Bayes' theorem

Based on Bayes' law, both the prevalence of a disease in a given population and the error rate of an infectious disease test must be taken into account to evaluate the meaning of a positive test result and avoid the base-rate fallacy.

Bayes used conditional probability to provide an algorithm (his Proposition 9) that uses evidence to calculate limits on an unknown parameter.

After Bayes's death, his family gave his papers to a friend, the minister, philosopher, and mathematician Richard Price.

Price significantly edited the unpublished manuscript for two years before sending it to a friend who read it aloud at the Royal Society on 23 December 1763.

Price wrote an introduction to the paper that provides some of the philosophical basis of Bayesian statistics and chose one of the two solutions Bayes offered.

In 1765, Price was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society in recognition of his work on Bayes's legacy.

[5][6] On 27 April, a letter sent to his friend Benjamin Franklin was read out at the Royal Society, and later published, in which Price applies this work to population and computing 'life-annuities'.

[9] About 200 years later, Sir Harold Jeffreys put Bayes's algorithm and Laplace's formulation on an axiomatic basis, writing in a 1973 book that Bayes' theorem "is to the theory of probability what the Pythagorean theorem is to geometry".

[13] Martyn Hooper[14] and Sharon McGrayne[15] have argued that Richard Price's contribution was substantial: By modern standards, we should refer to the Bayes–Price rule.

Price discovered Bayes's work, recognized its importance, corrected it, contributed to the article, and found a use for it.

The modern convention of employing Bayes's name alone is unfair but so entrenched that anything else makes little sense.[15]F.

Thomas Bruss reviewed Bayes' work "An essay towards solving a problem in the doctrine of chances" as communicated by Price.

[20] Modern Markov chain Monte Carlo methods have boosted the importance of Bayes' theorem, including in cases with improper priors.

Suppose, a particular test for whether someone has been using cannabis is 90% sensitive, meaning the true positive rate (TPR) = 0.90.

Therefore, it leads to 90% true positive results (correct identification of drug use) for cannabis users.

Which can then be used to calculate the probability of having cancer when you have the symptoms: A factory produces items using three machines—A, B, and C—which account for 20%, 30%, and 50% of its output, respectively.

This problem can also be solved using Bayes' theorem: Let Xi denote the event that a randomly chosen item was made by the i th machine (for i = A,B,C).

Bayes' theorem links the degree of belief in a proposition before and after accounting for evidence.

If the coin is flipped a number of times and the outcomes observed, that degree of belief will probably rise or fall, but might remain the same, depending on the results.

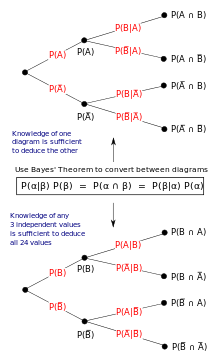

In such situations the denominator of the last expression, the probability of the given evidence B, is fixed; what we want to vary is A. Bayes' theorem shows that the posterior probabilities are proportional to the numerator, so the last equation becomes: In words, the posterior is proportional to the prior times the likelihood.

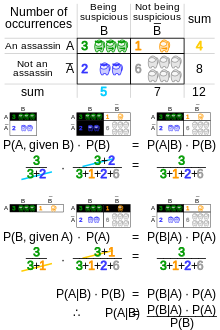

The example above can also be understood with more solid numbers: assume the patient taking the test is from a group of 1,000 people, 91 of whom have the disease (prevalence of 9.1%).

simultaneously: which (at least when having ruled out explosive antecedents) captures the classical contraposition principle Bayes' theorem represents a special case of deriving inverted conditional opinions in subjective logic expressed as: where

on which all probabilities are conditioned: Using the chain rule And, on the other hand The desired result is obtained by identifying both expressions and solving for

Many people seek to assess their chances of being affected by a genetic disease or their likelihood of being a carrier for a recessive gene of interest.

A Bayesian analysis can be done based on family history or genetic testing to predict whether someone will develop a disease or pass one on to their children.

Based solely on the status of the subject's siblings and parents, she is equally likely to be a carrier as to be a non-carrier (this likelihood is denoted by the Prior Hypothesis).

Cystic fibrosis is a heritable disease caused by an autosomal recessive mutation on the CFTR gene,[29] located on the q arm of chromosome 7.

To establish prior probabilities, a Punnett square is used, based on the knowledge that neither parent was affected by the disease but both could have been carriers: Homozygous for the wild-type allele (a non-carrier) Heterozygous(a CF carrier) Homozygous for the wild-type allele (a non-carrier) Heterozygous (a CF carrier) (affected by cystic fibrosis) Given that the patient is unaffected, there are only three possibilities.

After carrying out the same analysis on the patient's male partner (with a negative test result), the chance that their child is affected is the product of the parents' respective posterior probabilities for being carriers times the chance that two carriers will produce an affected offspring (1⁄4).

Cystic fibrosis, for example, can be identified in a fetus with an ultrasound looking for an echogenic bowel, one that appears brighter than normal on a scan.