Battle of Bloody Brook

This major defeat amongst others elicited aggressive responses by the English, such as a preventive war against the Narragansett that winter, and the 1676 Peskeompscut Massacre, which ended Indigenous dominance of the Connecticut River valley.

[3] Although related linguistically, the nations of the central Connecticut River valley operated their trade and diplomacy autonomously, participated in far-reaching intertribal alliances, and transacted agreements that preserved traditional access to natural resources.

[4] In contrast, the total population of the seven small English towns spread along the 66 miles of the mid-Connecticut River valley (the western border of the Massachusetts Bay Colony) was approximately 350 men and women, and roughly 1,100 children.

[1] Although an anti-Kanienkehaka alliance with the Pocumtuc, Sokoki, Pennacook, Kennebec Abenaki, Mohicans, French Jesuit missionaries and the Narragansett was formed in 1650, friendly relations were restored with the Kanienkehaka (Mohawks) by the late 1650's.

The deal also secured safe access to the newly acquired lucrative Hudson Valley fur trade for Pynchon and his sub-traders, and redirected Kanienkehaka retribution towards the Pocumtuc and their allies.

Bruchac argues that the wampum generated from these sales may have been particularly attractive to the Pocumtuc, in their desire to exchange them as tributes of peace with the Kanienkehaka, contributing to the repair of Pocumtuc-Kanienkehaka relations in subsequent years.

This may have been a significant factor behind the shift in the Pocumtuc's strategy, as four subsequent land deeds were signed in quick succession between 1667 and 1674, with at least two directly dealt to John Pynchon also neglecting traditional rights.

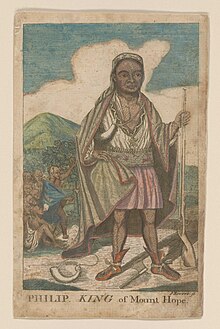

[1] In the aftermath of the Siege of Brookfield in the first few months of King Philip's War, the New England Confederation raised several companies of English militia and indigenous allies to protect the western border of the colony, as the settlements there were not able to conscript enough men for their defense.

[7] In early September, indigenous forces conducted two raids the English village of Deerfield at Pocumtuc, burning most of the houses, stealing multiple horse-loads of beef and pork, killing one garrison soldier & several horses, then retired to a hill nearby.

When news reached Northampton, part of Lathrop's company along with volunteers from Hadley marched to Deerfield to attack the encampment with the local garrison, but found the site abandoned.

[2][8] One day after the initial raid on Deerfield, a Pocumtuc and Nashaway force under Monoco attacked Northfield, the northernmost English settlement in the Massachusetts Bay Colony's western border, again burning most of the houses and driving away the cattle.

Two days later, apparently unaware of the original assault, Beers and 20 of the 36 men in his company were ambushed and killed at Saw Mill Brook by a war party led by Monoco and Sagamore Sam, during an attempt to bolster the garrison at Northfield.

[4][2] After a recruiting trip, Major Treat re-fortified himself in Hadley on either the 25th or 26th of September with more Connecticut colonial troops, with Captain Mason arriving soon after with a company of Mohegan and Pequot warriors.

[2] Deciding to go on the defensive by strengthening the garrisons,[7] while also faced with a long term campaign, commanders in Hadley needing to feed ~350 colonial troops, Mohegan & Pequot allies, and refugees looked to Pocumtuc (contemporaneously also referred to as Deerfield), where settlers had managed to cut and stack a considerable quantity of corn.

[4] Despite Mosely's scouting efforts, the war party crossed the river undetected and surveilled Lathrop's movements, keeping the English completely unaware that any sizeable force was in the area.

[2][9] On the 28th of September 1675, a large Pocumtuc, Nipmuc, and Wampanoag force of at least several hundred warriors laid a well-planned and executed ambush on approximately 67 English militia, 17 teamsters from Deerfield, and their slow-moving ox carts, as they crossed Muddy Brook.

The approximate site of the ambush was a gently flowing stream in a small clearing, bordered by a wet floodplain and surrounded by thickets,[4][7] roughly 5 miles (8.0 km) from where they set off, in what is today South Deerfield.

[4] Deerfield historian Epaphras Hoyt suggests that the main body of English troops had crossed the brook, and were waiting for the slow moving teams of carts to negotiate the rough roads.

[2] Fighting soon continued following the arrival of roughly 70 Massachusetts Bay militia under Captain Mosely from Deerfield, who are said to have repeatedly charged the much larger force in a more extended engagement, moving deep into the woods.

Finally, the arrival of 100 Connecticut colony militia under Major Treat, and 60 Mohegan warriors under Attawamhood from Hadley forced the indigenous war party into retreat,[2] with the battle possibly only ending at nightfall.

Pending negotiations and Metacomet's visit to the region in response, more indigenous communities moved to fishing spots in large numbers in order to secure their provisions, relaxing their defenses and relying on opportune moments for raiding English personnel and livestock.

After a raid on Deerfield's fields dispersed 70 English cattle, Captain William Turner and his men launched a surprise retaliatory night attack at Pesekeompscut fishing village, killing 300 people (mostly women and children).

The massacre was a turning point in King Philip's War, and with Metacomet's death in the same year, this led to the eventual expulsion of most indigenous people from the Connecticut River valley.

However, the Pocumtuc were subject to duplicitous deals regarding land rights and tit-for-tat extrajudicial killings, and would be forcibly expelled from their homeland by Pynchon and Deerfield's English settlers due to prejudice.

Thereafter, the table stone was transferred to the front yard of a private home, a sidewalk, and a nearby barn, until it was reset in its current location on the east side of North Main Street in South Deerfield.

The newly formed Pocumtuck Valley Memorial Association and citizens of Deerfield organized a day long celebration, with a parade to the monument followed by carriages carrying event guests, dignitaries and local citizenry, and crowds of spectators lining the way.

[4]A second speaker, George Loring of Essex County, informed the thousands listening that the Battle of Bloody Brook's significance was as “an incident in the infancy of a powerful nation, and one occurring at the critical period of the most important social and civil event known to man, the founding of a free republic on the western continent.” Recognizing that Irish, eastern European, and other relatively recent newcomers to the Valley lacked genealogical connections to this 17th-century history, Robert R. Bishop urged all to remember that the “martyred blood at Bloody Brook should inspire us to do deeds of manly, patriotic devotion.”[4] The 300th year anniversary of Bloody Brook in 1975, according to Mathews and Thomas, reflected a significant change in peoples’ minds about the significance of the monument and the relationship with history.

"[4]Professor Margaret Bruchac argues that during the early 1800s, New England’s Euro-American citizens began embracing commemorative events, such as the anniversaries of the Battle of Bloody Brook, as platforms that served as public performances of the white ownership of history and the Connecticut River valley.

Bruchac argues that Sheldon "used bloody examples from Deerfield’s history as a rhetorical device to paint the Pocumtuck Indians and, by extension, all Native people as inherently dangerous and untrustworthy.

"[1] In evaluating the historiography of the colonial history of the Connecticut River valley, Bruchac states:I suggest that regional nineteenth-century historians consciously sifted the records to select historical anecdotes that emphasized Indian hostilities for dramatic impact.