Battle of Wakefield

After open warfare broke out between the factions and Henry became his prisoner, he laid claim to the throne, but lacked sufficient support.

There were increasingly bitter divisions among the officials and councillors who governed in Henry's name, mainly over the conduct of the Hundred Years' War with France.

York argued for a more vigorous prosecution of the war, to recover territories recently lost to the French,[1] while Somerset belonged to the party which tried to secure peace by making concessions.

[2] York had been Lieutenant in France for several years and resented being supplanted in that office by Somerset, who had then failed to defend Normandy against French armies.

The Great Council of peers appointed York Lord Protector and he governed the country responsibly, but Henry recovered his sanity after eighteen months and restored Somerset to favour.

At the First Battle of St Albans, many of York's and Salisbury's rivals and enemies were killed, including Somerset, the Earl of Northumberland (whose family, the Percys, had been involved in a long-running feud with the Nevilles) and Lord Clifford.

[11] He and the Nevilles concentrated their forces near York's stronghold at Ludlow Castle in the Welsh Marches but at the confrontation with the much larger royal army which became known as the Battle of Ludford, some of Warwick's contingent from the garrison of Calais, led by experienced captain Andrew Trollope, defected overnight.

[13] Lancastrian attempts to reassert their authority over Ireland and Calais failed, but York and his supporters were declared traitors and attainted.

The victorious Lancastrians became reviled for the manner in which their army had looted the town of Ludlow after the Yorkist surrender at Ludford Bridge, and the repressive acts of a compliant Parliament of Devils which caused many uncommitted peers to fear for their own property and titles.

They later proceeded by ship to Scotland, where Margaret gained troops and other aid for the Lancastrian cause from the queen and regent, Mary of Guelders, in return for the surrender of the town and castle of Berwick upon Tweed.

[10] Faced with these challenges to his authority as Protector, York despatched his eldest son Edward to the Welsh Marches to contain the Lancastrians in Wales and left the Earl of Warwick in charge in London.

The Nevilles were one of the wealthiest and most influential families in the North and in addition to controlling large estates, the Earl of Salisbury had held the office of Warden of the Eastern March for several years.

On 16 December, at the Battle of Worksop in Nottinghamshire, York's vanguard clashed with Somerset's contingent from the West Country moving north to join the Lancastrian army, and was defeated.

In a stratagem possibly devised by the veteran Andrew Trollope (who by Waurin's account had also sent messages to York via feigned deserters that he was prepared to change sides once again)[29] half the Lancastrian army under Somerset and Clifford advanced openly towards Sandal Castle, over the open space known as "Wakefield Green" between the castle and the River Calder, while the remainder under Ros and the Earl of Wiltshire were concealed in the woods surrounding the area.

[30][nb 2] York was probably short of provisions in the castle and, seeing that the enemy were apparently no stronger than his own army, seized the opportunity to engage them in the open rather than withstand a siege while waiting for reinforcements.

[33] Other accounts suggested that, possibly in addition to Trollope's deception, York was fooled by some of John Neville of Raby's forces displaying false colours into thinking that reinforcements sent by Warwick had arrived.

[10] For example, historian John Sadler states that there was no Lancastrian deception or ambush; York led his men from the castle on a foraging expedition (or by popular belief, to rescue some of his foragers who were under attack)[37] and as successive Lancastrian contingents joined the battle (the last being Clifford's division, encamped south and east of Sandal Magna), York's army was outnumbered, surrounded and overwhelmed.

In Edward Hall's words: ... but when he was in the plain ground between his castle and the town of Wakefield, he was environed on every side, like a fish in a net, or a deer in a buckstall; so that he manfully fighting was within half an hour slain and dead, and his whole army discomfited.

Some later works support the folklore that he suffered a crippling wound to the knee and was unhorsed, and he and his closest followers then fought to the death at that spot;[38] others relate the account that he was taken prisoner (by one Sir James Luttrell of Devonshire), mocked by his captors and beheaded.

[40] His son Edmund, Earl of Rutland, attempted to escape over Wakefield Bridge, but was overtaken and killed, possibly by Clifford in revenge for his father's death at St Albans.

Although the Lancastrian nobles might have been prepared to allow Salisbury to ransom himself, he was dragged out of Pontefract Castle and beheaded by local commoners, to whom he had been a harsh overlord.

The northern Lancastrian army which had been victorious at Wakefield was reinforced by Scots and borderers eager for plunder, and marched south.

They defeated Warwick's army at the Second Battle of St Albans and recaptured the feeble-minded King Henry, who had been abandoned on the battlefield for the third time, but were refused entry to London[43] and failed to occupy the city.

At Wakefield and in every battle in the Wars of the Roses thereafter, the victors would eliminate not only any opposing leaders but also their family members and supporters, making the struggle more bitter and revenge driven.

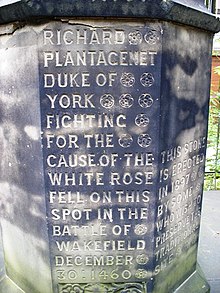

[45] Archaeologist Rachel Askew suggests that the memorial cross to the Duke of York may be fictional as the late-16th- and early-17th-century antiquarian John Camden did not mention it in his description of the location.