Viscosity

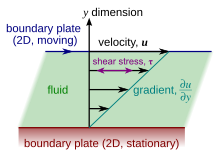

In the Couette flow, a fluid is trapped between two infinitely large plates, one fixed and one in parallel motion at constant speed

[7] Each layer of fluid moves faster than the one just below it, and friction between them gives rise to a force resisting their relative motion.

A potential issue is that viscosity depends, in principle, on the full microscopic state of the fluid, which encompasses the positions and momenta of every particle in the system.

[16][17] Nevertheless, viscosity may still carry a non-negligible dependence on several system properties, such as temperature, pressure, and the amplitude and frequency of any external forcing.

[20] The fact that mass, momentum, and energy (heat) transport are among the most relevant processes in continuum mechanics is not a coincidence: these are among the few physical quantities that are conserved at the microscopic level in interparticle collisions.

A magnetorheological fluid, for example, becomes thicker when subjected to a magnetic field, possibly to the point of behaving like a solid.

Conversely, many "solids" (even granite) will flow like liquids, albeit very slowly, even under arbitrarily small stress.

Close temperature control of the fluid is essential to obtain accurate measurements, particularly in materials like lubricants, whose viscosity can double with a change of only 5 °C.

A rheometer is used for fluids that cannot be defined by a single value of viscosity and therefore require more parameters to be set and measured than is the case for a viscometer.

Apparent viscosity is a calculation derived from tests performed on drilling fluid used in oil or gas well development.

The most frequently used systems of US customary, or Imperial, units are the British Gravitational (BG) and English Engineering (EE).

Momentum transport in gases is mediated by discrete molecular collisions, and in liquids by attractive forces that bind molecules close together.

More fundamentally, the notion of a mean free path becomes imprecise for particles that interact over a finite range, which limits the usefulness of the concept for describing real-world gases.

A simple example is the Sutherland model,[a] which describes rigid elastic spheres with weak mutual attraction.

Due to random thermal motion, a molecule "hops" between cages at a rate which varies inversely with the strength of molecular attractions.

[46] It has also been argued that the exponential dependence in equation (1) does not necessarily describe experimental observations more accurately than simpler, non-exponential expressions.

Foregoing simplicity in favor of precision, it is possible to write rigorous expressions for viscosity starting from the fundamental equations of motion for molecules.

For gas mixtures consisting of simple molecules, Revised Enskog Theory has been shown to accurately represent both the density- and temperature dependence of the viscosity over a wide range of conditions.

Estimated values of these constants are shown below for sodium chloride and potassium iodide at temperature 25 °C (mol = mole, L = liter).

can be defined in terms of stress and strain components which are averaged over a volume large compared with the distance between the suspended particles, but small with respect to macroscopic dimensions.

The presence of internal circulation can decrease the observed effective viscosity, and different theoretical or semi-empirical models must be used.

[68][69] Upon specifying the temperature dependence of the shear modulus via thermal expansion and via the repulsive part of the intermolecular potential, another two-exponential equation is retrieved:[70] where

is a parameter which measures the steepness of the power-law rise of the ascending flank of the first peak of the radial distribution function, and is quantitatively related to the repulsive part of the interatomic potential.

[73][74] Because viscosity depends continuously on temperature and pressure, it cannot be fully characterized by a finite number of experimental measurements.

If such an expression is fit to high-fidelity data over a large range of temperatures and pressures, then it is called a "reference correlation" for that fluid.

Reference correlations have been published for many pure fluids; a few examples are water, carbon dioxide, ammonia, benzene, and xenon.

Thermophysical modeling software often relies on reference correlations for predicting viscosity at user-specified temperature and pressure.

These formulas include the Green–Kubo relations for the linear shear viscosity and the transient time correlation function expressions derived by Evans and Morriss in 1988.

The disadvantage is that they require detailed knowledge of particle trajectories, available only in computationally expensive simulations such as molecular dynamics.

The values listed are representative estimates only, as they do not account for measurement uncertainties, variability in material definitions, or non-Newtonian behavior.