Battle of Tewkesbury

The term Wars of the Roses refers to the informal heraldic badges of the two rival houses of Lancaster and York, which had been contending for the English throne since the late 1450s.

They became estranged when Edward spurned the French diplomatic marriage that Warwick was seeking for him and instead married Elizabeth Woodville, widow of an obscure Lancastrian gentleman, in secret in 1464.

Edward, meanwhile, reversed Warwick's policy of friendship with France by marrying his sister Margaret to Charles the Bold, the Duke of Burgundy.

Edward fled to King's Lynn, where he took ship for Flanders, part of Burgundy, accompanied only by his youngest brother Richard of Gloucester and a few faithful adherents.

[12] In London Warwick released King Henry, led him in procession to Saint Paul's cathedral, and installed him in Westminster palace.

His alliance with Louis of France and his intention to declare war on Burgundy was contrary to the interests of the merchants, as it threatened English trade with Flanders and the Netherlands.

In November 1470 Parliament declared that Prince Edward and his (putative) descendants were Henry's heirs to the throne; Clarence would become king only if the Lancastrian line of succession failed.

As an obvious counter to Warwick, he supplied King Edward with money (50,000 florins), ships, and several hundred men (including handgunners).

[14] He touched briefly on the English coast at Cromer but found that the Duke of Norfolk, who might have supported him, was away from the area and that Warwick controlled that part of the country.

Instead, his ships made for Ravenspurn, near the mouth of the River Humber, where Henry Bolingbroke had landed in 1399 on his way to reclaim the Duchy of Lancaster and ultimately depose Richard II.

Storms forced her ships back to France several times, and she and Prince Edward finally landed at Weymouth in Dorsetshire on the same day the Battle of Barnet was fought.

Although he had given many of his supporters and troops leave after the victory at Barnet, he was nonetheless able to rapidly muster a substantial force at Windsor, just west of London.

It was difficult at first to determine Margaret's intentions, as the Lancastrians had sent out several feints that suggested they might be making directly for London, but Edward's army set out for the West Country within a few days.

Believing that the Lancastrians were about to offer battle, Edward temporarily halted his army while the stragglers caught up and the remainder could rest after their rapid march from Windsor.

He sent urgent messages to the governor, Sir Richard Beauchamp, ordering him to bar the gates to Margaret and man the city's defences.

A farmhouse then known as Gobes Hall marked the centre of the Lancastrian position; nearby was "Margaret's camp", earthworks of uncertain age.

Queen Margaret is said to have spent the night at Gobes Hall, before hastily taking refuge on the day of battle in a religious house some distance from the battlefield.

[20] The main strength of the Lancastrians' position was provided by the ground in front, which was broken up by hedges, woods, embankments, and "evil lanes".

At 17 Prince Edward was no stranger to battlefields, having been given by his mother the task of condemning to death Yorkist prisoners taken at the Second Battle of St Albans, but he lacked experience of actual command.

[21] A small river, the Swilgate, protected Devon's left flank, before curving behind the Lancastrian position to join the Avon.

[3] He then "displayed his bannars: dyd blowe up the trompets: commytted his caws and qwarell to Almyghty God, to owr most blessyd lady his mother: Vyrgyn Mary, the glorious Seint George, and all the saynts: and advaunced, directly upon his enemyes.

"[22] As they moved towards the Lancastrian position, King Edward's army found that the ground was so broken up by woods, ditches, and embankments that it was difficult to attack in any sort of order.

At the vital moment, the 200 spearmen Edward had earlier posted in the woods far out on the left attacked Somerset from his own right flank and rear, as Gloucester's battle also joined in the fighting.

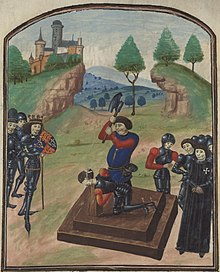

According to legend (recounted in Edward Hall's chronicle, written several years afterwards though from first-hand accounts), he did not wait for an answer but dashed out Wenlock's brains with a battleaxe[24] before seeking sanctuary in the Abbey.

Among the leading Lancastrians who died on the field were Somerset's younger brother John Beaufort, Marquess of Dorset, and the Earl of Devon.

However, two days after the battle, Somerset and other leaders were dragged out of the Abbey and ordered by Gloucester and the Duke of Norfolk to be put to death after perfunctory trials.

King Henry VI died in the Tower of London that night, at the hands of or by the order of Richard of Gloucester according to several near contemporary accounts.

With the deaths of Somerset and his younger brother, the House of Beaufort, who were distant cousins of Henry VI and had a remote claim to succeed him, had been almost exterminated.

Henry escaped from Wales with Jasper Tudor, his paternal uncle, and remained in exile in Brittany for the remainder of Edward's reign.

[28] The Tewkesbury Battlefield Society erected a monument to the battle in the form of two sculptures 5 metres (16 ft) high, of a victorious mounted knight and a defeated horse.