Belgium in World War I

The history of Belgium in World War I traces Belgium's role between the German invasion in 1914, through the continued military resistance and occupation of the territory by German forces to the armistice in 1918, as well as the role it played in the international war effort through its African colony and small force on the Eastern Front.

[5] The German invaders treated any resistance—such as demolition of bridges and rail lines—as illegal and subversive, shooting the offenders and burning buildings in retaliation.

[9][10] In the spring of 1915, German authorities started construction on the Wire of Death, a lethal electric fence along the Belgian-Dutch border which would claim the lives of between 2,000 and 3,000 Belgian refugees trying to escape the occupied country.

Lack of effort was a form of passive resistance; Kossmann says that for many Belgians the war years were "a long and extremely dull vacation.

From top to bottom, there was a firm belief that the Belgians had unleashed illegal saboteurs (called "francs-tireurs") and that civilians had tortured and maltreated German soldiers.

[15] In addition some high-profile Belgian figures, including politician Adolphe Max and historian Henri Pirenne, were imprisoned in Germany as hostages.

The German position was that widespread sabotage and guerrilla activities by Belgian civilians were wholly illegal and deserved immediate harsh collective punishment.

Recent research that systematically studied German Army sources has demonstrated that they in fact encountered no irregular forces in Belgium during the first two and a half months of the invasion.

Published in May 1915, the Report provided elaborate details and first-hand accounts, including excerpts from diaries and letters found on captured German soldiers.

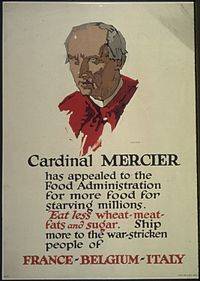

[21] As chairman of the CRB, Hoover worked with Francqui to raise money and support overseas, transporting food and aid to Belgium which was then distributed by the CNSA.

"[23] The prewar Catholic ministry remained in office as a government in exile with Charles de Broqueville continuing as prime minister and also taking on the war portfolio.

The two main opposition leaders, Paul Hymans of the Liberals and Emile Vandervelde of the Labour party, became ministers without portfolio in 1914.

The government was based in the French city of Le Havre, but communications with the people behind German lines were difficult and roundabout.

[35] King Albert I stayed in the Yser as commander of the military to lead the army while the Belgian government, under Charles de Broqueville withdrew to Le Havre in France.

At the Battle of Liège, the town's fortifications held off the invaders for over a week, buying valuable time for Allied troops to arrive in the area.

The dual significance of the battle was that the Germans were unable to complete their occupation of the entire country, and the Yser area remained unoccupied.

They formed part of the Belgian-French-British Army Group Flanders under command of King Albert I of Belgium and his French Chief of Staff General Jean Degoutte.

They played an important part in the Fifth Battle of Ypres, in which they breached the German lines at Houthulst and conquered Passchendaele, Langemark and Zonnebeke.

Next to Force Publique troops at the African theatre, thirty-two Congolese residents in Belgium were part of the Belgian Army and participated in the war at the Western Front in Europe.

[40] King Albert I went to the Paris Peace Conference in April 1919, where he met with the Big Four and the other leaders of France, Italy, Britain and the United States.

[41] He also considered that the dethronement of the princes of Central Europe and, in particular, the dissolution of the Habsburg Empire would constitute a serious menace to peace and stability on the continent.

[42] The Allies considered Belgium to be the chief victim of the war, and it aroused enormous popular sympathy, but the King's advice played a small role in Paris.

[43] Belgium was given much less than it wanted, with a total payment of three billion German gold marks ($500 million in 1919; $8,787,000,000 in 2025);[citation needed] the money did not stimulate the lethargic Belgian economy of the 1920s.

As outlined in the Treaty of Versailles, Belgium was also given a League of Nations mandate over the former German colonies in Africa of Rwanda and Burundi.

In the British Empire and America, poppies became a symbol of human life lost in war and were adopted as an emblem of remembrance from 1921.

The Ypres League transformed the horrors of trench warfare into a spiritual quest in which British and Imperial troops were purified by their sacrifice.

After the war Ypres became a pilgrimage destination for Britons to imagine and share the sufferings of their men and gain a spiritual benefit.