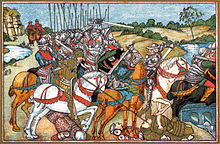

Battle of Barnet

Deprived of Warwick's support, the Lancastrians suffered their final defeat at the Battle of Tewkesbury on 4 May, which marked the end of the reign of Henry VI and the restoration of the House of York.

The Wars of the Roses were a series of conflicts between various English lords and nobles in support of two different royal families descended from Edward III.

Edward IV, leader of the Yorkists, seized the throne from the Lancastrian king, Henry VI,[2] who was captured in 1465 and imprisoned in the Tower of London.

[5] As the Yorkists tightened their hold over England, Edward rewarded his supporters, including his chief adviser, Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick, elevating them to higher titles and awarding them land confiscated from their defeated foes.

[8] The young king, however, favoured ties with Burgundy and, in 1464, further angered the Earl by secretly marrying Elizabeth Woodville; as an impoverished Lancastrian widow, she was regarded by the Yorkists as an unsuitable queen.

The first was the marriage of his aunt, Lady Katherine Neville, over 60 years old, to Elizabeth's 20-year-old brother, John Woodville, a pairing considered outside of normal wedlock by many people.

The other was his nephew's fiancée, the daughter of Henry Holland, 3rd Duke of Exeter, who was taken as a bride by the Queen's son, Thomas Grey, with Edward's approval.

After winning the Battle of Edgcote on 26 July 1469, the Earl found the Yorkist king deserted by his followers, and brought him to Warwick Castle for "protection".

Warwick invaded England at the head of a Lancastrian army and, in October 1470, forced Edward to seek refuge in Burgundy, then ruled by the King's brother-in-law Charles the Bold.

The throne of England was temporarily restored to Henry VI;[18] on 14 March 1471, Edward brought an army back across the English Channel, precipitating the Battle of Barnet a month later.

[24] His trade policies, which aimed to expand and protect markets for English commerce, pleased local merchants, who were also won over by the Yorkist king's personality.

The euphoria of a change in government had ebbed and the people blamed Edward for failing to "bring the realm of England in[to] great popularity and rest" and allowing Yorkist nobles to go unpunished for abuses.

Clarence lost faith in the Earl when Warwick defected to the Lancastrians and married off his other daughter, Anne, to their prince in order to cement his new allegiance.

When Edward launched his campaign to retake England, Clarence accepted his brother's offer of pardon and rejoined the Yorkists at Coventry on 2 April 1471.

[31] Warwick had fought for the House of York since the early stages of the Wars of the Roses and alongside his cousin, Edward IV, in many of the battles.

Early historians described him as a military genius, but by the 20th century his tactical acumen was reconsidered; Philip Haigh suspects that the Earl largely owed some of his victories, such as the First Battle of St Albans, to being in the right place at the right time.

[38] Not much is known about the early history of John de Vere, 13th Earl of Oxford, another Lancastrian commander; the chronicles mention little about him until the Battle of Losecoat Field.

[43] A proven enemy of the Nevilles,[44] Exeter bore a grudge particularly against Warwick for displacing him from his hereditary role of Lord High Admiral in 1457.

Edward's march was unopposed at the beginning because he was moving through lands that belonged to the Percys, and the Earl of Northumberland was indebted to the Yorkist king for the return of his northern territory.

[58] The earl displaced his entire line slightly to the west; a depression at the rear of his left flank could impede Exeter's group if they had to fall back.

The Lancastrian left wing, however, was suffering treatment similar to that Oxford had inflicted on its counterpart; Gloucester exploited the misaligned forces and beat Exeter back.

Edward exhibited the brothers' naked corpses in St. Paul's Cathedral for three days to quell any rumours that they had survived, before allowing them to be laid to rest in the family vault at Bisham Abbey.

Twelve years later Oxford escaped from prison and joined Henry Tudor's fight against the Yorkists, commanding the Lancastrian army at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485.

In the play, Montagu is killed while trying to save his brother (Shakespeare's source material included Hall's 1548 The Union of the Two Noble and Illustrate Famelies of Lancastre and Yorke),[95][96] and Warwick is dragged in by Edward IV and left to speak his dying words to Oxford and Somerset.

[99] Professor of English John Cox suggests that Shakespeare did not share the impression given in post-battle ballads that Edward's triumph was divinely ordained.

He argues that Shakespeare's placement of Clarence's last act of betrayal immediately before the battle suggests that Edward's rule stems from his military aggression, luck, and "policy".

[101] English Heritage, a government body in charge of conservation of historic sites, roughly locates the battlefield in an area 800 to 1600 metres (0.5 to 1.0 mile) north of the town of Barnet.

Over the centuries, much of the terrain has changed, and records of the town's boundaries and geography are not detailed enough for English Heritage or historians to conclude the exact location of the battle.

[nb 3] English Heritage suggests that a 15th-century letter from a Hanseatic merchant, Gerhard von Wessel, helps to identify the battlefield via geological features.

"[58]The battle is referred to in the coat of arms of the London Borough of Barnet which display a red and a silver rose in the top of the shield and two crossed swords in the crest.