Directional selection

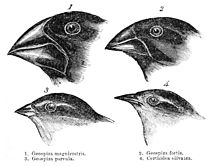

[5] Directional selection can be observed in finch beak size, peppered moth color, African cichlid mouth types, and sockeye salmon migration periods.

[7] Analysis on quantitative trait locus (QTL) effects has been used to examine the impact of directional selection in phenotypic diversification.

[9] In one study, the analysis showed that directional changes in QTLs affecting various traits were more common than expected by chance among diverse species.

[12] The relative ratio test looks at the accumulation of advantageous traits against a neutral model, but needs a phylogenetic tree for comparison.

Darwin first observed this in the publication of his book, On the Origin of Species, and he details how the size of the finches beak differs based on environmental factors.

On the Galápagos Islands west of the coast of Ecuador, there were groups of finches displaying different beak phenotypes.

The changes in diet of the finches based on the environmental wet and dry seasons affected the depth of the birds’ beaks in future generations.

Using the QTL sign test, definitive evidence was used to support the existence of directional selection in the oral jaw apparatus in African cichlids.

Data from 1969–2003 provided by the Alaska Department of Fish and Game were divided into five sets of seven years and plotted for average arrival to the fishery.

[22] Studies carried out in Little Togiak Lake in Alaska, indicate that bear predation has a significant impact on sockeye salmon populations, especially in shallow streams.

Bears often focus on larger male salmon and tend to prefer those that have just arrived at the spawning grounds, particularly in smaller streams where they can catch them more easily.

Additionally, the impact of predation varies among different salmon populations based on their habitat and density; it tends to be more selective in areas where fish are readily accessible.

Overall, these dynamics illustrate how bear predation affects salmon behavior and life cycles, influencing their evolutionary processes.

[22] This study examines the role of lineage-specific directional selection on body size evolution in felids, revealing that several species, including those in the Panthera genus (lions, tigers, leopards, jaguars, snow leopards), the cheetah, and the puma, exhibit evidence of directional selection favoring larger body mass.

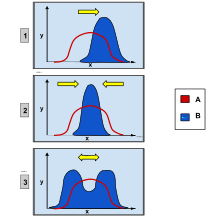

[24] Directional selection can quickly lead to vast changes in allele frequencies in a population because of the cumulative nature of reproduction of the fittest.

[25] Low amount of genetic variation can lead to mass extinctions and endangered species because of the large impact one mutation can have on the entire population if there are only a few specific genes present throughout.

[26] Major roads, waterway pollution, and urbanization all cause environmental selection and could potentially result in changes in allele frequencies.