Bavaria (symbol)

The Tellus Bavarica has been a common allegory of the "Bavarian earth" for many centuries, appearing in many different forms, including in coats of arms, on paintings, as a relief depiction, for example above house entrances, and as a statue.

An easily accessible one can be seen in Munich's Hofgarten: The dome of the central "Dianatempel" was originally crowned by a bronze statue of Diana by Hubert Gerhard, which Hans Krumpper presumably transformed into an allegory of Bavaria in 1623 by adding an elector's hat to her helmet and placing an orb in her hand instead of a wreath of corn.

[2] In 1773, Bartolomeo Altomonte created parts of the Baroque decoration of the Fürstenzell monastery near Passau and placed Bavaria in the center of the ceiling fresco in the Hall of Princes.

In 1805, the artist Marianne Kürzinger created a completely different version of a Bavarian state allegory in her oil painting Gallia Protects Bavaria The picture shows a young, delicate allegory of the country in a white and blue robe, fleeing from the impending storm into the arms of the approaching Gallia, while the Bavarian lion throws itself against the threat.

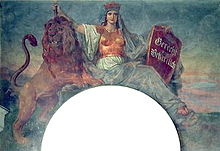

Around a quarter of a century later, Peter von Cornelius, together with other artists involved in the decoration of the Munich Hofgarten arcades, created a much more self-confident allegory of Bavaria as a fresco: this peaceful but defensive Bavaria wears a breastplate and a mural crown, in her right hand she holds an inverted spear as a sign of peace, and in her left a shield with King Ludwig I's motto "Just and Persevering".

However, here the artist placed the allegory in front of an Alpine landscape with a view of Bad Tölz in the background and added a town coat of arms in the foreground.

It forms a conceptual and design unit, despite some breaks, with the three-winged Doric columned hall surrounding it, standing above it on its base.

These motivations and goals subsequently motivated him to undertake several construction projects for national monuments such as the Konstitutionssäule in Gaibach (1828), the Walhalla east of Regensburg above the Danube and the village of Donaustauf (1842), the Ruhmeshalle in Munich (1853) and the Befreiungshalle near Kelheim (1863), all of which were privately financed by the king and which, in terms of form and content, purpose and reception, form an artistic and political unity that is unique in Germany, despite all the internal contradictions.

Ludwig, who succeeded his father on the royal throne after his death in 1825, felt a close connection to Greece, was a fervent admirer of Greek antiquity and wanted to transform his capital Munich into an "Isar-Athens".

As early as the time he was crown prince, Ludwig developed the plan to erect a patriotic monument in the royal seat of Munich, and subsequently had lists and directories of "great" Bavarians from all classes and professions drawn up.

In her left hand, the Bavaria holds a wreath at hip height with her arm outstretched, which she symbolically donates to the honored personalities.

It was evidently part of Ludwig's strategy to incorporate the opposing artistic views into the design of one and the same patriotic monument project in order to unite the conflicting camps under the umbrella of the nation.

The redesign of the Bavaria coincided with the so-called Rhine crisis of 1840/41 and thus took place at a time of patriotic uprisings against the "arch-enemy" France.

In the process, the initially stiff depiction was given "inner movement" and he "succeeded in giving the compact colossal statue with its carefully suggested contrapposto position lightness and a relaxed posture.

"[7] In the case of the bearskin, the oak wreath and the sword, the attributes of the Bavaria are relatively easy to explain from the artistic and political context of its creation.

From the end of 1839, Schwanthaler and a number of assistants gradually created a plaster model of the Bavaria in its original size on the grounds of the ore foundry.

In the late summer of 1843, the completed full-size model could then be broken down into individual parts, which Stiglmaier and Miller then used as templates for the respective casting molds.

On September 11, 1844, the head of the Bavaria was cast from the bronze of Turkish cannons that had sunk with the Egyptian-Turkish fleet in the Battle of Navarino (today Pylos on the Peloponnese) during the Greek War of Liberation in 1827 and had been raised under the Greek King Otto, son of Ludwig I, and sold as recycled material in Europe, some of which ended up in Bavaria.

The place where the monumental statue was made is still commemorated today by Münchner Erzgießereistraße and the parallel Sandstraße, where the sand pit required for the casting was located.

From June to August, the parts of the Bavaria were transported to the installation site on specially constructed carts, each pulled by twelve horses.

The ceremonial unveiling finally took place on October 9 after a procession of all trades and guilds to Theresienwiese and, as expected, turned into a celebration of homage to the abdicated king.

The artists, whom the king had greatly supported during the years of his reign and provided with commissions through his lively building activities, paid special tribute to Ludwig.

"[7] In 1878, Georg von Hauberrisser submitted a design for the development of the eastern Theresienwiese planned from the 1870s onwards, which envisaged an oval boundary for the remaining open space, with all roads leading radially towards the Bavaria.

To partially finance the restoration work, the association produced replicas of the only Schwanthaler model, the tip of the statue's little finger in various scales, including as a drinking vessel, and other artisanal rarities, which were sold together with a publication.

In the course of the renovation work, which was immediately initiated and cost around one million euros, not only was the raised arm extensively stabilized and the entire outer surface cleaned, sanded and sealed, but a completely new spiral staircase was also installed.

The Bavaria 2000 association, which under its presidents Adi Thurner and later Erwin Schneider († 2005) had campaigned for the memory of King Ludwig I and the preservation of his buildings and monuments, was dissolved in 2006.

On the one hand, they developed various plans for the redesign of the Theresienwiese fairgrounds, including the Bavaria and the Ruhmeshalle, which lacked any respect for the site and the intentions of its builder.

In 1935, another plan was submitted that called for the demolition of the Bavaria and the Ruhmeshalle and the construction of a huge congress hall with a heroes' memorial in their place.

On the other hand, the open space of the Theresienwiese and the existing representative and symbolic architecture was often used for propagandistic displays, for example for mass events at the May Day rallies, which were celebrated with great fanfare until the outbreak of war, as the following excerpt from a report in the gleichgeschaltete Presse about the celebrations on May Day 1934 shows:"In the meantime, the enormous march to the afternoon rally on the Theresienwiese began.

Half an hour later, the members of all the student corporations of Munich's universities marched in with their banners to line up at the foot of the columns of the Ruhmeshalle.