Bat virome

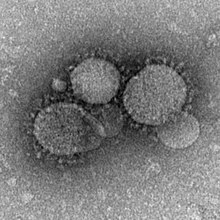

While research clearly indicates that SARS-CoV-2 originated in bats,[3] it is unknown how it was transmitted to humans, or if an intermediate host was involved.

There is no firm evidence that butchering or consuming bat meat can lead to viral transmission, though this has been speculated.

A 2018 study found that bats have a dampened STING response compared to other mammals, which could allow them to respond to viral threats without over-responding.

[6] The zoonotic viruses have four possible routes of transmission to humans: contact with bat body fluids (blood, saliva, urine, feces); intermediate hosts; environmental exposure; and blood-feeding arthropods.

[4] A 2020 review of mammals and birds found that the identity of the taxonomic groups did not have any impact on the probability of harboring zoonotic viruses.

They can also be surveyed using molecular detection techniques like PCR (polymerase chain reaction), which can be used to replicate and amplify viral sequences.

[7] Diverse herpesviruses have been found in bats in North and South America, Asia, Africa, and Europe,[18] including representatives of the three subfamilies, alpha-, beta-, and gammaherpesviruses.

Another strain of Nelson Bay orthoreovirus associated with bats is Pulau virus, which was first identified from the small flying fox of Tioman Island in 2006.

[25] Astroviruses have been found in several genera of bat in the Old World, including Miniopterus, Myotis, Hipposideros, Rhinolophus, Pipistrellus, Scotophilus, and Taphozous,[18] though none in Africa.

Bat caliciviruses are similar to the genera Sapovirus and Valovirus, with noroviruses also detected from two microbat species in China.

[28][31] The first human case of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) was in June 2012 in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.

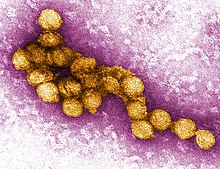

Serological studies indicate that West Nile virus may also be present in bats in North America and the Yucatán Peninsula.

Saint Louis encephalitis virus has been detected in bats in the US states of Texas and Ohio, as well as the Yucatán Peninsula.

[40] Among others, it has been posited that the Western African Ebola virus epidemic began with a spillover event from an Angolan free-tailed bat to a human.

[47] Marburg virus has been detected in Egyptian fruit bats in Gabon, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Kenya, and Uganda.

[47] Lloviu virus, a kind of filovirus in the genus Cuevavirus, has been identified from the common bent-wing bat in Spain.

[51][52] After transmission has occurred, the average human is asymptomatic for two months, though the incubation period can be as short as a week or as long as several years.

[55] Bats are the most common source of rabies in humans in North and South America, Western Europe, and Australia.

[56] Many feeding guilds of bats may transmit rabies to humans, including insectivorous, frugivorous, nectarivorous, omnivorous, sanguivorous, and carnivorous species.

[52] In North America, about half of human rabies instances are cryptic, meaning that the patient has no known bite history.

Outside of bites, rabies virus exposure can also occur if infected fluids come in contact with a mucous membrane or a break in the skin.

While birds are the primary reservoir for the genus Alphainfluenzavirus, a few bat species in Central and South America have also tested positive for the viruses.

It is unclear how horses become infected with Hendra virus, though it is believed to occur following direct exposure to flying fox fluids.

[16] It was determined that flying foxes were also the reservoir of the virus, with domestic pigs as the intermediate host between bats and humans.

In Bangladesh, the primary mode of transmission of Nipah virus to humans is through the consumption of date palm sap.

It has been speculated that the virus may also be transmitted to humans by eating fruit partially consumed by flying foxes, or by coming into contact with their urine, though no definitive evidence supports this.

[64] An additional zoonotic paramyxovirus that bats harbor is Menangle virus, which was first identified at a hog farm in New South Wales, Australia.

[16] Sosuga pararubulavirus is known to have infected one person—an American wildlife biologist who had conducted bat and rodent research in Uganda.

Bats are the reservoir of Cedar virus, a paramyxovirus first discovered in flying foxes South East Queensland.

[16] Tioman pararubulavirus has been isolated from the urine of the small flying fox, which causes fever in some domestic pigs after exposure, but no other symptoms.