Belle Époque

Occurring during the era of the French Third Republic, it was a period characterised by optimism, enlightenment, regional peace, economic prosperity, nationalism, colonial expansion, and technological, scientific and cultural innovations.

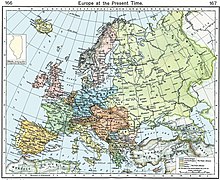

The Belle Époque was a period in which, according to historian R. R. Palmer, "European civilisation achieved its greatest power in global politics, and also exerted its maximum influence upon peoples outside Europe.

"[1] Two devastating world wars and their aftermath made the Belle Époque appear to be a time of joie de vivre (joy of living) in contrast to 19th century hardships.

It was also a period of stability that France enjoyed after the tumult of the early years of the Third Republic, featuring defeat in the Franco-Prussian War, the uprising of the Paris Commune, and the fall of General Georges Ernest Boulanger.

[3] Poverty remained endemic in Paris's urban slums and rural peasantry for decades after the Belle Époque ended.

Those who were able to benefit from the prosperity of the era were drawn towards new forms of light entertainment during the Belle Époque, and the Parisian bourgeoisie, or the successful industrialists called the nouveaux riches, became increasingly influenced by the habits and fads of the city's elite social class, known popularly as Tout-Paris ("all of Paris", or "everyone in Paris").

Belle Époque dancers and singers such as Polaire, Mistinguett, Paulus, Eugénie Fougère, La Goulue and Jane Avril were Paris celebrities, some of whom modelled for Toulouse-Lautrec's iconic poster art.

Large public buildings such as the Opéra Garnier devoted enormous spaces to interior designs as Art Nouveau show places.

After the mid-19th century, railways linked all the major cities of Europe to spa towns like Biarritz, Deauville, Vichy, Arcachon and the French Riviera.

Their carriages were rigorously divided into first-class and second-class, but the super-rich now began to commission private railway coaches, as exclusivity as well as display was a hallmark of opulent luxury.

The Paris Métro underground railway system joined the omnibus and streetcar in transporting the working population, including those servants who did not live in the wealthy centers of cities.

Meanwhile, the international workers' movement also reorganised itself and reinforced pan-European, class-based identities among the classes whose labour supported the Belle Époque.

Antisemitism directed at Dreyfus, and tolerated by the general French public in everyday society, was a central issue in the controversy and the court trials that followed.

[11] In fact, militarism and international tensions grew considerably between 1897 and 1914, and the immediate prewar years were marked by a general armaments competition in Europe.

Most of the great powers (and some minor ones such as Belgium, the Netherlands, or Denmark) became involved in imperialism, building their own overseas empires especially in Africa and Asia.

The cinématographe was invented in France by Léon Bouly and put to use by Auguste and Louis Lumière, brothers who held the first film screenings in the world.

Although Impressionism in painting began well before the Belle Époque, it had initially been met with scepticism if not outright scorn by a public accustomed to the realist and representational art approved by the Academy.

Artists who appealed to the Belle Époque public include William-Adolphe Bouguereau, the English Pre-Raphaelite's John William Waterhouse, and Lord Leighton and his depictions of idyllic Roman scenes.

Many successful examples of Art Nouveau, with notable regional variations, were built in France, Germany, Belgium, Spain, Austria (the Vienna Secession), Hungary, Bohemia, Serbia, and Latvia.

Joris-Karl Huysmans, who came to prominence in the mid-1880s, continued experimenting with themes and styles that would be associated with Symbolism and the Decadent movement, mostly in his book à rebours.

Although Baudelaire's poetry collection Les Fleurs du mal had been published in the 1850s, it exerted a strong influence on the next generation of poets and artists.

The Decadent movement fascinated Parisians, intrigued by Paul Verlaine and above all Arthur Rimbaud, who became the archetypal enfant terrible of France.

Free verse and typographic experimentation also emerged in Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira le hasard by Stéphane Mallarmé, anticipating Dada and concrete poetry.

Cosmopolis: An International Monthly Review had a far-reaching impact on European writers, and ran editions in London, Paris, Saint Petersburg, and Berlin.

Theatre adopted new modern methods, including Expressionism, and many playwrights wrote plays that shocked contemporary audiences either with their frank depictions of everyday life and sexuality or with unusual artistic elements.

Many Belle Époque composers working in Paris are still popular today: Igor Stravinsky, Erik Satie, Claude Debussy, Lili Boulanger, Jules Massenet, César Franck, Camille Saint-Saëns, Gabriel Fauré and his pupil, Maurice Ravel.

[13] According to Fauré and Ravel, the favoured composer of the Belle Époque was Edvard Grieg, who enjoyed the height of his popularity in both Parisian concert and salon life (despite his stance on the accused in the Dreyfus affair).

Ravel and Frederick Delius agreed that French music of this time was simply "Edvard Grieg plus the third act of Tristan".

Dancer Loie Fuller appeared at popular venues such as the Folies Bergère, and took her eclectic performance style abroad as well.