Nucleic acid tertiary structure

This frequency of twist (known as the helical pitch) depends largely on stacking forces that each base exerts on its neighbours in the chain.

Because interactions with the minor groove are often mediated by the 2'-OH of the ribose sugar, this RNA motif looks very different from its DNA equivalent.

This allows for optimal van der Waals contacts, extensive hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic surface burial, and creates a highly energetically favorable interaction.

For example, the GGC triplex (GGC amino(N-2)-N-7, imino-carbonyl, carbonyl-amino(N-4); Watson-Crick) observed in the 50S ribosome, composed of a Watson-Crick type G-C pair and an incoming G which forms a pseudo-Hoogsteen network of hydrogen bonding interactions between both bases involved in the canonical pairing.

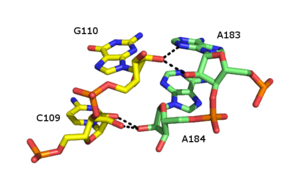

[12] Other notable examples of major groove triplexes include (i) the catalytic core of the group II intron shown in the figure at left [6] (ii) a catalytically essential triple helix observed in human telomerase RNA[7] (iii) the SAM-II riboswitch[14] and (iv) the element for nuclear expression (ENE), which acts as an RNA stabilization element through triple helix formation with the poly(A) tail.

[17] The core of malachite green aptamer is also a kind of base quadruplex with a different hydrogen bonding pattern (See Figure).

Two important functions are the binding potential with ligands or proteins, and its ability to stabilize the whole tertiary structure of DNA or RNA.

[17] Along with these functions, the G-quadruplex in the mRNA around the ribosome binding regions could serve as a regulator of gene expression in bacteria.

The relative stability of nearest neighbor interactions can be used to predict favorable coaxial stacking based on known secondary structure.

Walter and Turner found that, on average, prediction of RNA structure improved from 67% to 74% accuracy when coaxial stacking contributions were included.

[25] In the self-splicing group II intron from Oceanobacillus iheyensis, the IA and IB stems coaxially stack and contribute to the relative orientation of the constituent helices of a five-way junction.

DNA origami structures contain a large number of double helixes with exposed blunt ends.

These structures were observed to stick together along the edges that contained these exposed blunt ends, due to the hydrophobic stacking interactions.

[29] By combining these rationally designed DNA nanostructures and DNA-PAINT super-resolution imaging, researchers discerned individual strength of stacking energies between all possible dinucleotides.

[30] Early measurements of coaxial stacking were performed using biochemical assays that studies the relative migration of different nucleic acid molecules based on their conformation and the kind of interactions present.

The force needed to pull these bundles apart using optical tweezers could then be analyzed to measure the base-pair stacking energies.

[32] These measurements were performed mainly under non-equilibrium conditions and various extrapolations were made to arrive at the exact values of coaxial stacking between bases.

Recent single-molecule studies using DNA nanostructures and DNA-PAINT super-resolution microscopy has allowed for measurement of these interaction between dinucleotides using in-depth kinetic analysis of binding times of short DNA molecules to their complimentary sequences in the presence or absence of DNA-stacking interactions.

[30] Tetraloop-receptor interactions combine base-pairing and stacking interactions between the loop nucleotides of a tetraloop motif and a receptor motif located within an RNA duplex, creating a tertiary contact that stabilizes the global tertiary fold of an RNA molecule.

[46][47] Numerous forms of ribose zipper have been reported, but a common type involves four hydrogen bonds between 2'-OH groups of two adjacent sugars.

Multivalent organic cations such as spermidine or spermine are also found in cells and these make important contributions to RNA folding.

Metal-binding sites are often localized in the deep and narrow major groove of the RNA duplex, coordinating to the Hoogsteen edges of purines.

In particular, metal cations stabilize sites of backbone twisting where tight packing of phosphates results in a region of dense negative charge.

In many of these motifs, absence of the monovalent or divalent cations results in either greater flexibility or loss of tertiary structure.

[57] Magnesium is vital in stabilizing these kinds of junctions in artificially designed structures used in DNA nanotechnology, such as the double crossover motif.

In their seminal 1953 paper, Watson and Crick suggested that van der Waals crowding by the 2`OH group of ribose would preclude RNA from adopting a double helical structure identical to the model they proposed - what we now know as B-form DNA.

In 1971, Kim et al. achieved another breakthrough, producing crystals of yeast tRNAPHE that diffracted to 2-3 Ångström resolutions by using spermine, a naturally occurring polyamine, which bound to and stabilized the tRNA.

This proved limiting to the field for many years, in part because other known targets - i.e., the ribosome - were significantly more difficult to isolate and crystallize.

[62] This unfortunate lack of scope would eventually be overcome largely because of two major advancements in nucleic acid research: the identification of ribozymes, and the ability to produce them via in vitro transcription.

In 1994, McKay et al. published the structure of a 'hammerhead RNA-DNA ribozyme-inhibitor complex' at 2.6 Ångström resolution, in which the autocatalytic activity of the ribozyme was disrupted via binding to a DNA substrate.