initial-conditions are characteristics of chaotic or complex systems (i.e., the butterfly effect).

If the temperature of the bottom plane was to be further increased, the structure would become more complex in space and time; the turbulent flow would become chaotic.

Convective Bénard cells tend to approximate regular right hexagonal prisms, particularly in the absence of turbulence,[10][11][12] although certain experimental conditions can result in the formation of regular right square prisms[13] or spirals.

In general the solutions to the Rayleigh and Pearson[15] analysis (linear theory) assuming an infinite horizontal layer gives rise to degeneracy meaning that many patterns may be obtained by the system.

[16] The simplest case is that of two free boundaries, which Lord Rayleigh solved in 1916, obtaining Ra = 27⁄4 π4 ≈ 657.51.

In 1870, the Irish-Scottish physicist and engineer James Thomson (1822–1892), elder brother of Lord Kelvin, observed water cooling in a tub; he noted that the soapy film on the water's surface was divided as if the surface had been tiled (tesselated).

[21] This pattern of convection, whose effects are due solely to a temperature gradient, was first successfully analyzed in 1916 by Lord Rayleigh.