Bai Juyi

[1] Bai was also influential in the historical development of Japanese literature, where he is better known by the on'yomi reading of his courtesy name, Haku Rakuten (shinjitai: 白楽天).

[3] Bai Juyi was born in 772[4] in Taiyuan, Shanxi, which was then a few miles from location of the modern city, although he was in Zhengyang, Henan for most of his childhood.

[5] At the age of ten he was sent away from his family to avoid a war that broke out in the north of China, and went to live with relatives in the area known as Jiangnan, more specifically Xuzhou.

He was made a member (scholar) of the Hanlin Academy, in 807, and Reminder of the Left from 807 until 815,[citation needed] except when in 811 his mother died, and he spent the traditional three-year mourning period again along the Wei River, before returning to court in the winter of 814, where he held the title of Assistant Secretary to the Prince's Tutor.

As Assistant Secretary to the Prince's Tutor, Bai's memorial was a breach of protocol — he should have waited for those of censorial authority to take the lead before offering his own criticism.

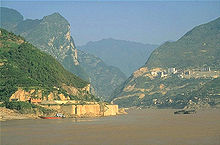

Bai Juyi was demoted to the rank of Sub-Prefect and banished from the court and the capital city to Jiujiang, then known as Xun Yang, on the southern shores of the Yangtze River in northwest Jiangxi Province.

This trip allowed Bai Juyi a few days to visit his friend Yuan Zhen, who was also in exile and with whom he explored the rock caves located at Yichang.

Again, Bai Juyi was sent away from the court and the capital, but this time to the important position of the thriving town of Hangzhou, which was at the southern terminus of the Grand Canal and located in the scenic neighborhood of West Lake.

Fortunately for their friendship, Yuan Zhen at the time was serving an assignment in nearby Ningbo, also in what is today Zhejiang, so the two could occasionally get together,[12] at least until Bai Juyi's term as Governor expired.

In 825, at age 53, Bai Juyi was given the position of Governor (Prefect) of Suzhou, situated on the lower reaches of the Yangtze River and on the shores of Lake Tai.

This area, now a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is famous for its tens of thousands of statues of Buddha and his disciples carved out of the rock.

[15] In 846, Bai Juyi died, leaving instructions for a simple burial in a grave at the monastery, with a plain style funeral, and to not have a posthumous title conferred upon him.

[4] One of the most prolific of the Tang poets, Bai Juyi wrote over 2,800 poems, which he had copied and distributed to ensure their survival.

The accessibility of Bai Juyi's poems made them extremely popular in his lifetime, in both China and Japan, and they continue to be read in these countries today.

Han's sovereign prized the beauty of flesh, he longed for such as ruins domains; For many years he ruled the Earth and sought for one in vain.

In springtime's chill he let her bathe in Huaqing Palace's pools Whose warm springs' glistening waters washed flecks of dried lotions away.

Tresses like cloud, face like a flower, gold pins that swayed to her steps; It was warm in the lotus-embroidered tents where they passed the nights of spring.

Like Du Fu, Bai had a strong sense of social responsibility and is well known for his satirical poems, such as The Elderly Charcoal Seller.

One friend, Yu Shunzhi, sent Bai a bolt of cloth as a gift from a far-off posting, and Bai Juyi debated on how best to use the precious material: About to cut it to make a mattress, pitying the breaking of the leaves; about to cut it to make a bag, pitying the dividing of the flowers.

[18] Bai's works were also highly renowned in Japan, and many of his poems were quoted and referenced in The Tale of Genji by Murasaki Shikibu.

As a government official and a litterateur, Bai observed the court music performance that was seriously affected by Xiyu (西域, Western regions), and he made some articles with indignation to criticize that phenomenon.

As an informal leader of a group of poets who rejected the courtly style of the time and emphasized the didactic function of literature, Bai believing that every literary work should contain a fitting moral and a well-defined social purpose.

Bai's another poem, Libuji (立部伎), translated as Standing Section Players, reflected the phenomenon of "decline in imperial court music".

The pipa in the poems of Bai Juyi represents the expression of love, the action of communicating, and especially the poet's feelings on listening to music.

[26] Bai Juyi is considered one of the greatest Chinese poets, but even during the ninth century, sharp divide in critical opinions of his poetry already existed.

In a tomb inscription for Li Kan (李戡), a critic of Bai, poet Du Mu wrote, couched in the words of Li Kan: "...It has bothered me that ever since the Yuanhe Reign we have had poems by Bai Juyi and Yuan Zhen whose sensual delicacy has defied the norms.

[30] Bai Juyi is one of the main characters of the 2017 Chinese fantasy film Legend of the Demon Cat, where he is portrayed by Huang Xuan.

It the movie, the poet is solving a murder mystery and struggles to finish his famous poem, "Song of Everlasting Regret."

Japanese painting by Kanō Sansetsu (1590-1651).