Base erosion and profit shifting

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) define BEPS strategies as "exploiting gaps and mismatches in tax rules".

[a] BEPS activities cost nations 100–240 billion dollars in lost revenue each year, which is 4–10 percent of worldwide corporate income tax collection.

[8] In June 2018 an investigation by tax academic Gabriel Zucman (et alia),[9] estimated that the figure is closer to $200 billion per annum.

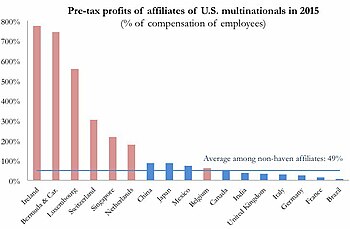

[10] The Tax Justice Network estimated that profits of $660 billion were "shifted" in 2015 due to Apple's Q1 2015 leprechaun economics restructuring, the largest individual BEPS transaction in history.

[14][15] Most BEPS activity is associated with industries with intellectual property ("IP"), namely Technology (e.g. Apple, Google, Microsoft, Oracle), and Life Sciences (e.g. Allergan, Medtronic, Pfizer and Merck & Co) (see here) as our economy is changing to become more digital and knowledge based.

[17][18] Intangible assets such as patents, designs, trademarks (or brands) and copyrights are usually easy to identify, value and transfer, which is why they are attractive in tax planning structures for multinational companies, especially since these rights are not generally geographically bound and are therefore highly mobile.

Then profits can be shifted from the foreign subsidiary to the offshore patent owning company where low to no taxes are applied on the royalties earned.

[21] The popularity of using intra-group debts as a tax avoidance tool is further enhanced by the fact that in general they are not recognized under accounting standards and therefore do not affect consolidated financial statements of MNEs.

It is not surprising that the OECD describes the BEPS risks arising from intra-group debt as the "main tax policy concerns surrounding interest deductions" (emphasis added).

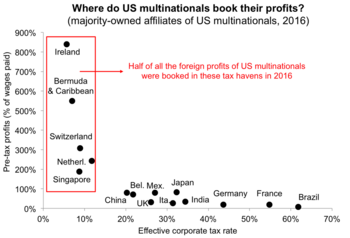

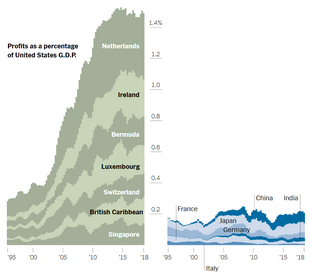

No other non-haven OECD country records as high a share of foreign profits booked in tax havens as the United States.

It was noted that the five major Conduit OFCs, namely, Ireland, the Netherlands, the United Kingdom, Singapore and Switzerland, all have a top-ten ranking in the 2018 Global Innovation Property Centre (GIPC) IP Index".

That is achieved with financial secrecy laws, and by the avoidance of country-by-country reporting ("CbCr") or the need to file public accounts, by multinationals in the haven's jurisdiction.

That comes from schemes that facilitate profit shifting.The complex accounting tools, and the detailed tax legislation, that corporate tax havens require to become OECD-compliant BEPS hubs, requires both advanced international tax-law professional services firms, and a high degree of coordination with the State, who encode their BEPS tools into the State's statutory legislation.

[50] For example, when Ireland was pressured by the EU–OECD to close its double Irish BEPS tool, the largest in history, to new entrants in January 2015,[51] existing users, which include Google and Facebook, were given a five-year extension to 2020.

[52] Even before 2015, Ireland had already publicly replaced the double Irish with two new BEPS tools: the single malt (as used by Microsoft and Allergan), and capital allowances for intangible assets ("CAIA"), also called the "Green Jersey", (as used by Apple in Q1 2015).

[59] For example, the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 ("TCJA") levied 15.5% on the untaxed offshore cash reserves built up by U.S. multinationals with BEPS tools from 2004 to 2017.

[63] An OECD BEPS Multilateral Instrument, consisting of 15 Actions designed to be implemented domestically and through bilateral tax treaty provisions, were agreed at the 2015 G20 Antalya summit.

In a letter to him the group recommended Ireland not adopt article 12, as the changes "will have effects lasting decades" and could "hamper global investment and growth due to uncertainty around taxation".

[67] In August 2016, the Tax Justice Network's Alex Cobham described the OECD's MLI as a failure due to the opt-outs and watering-down of individual BEPS Actions.

[68] In December 2016, Cobham highlighted one of the key anti-BEPS Actions, full public country-by-country reporting ("CbCr"), had been dropped due to lobbying by the U.S.

In June 2017, a U.S. Treasury official explained that the reason why U.S. refused to sign up to the OECD's MLI, or any of its Actions, was because: "the U.S. tax treaty network has a low degree of exposure to base erosion and profit shifting issues".

[73] In July 2018, an Irish tax expert Seamus Coffey, forecasted a potential boom in U.S. multinationals on-shoring their BEPS tools from the Caribbean to Ireland, and not to the U.S. as was expected after TCJA.

[76] There is debate as to whether they are drafting mistakes to be corrected or concessions to enable U.S. multinationals to reduce their effective corporate tax rates to circa 10% (the Trump administration's original target).

[77] In February 2019, Brad Setser from the Council on Foreign Relations (CoFR), wrote an article for The New York Times highlighting material issues with TCJA in terms of curtailing U.S. corporate use of major tax havens such as Ireland, the Netherlands, and Singapore.

[82] Irish-based media highlighted a particular threat to Ireland as the world's largest BEPS hub, regarding proposals to move to a global system of taxation based on where the product is consumed or used, and not where its IP has been located.

[82] The IIEA chief economist described the OECD proposal as "a move last week [that] may bring the day of reckoning closer".

The scope of pillar one is in-scope companies are the multinational enterprises (MNEs) with global turnover above 20 billion euros and profitability above 10% (i.e. profit before tax/revenue) calculated using an averaging mechanism with the turnover threshold to be reduced to 10 billion euros, contingent on successful implementation including of tax certainty on Amount A, with the relevant review beginning 7 years after the agreement comes into force, and the review being completed in no more than one year.

In 2013 the OECD along with G20 has introduced its BEPS Project, which aims to give governments tools to prevent international companies from tax avoidance.

In 2015, the G20 supported the transfer pricing recommendations, which aims to guide governments on how profits of multinational companies should be divided among individual countries.