Battle of Towton

[4] Fought for ten hours between an estimated 50,000 soldiers in a snowstorm on Palm Sunday, the Yorkist army achieved a decisive victory over their Lancastrian opponents.

In October 1460, Parliament passed the Act of Accord naming York as Henry's successor, but neither the queen nor her Lancastrian allies would accept the disinheritance of her son, Edward of Westminster, Prince of Wales.

The Lancastrians backed the reigning King of England, Henry VI, a weak and indecisive man who suffered from intermittent bouts of madness.

[5] The leader of the Yorkists was initially Richard, Duke of York, who resented the dominance of a small number of aristocrats favoured by the king, principally his close relatives, the Beaufort family.

Even York's closest supporters among the nobility were reluctant to usurp the dynasty; the nobles passed by a majority vote the Act of Accord, which ruled that the duke and his heirs would succeed to the throne upon Henry's death.

She had fled to Scotland after the Yorkist victory at Northampton; there she began raising an army, promising her followers the freedom to plunder on the march south through England.

The duke and his second son, Edmund, Earl of Rutland, were decapitated by the Lancastrians and their heads were impaled on spikes atop the Micklegate Bar, a gatehouse of the city of York.

They liberated Henry after defeating the Yorkist army of Richard Neville, Earl of Warwick, in the Second Battle of St Albans and continued pillaging on their way to London.

The proclamation gained greater acceptance than Richard of York's earlier claim, as several nobles opposed to letting Edward's father ascend the throne viewed the Lancastrian actions as a betrayal of the legally established Accord.

[15] The young king summoned and ordered his followers to march towards York to take back his family's city and to depose Henry formally through force of arms.

[25] In contrast the 18-year-old Edward was a tall and imposing sight in armour and led from the front: his preference for bold offensive tactics determined the Yorkist plan of action for this engagement.

[30] Edward relied heavily on Warwick's uncle, Lord Fauconberg, a veteran of the Anglo-French wars, highly regarded by contemporaries for his military skills.

[31] He demonstrated this in a wide range of roles, having captained the Calais garrison,[31] led naval piracy expeditions in the Channel,[32] and commanded the Yorkist vanguard at Northampton.

[33] The senior Lancastrian general was Henry Beaufort, Duke of Somerset, an experienced leader credited with victories at Wakefield and St Albans, although others suggest they were due to Sir Andrew Trollope.

The paucity of such primary sources led early historians to adopt Hall's chronicle as their main resource for the engagement, despite its authorship 70 years after the event and questions over the origin of his information.

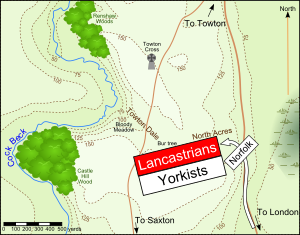

[42] According to Gravett and fellow military enthusiast Trevor James Halsall, Somerset's decision to engage the Yorkist army on this plateau was sound.

[43] Waurin's account gave rise to the suggestion that Somerset ordered a force of mounted spearmen to conceal itself in Castle Hill Wood, ready to charge into the Yorkist left flank at an opportune time in battle.

[50] Noticing the direction and strength of the wind, Fauconberg ordered all Yorkist archers to step forward and unleash a volley of their arrows from what would be the standard maximum range of their longbows.

They found it difficult to judge the range and pick out their targets and their arrows fell short of the Yorkist ranks; Fauconberg had ordered his men to retreat after loosing one volley, thus avoiding any casualties.

Seeing the advancing mass of men, the Yorkist archers shot a few more volleys before retreating behind their ranks of men-at-arms, leaving thousands of arrows in the ground to hinder the Lancastrian attack.

[2][52] As the Yorkists reformed their ranks to receive the Lancastrian charge, their left flank came under attack by the horsemen from Castle Hill Wood mentioned by Waurin.

The Lancastrians continuously threw fresher men into the fray and gradually the numerically inferior Yorkist army was forced to give ground and retreat up the southern ridge.

In 1996 workmen at a construction site in the village of Towton uncovered a mass grave, which archaeologists believed to contain the remains of men who were slain during or after the battle in 1461.

[2][3] A more recent analysis of the sources and archaeological evidence, which posits that accounts of Towton were combined with those of the actions of Ferrybridge and Dintingdale, suggests total casualty figures in the range 2,800 – 3,800.

[81] Historian Bertram Wolffe said it was thanks to Shakespeare's dramatisation of the battle that the weak and ineffectual Henry was at least remembered by English society, albeit for his pining to have been born a shepherd rather than a king.

[92] An episode in C. J. Sansom’s historical novel Sovereign, set in 1541, sixty years after the battle, concerns a Towton farmer appealing to King Henry VIII to be compensated for the time and effort he has to spend on turning over to the Church the skeletons discovered nearly every day on his land.

Obtaining an accurate figure for casualties has been complicated: remains were either moved or used by farmers as fertiliser, and corpses were generally stripped of clothing and non-perishable items before burial.

[96] Lord Dacre was buried at the church of All Saints in Saxton and his tomb was reported in the late 19th century to be well maintained, although several of its panels had been weathered away.

For several centuries a local farmer had scoured a hill figure, the Red Horse of Tysoe, each year, as part of the terms of his land tenancy.

Although the origins of the tradition have never been conclusively identified, it was locally said this was done to commemorate the Earl of Warwick's inspirational deed of slaying his horse to show his resolve to stand and fight with the common soldiers.