Benedict Arnold

This monument was erected under the patronage of the State of Connecticut in the 55th year of the Independence of the U.S.A. in memory of the brave patriots massacred at Fort Griswold near this spot on the 6th of Sept.

He conducted operations that provided the Americans with relief during the Siege of Fort Stanwix, and key actions during the pivotal 1777 Battles of Saratoga in which he sustained leg injuries that put him out of combat for several years.

[9] In 1755, Arnold was attracted by the sound of a drummer and attempted to enlist in the provincial militia for service in the French and Indian War, but his mother refused permission.

[16] Some sources allege that on one of his voyages he fought a duel in Honduras with a British sea captain who had called him a "damned Yankee, destitute of good manners or those of a gentleman".

He was convicted of disorderly conduct and fined the relatively small amount of 50 shillings; publicity of the case and widespread sympathy for his views probably contributed to the light sentence.

He wrote that he was "very much shocked" and wondered "good God, are the Americans all asleep and tamely giving up their liberties, or are they all turned philosophers, that they don't take immediate vengeance on such miscreants?

They issued him a colonel's commission on May 3, 1775, and he immediately rode off to Castleton in the disputed New Hampshire Grants (Vermont) in time to participate with Ethan Allen and his men in the capture of Fort Ticonderoga.

[37] He took the opportunity to visit his children while near his home in New Haven, and he spent much of the winter socializing in Boston, where he unsuccessfully courted a young belle named Betsy Deblois.

Washington refused his offer to resign, and wrote to members of Congress in an attempt to correct this, noting that "two or three other very good officers" might be lost if they persisted in making politically motivated promotions.

[41] He led a small contingent of militia attempting to stop or slow the British return to the coast in the Battle of Ridgefield,[42][43] and was again wounded in his left leg.

[45] Amid negotiations over that issue, Arnold wrote out a letter of resignation on July 11, the same day that word arrived in Philadelphia that Fort Ticonderoga had fallen to the British.

[55] Historian John Shy states: Arnold began planning to capitalize financially on the change in power in Philadelphia, even before the Americans reoccupied their city.

Or was it a kind of extreme midlife crisis, swerving from radical political beliefs to reactionary ones, a change accelerated by his marriage to the very young, very pretty, very Tory Peggy Shippen?

General Washington gave him a light reprimand, but it merely heightened Arnold's sense of betrayal; nonetheless, he had already opened negotiations with the British before his court martial even began.

"[68] A few days later, Arnold wrote to Greene and lamented over the "deplorable" and "horrid" situation of the country at that particular moment, citing the depreciating currency, disaffection of the army, and internal fighting in Congress, while predicting "impending ruin" if things did not change soon.

[78] Arnold's court martial on charges of profiteering began meeting on June 1, 1779, but it was delayed until December 1779 by Clinton's capture of Stony Point, New York, throwing the army into a flurry of activity to react.

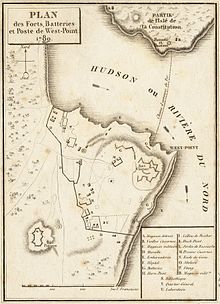

On June 16, Arnold inspected West Point while on his way home to Connecticut to take care of personal business, and he sent a highly detailed report through the secret channel.

[89] Arnold's command at West Point also gave him authority over the entire American-controlled Hudson River, from Albany down to the British lines outside New York City.

His subordinates, some long-time associates, grumbled about Arnold's unnecessary distribution of supplies and eventually concluded that he was selling them on the black market for personal gain.

[91] On August 30, Arnold sent a letter accepting Clinton's terms and proposing a meeting to André through yet another intermediary: William Heron, a member of the Connecticut Assembly whom he thought he could trust.

On the morning of September 22, from their position at Teller's Point, two American rebels (under the command of Colonel James Livingston), John "Jack" Peterson and Moses Sherwood, fired on HMS Vulture, the ship that was intended to carry André back to New York.

[101] Arnold learned of André's capture the morning of September 24 while waiting for Washington, with whom he was going to have breakfast at his headquarters in British Colonel Beverley Robinson's former summer house on the east bank of the Hudson.

[110] He also wrote in the letter to Washington requesting safe passage for Peggy: "Love to my country actuates my present conduct, however it may appear inconsistent to the world, who very seldom judge right of any man's actions.

[118] Other attempts all failed to gain positions within the government or the British East India Company over the next few years, and he was forced to subsist on the reduced pay of non-wartime service.

[139] Arnold was aware of his reputation in his home country, and French statesman Talleyrand described meeting him in Falmouth, Cornwall in 1794: The innkeeper at whose place I had my meals informed me that one of his lodgers was an American general.

[142] Social historian Brian Carso notes that, as the 19th century progressed, the story of Arnold's betrayal was portrayed with near-mythical proportions as a part of the national history.

Harper's Weekly published an article in 1861 describing Confederate leaders as "a few men directing this colossal treason, by whose side Benedict Arnold shines white as a saint".

It described a boy who stole eggs from birds' nests, pulled wings off insects, and engaged in other sorts of wanton cruelty, who then grew up to become a traitor to his country.

His difficult time in New Brunswick led historians to summarize it as full of "controversy, resentment, and legal entanglements" and to conclude that he was disliked by both Americans and Loyalists living there.

[157] The house where Arnold lived at 62 Gloucester Place in central London bears a plaque describing him as an "American Patriot",[158] in the sense that he "felt that what he was doing was in the interest of America".

This monument was erected under the patronage of the State of Connecticut in the 55th year of the Independence of the U.S.A. in memory of the brave patriots massacred at Fort Griswold near this spot on the 6th of Sept. AD 1781, when the British, under the command of the Traitor Benedict Arnold , burnt the towns of New London and Groton and spread desolation and woe throughout the region.