Disruptive selection

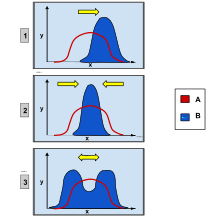

The effect of selection is to promote certain alleles, traits, and individuals that have a higher chance to survive and reproduce in their specific environment.

Since the environment has a carrying capacity, nature acts on this mode of selection on individuals to let only the most fit offspring survive and reproduce to their full potential.

Disruptive selection is inferred to oftentimes lead to sympatric speciation through a phyletic gradualism mode of evolution.

It is seen that often this is more prevalent in environments where there is not a wide clinal range of resources, causing heterozygote disadvantage or selection favoring homozygotes.

Usually complete reproductive isolation does not occur until many generations, but behavioral or morphological differences separate the species from reproducing generally.

These pathways are the result of disruptive selection in intraspecific competition; it may cause reproductive isolation, and finally culminate in sympatric speciation.

For example, what may drive disruptive selection instead of intraspecific competition might be polymorphisms that lead to reproductive isolation, and thence to speciation.

If multiple morphs (phenotypic forms) occupy different niches, such separation could be expected to promote reduced competition for resources.

[16][19] When intraspecific competition is not at work disruptive selection can still lead to sympatric speciation and it does this through maintaining polymorphisms.

Once the polymorphisms are maintained in the population, if assortative mating is taking place, then this is one way that disruptive selection can lead in the direction of sympatric speciation.

Therefore, butterflies will tend to mate with others of the same wing pattern promoting increased fitness, eventually eliminating the heterozygote altogether.

This unfavorable heterozygote generates pressure for a mechanism that cause assortative mating which will then lead to reproductive isolation due to the production of post-mating barriers.

[26][27][28] It is actually fairly common to see sympatric speciation when disruptive selection is supporting two morphs, specifically when the phenotypic trait affects fitness rather than mate choice.

[18][25][30] Disruptive selection is of particular significance in the history of evolutionary study, as it is involved in one of evolution's "cardinal cases", namely the finch populations observed by Darwin in the Galápagos.

This could eventually lead to a situation in which chromosomes with "b" allele die out, making black the only possible color for all subsequent rabbits.