Bacterial cellulose

While cellulose is a basic structural material of most plants, it is also produced by bacteria, principally of the genera Komagataeibacter, Acetobacter, Sarcina ventriculi and Agrobacterium.

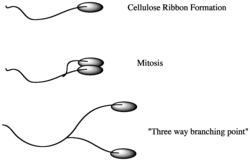

[1] In natural habitats, the majority of bacteria synthesize extracellular polysaccharides, such as cellulose, which form protective envelopes around the cells.

For example, attention has been given to the bacteria Komagataeibacter xylinus due to its cellulose's unique mechanical properties and applications to biotechnology, microbiology, and materials science.

Browne studied the cellulose material obtained by fermentation of Louisiana sugar cane juice and affirmed the results by A.J.

In 1931, Tarr and Hibbert published the first detailed study of the formation of bacterial cellulose by conducting a series of experiments to grow A. xylinum on culture mediums.

Of these, A. xylinum is the model microorganism for basic and applied studies on cellulose due to its ability to produce relatively high levels of polymer from a wide range of carbon and nitrogen sources.

[24] In reactors where the process is more complex, water-soluble polysaccharides such as agar,[25] acetan, and sodium alginate[26] are added to prevent clumping or coagulation of bacterial cellulose.

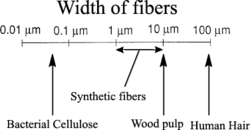

[8] In general, microbial cellulose is more chemically pure, containing no hemicellulose or lignin, has a higher water holding capacity and hydrophilicity, greater tensile strength resulting from a larger amount of polymerization, ultrafine network architecture.

Furthermore, bacterial cellulose can be produced on a variety of substrates and can be grown to virtually any shape due to the high moldability during formation.

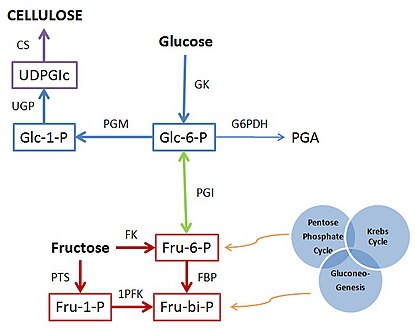

[9] Cellulose is composed of carbon, oxygen, and hydrogen, and is classified as a polysaccharide, indicating it is a carbohydrate that exhibits polymeric characteristics.

The structural role of cellulose in cell walls has been likened to that of the glass strands of fiberglass or to the supporting rods within reinforced concrete.

[citation needed] Cellulose fibrils are highly insoluble and inelastic and, because of their molecular configuration, have a tensile strength comparable to that of steel.

[citation needed] Consequently, cellulose imparts a unique combination of chemical resilience and mechanical support and flexibility to the tissues in which it resides.

[36] Bacterial cellulose has been suggested to have a construction like a ‘cage' which protects the cell from foreign material and heavy-metal ions, while still allowing nutrients to be supplied easily by diffusion.

Cellulose has a high swollen fiber network resulting from the presence of pore structures and tunnels within the wet pellicle.

The sheet's high Young's modulus has been attributed to the unique super-molecular structure in which fibrils of biological origin are preserved and bound tightly by hydrogen bonds.

Two common crystalline forms of cellulose, designated as I and II, are distinguishable by X-ray, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), Raman spectroscopy, and infrared analysis.

In addition to the crystalline and amorphous regions, cellulose fibers contain various types of irregularities, such as kinks or twists of the microfibrils, or voids such as surface micropores, large pits, and capillaries.

[41] Bacterial cellulose pellicles were proposed as a temporary skin substitute in case of human burns and other dermal injuries.

[42] The oldest known use of bacterial cellulose is as the raw material of nata de piña, a traditional sweet candy dessert of the Philippines.

Several natural colored pigments (oxycarotenoids, anthocyanins and related antioxidants and free radical scavengers) were incorporated into bacterial cellulose cubes in order to render the dessert more attractive.

[35] Due to its high sonic velocity and low dynamic loss, bacterial cellulose has been used as an acoustic or filter membrane in hi-fidelity loudspeakers and headphones as marketed by the Sony Corporation.

Also, the microbial cellulose molds very well to the surface of the skin, providing a conformal covering even in usually difficult places to dress wounds, such as areas on the face.

[1] Another microbial cellulose commercial treatment product is XCell produced by the Xylos Corporation, which is mainly used to treat wounds from venous ulcers.

In addition to increasing the drying time and water holding abilities, liquid medicines were able to be absorbed by the microbial cellulose coated gauze, allowing them to work at the injury site.

Currently, plant cellulose is used to produce the bulk of traditional paper, but due to its low purity it must be mixed with other substances such as lignin.

However, due to microbial cellulose's higher purity and microfibril structure, it may prove to be an excellent candidate for an electronic paper substrate.

The bistable dyes change from clear to dark upon the application of the appropriate voltages, which when placed in a pixel structure, would allow images to be formed.

Further research has been done to apply bacterial cellulose as a substrate in electronic devices with the potential to be used as e-book tablets, e-newspapers, dynamic wall papers, rewritable maps and learning tools.

[35] Due to the inefficient production process, the current price of bacterial cellulose remains too high to make it commercially attractive and viable on a large scale.