Balancing selection

[3] Evidence for balancing selection can be found in the number of alleles in a population which are maintained above mutation rate frequencies.

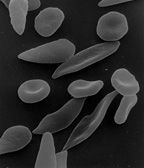

Sickle cell anemia is caused by the inheritance of an allele (HgbS) of the hemoglobin gene from both parents.

In such individuals, the hemoglobin in red blood cells is extremely sensitive to oxygen deprivation, which results in shorter life expectancy.

[5][6] Maintenance of the HgbS allele through positive selection is supported by significant evidence that heterozygotes have decreased fitness in regions where malaria is not prevalent.

In Curacao, the HgbS allele has decreased in frequency over the past 300 years, and will eventually be lost from the gene pool due to heterozygote disadvantage.

Host-parasite interactions may also drive negative frequency-dependent selection, in alignment with the Red Queen hypothesis.

For example, parasitism of freshwater New Zealand snail (Potamopyrgus antipodarum) by the trematode Microphallus sp.

The fitness of a genotype may vary greatly between larval and adult stages, or between parts of a habitat range.

Unbanded is the top dominant trait, and the forms of banding are controlled by modifier genes (see epistasis).

In this species predation by birds appears to be the main (but not the only) selective force driving the polymorphism.

[11][12][13][14][15] Recent work has included the effect of shell colour on thermoregulation,[16] and a wider selection of possible genetic influences is also considered.

[17] In the 1930s Theodosius Dobzhansky and his co-workers collected Drosophila pseudoobscura and D. persimilis from wild populations in California and neighbouring states.