Berber kings of Roman-era Tunisia

The commoner Tacfarinas raised a revolt in defense of Berber land rights and became a great tribal chief as a result of his insurgency (17-24 AD) against Rome.

When it fell to the Romans the great city had become mostly a burning ruin, and the long rivalry between the two major powers of the western Mediterranean came to an end.

Berber relations with Rome became multivalent and fluid, characterized variously as a working alliance, functional ambivalence, partisan hostility, veiled maneuvering, and fruitful intercourse.

Markedly influenced by Punic civilization, they had nonetheless endured as separate Berber entities, their culture surviving throughout the long reign of Carthage.

Since the Numidian titles of the offices mentioned (GLD, MSSKWI, GZBI, GLDGIML) were not translated into Punic but left in a Berber language, it suggests an indigenous development.

During the battle, his cavalry engaged in fighting disappeared from Scipio's view, but at a crucial moment suddenly reappeared, attacking the Punic forces and gaining victory.

[16] The Roman writer Livy (59 BC – 17 AD) in his history of Rome, Ab urbe condita, devotes a half-dozen pages to Masinissa's character and career, both turbulent and admired, eventful and long in duration.

A modern Latin scholar summarizes as follows, citing Livy's Ab urbe condita: Masinissa is in fact a foreigner with almost all the Roman virtues.

Livy (59 BC – 17 AD), the Roman historian, presents a rather detailed portrait of these circumstances, especially events following the defeat of her husband Syphax.

Throughout he remained a faithful ally of Rome....[28]The isle of Delos was long famous as a cultural center of Ancient Greece, where its deities and acclaimed mortals were honored.

The three statues of Masinissa at Delos mentioned in the above text were erected on behalf of the kingdom of Bithynia in Anatolia, the isle of Rhodes, and the city of Athens.

"As an established king, [Masinissa] carefully cultivated the image of the perfect Hellenistic monarch through his coinage and the participation of at least one of his sons in the Panathenaic games.

Government institutions were established, evidently having an independent Berber origin, although informed by Punic civil traditions; indeed, Masinissa encouraged the cultural influence of Carthage.

It was a grandson of his that was organizing the defense of Carthage, and the king himself, who saw the fruits of his ambitions now snatched from his grasp, was somewhat cold when asked for assistance; when later he proffered it, he was told abruptly that the Romans would let him know when they needed help.

The Greek historian Polybius (c. 200–118 BC) praised him highly in his Histories, in a text that might be regarded as an obituary for the celebrated Berber leader: Massanissa, the king of the Numidians in Africa, one of the best and most fortunate men of our time, reigned for over sixty years, enjoying excellent health and attaining a great age, for he lived till ninety.... And he could also continue to ride hard by night and day without feeling any the worse.

Livy gives the Roman view of the king's character when he imagines Hasdrubal saying of the young Numidian: "Masinissa was a man of far loftier spirit and far greater ability than had ever been seen in anyone of his nation....he had often given evidence to friends and enemies alike of a valour rare amongst men.

Jugurtha's evident talents were a cause of concern to Micipsa, who accordingly sent him to Hispania to serve the Romans in their war against Numantia, which ended in 133 BC.

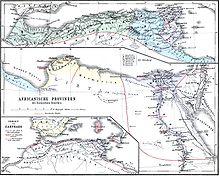

Farther west, Tingis (modern Tangier) was the capital of another Berber realm comprising western Mauretania, under its king, Bogud, brother of Bocchus I.

In part due to the favors he gave to Roman politicians, Jugurtha had managed to enlarge the scope of his power; yet eventually his dealings resulted in a notorious bribery scandal at Rome.

Jugurtha's assassinations of his regal cousins, his military aggression and overreach, and his slaughter of Italian traders at Cirta led to war with Rome.

A wealthy novus homo and populares, Marius was the first Roman general to enlist proletari (landless citizens) into his army; as a politician he was chosen Consul an unprecedented seven times (107, 104–100, 86), but his career ended badly.

On the opposing side politically, the optimate Lucius Cornelius Sulla Felix, later Consul (88, 80), and Dictator (82–79), had served as quaestor under Marius in Numidia.

In 88 BC after Sulla's army entered Rome nearly unopposed, the aging Marius was forced to flee to Africa to seek asylum.

[54] Decades later, the Numidian king Juba I (r. 60–46) played a significant role in Rome's civil wars, contested by arms between Pompey and Julius Caesar.

[55][56] In 47 BC, Julius Caesar and his forces landed in Africa in pursuit of Pompey's remnant army, which was headquartered at Utica near Carthage.

Bocchus II favored Octavius, Julius Caesar's adopted son, later renowned as Augustus, but Bogud inclined to Antonius.

[67][68][69] The unpopular reign of his son Ptolemy [Ptolemaeus] (r.23–40 AD) provoked an increase in Berber support for the rebel forces of Tacfarinas (see below).

Tacfarinas was not born a king or into a royal or a noble bloodline, but a Berber commoner who fought against the Roman Empire in order to maintain tribal grazing rights to land.

Eventually he led a large tribal confederacy, with assistance from neighboring Berber kingdoms, which for many years sustained a major conflict against Rome.

Accordingly, many ordinary Italians and various peoples of the Empire immigrated there to work and live; the wealthy sent agents with investment funds to purchase and manage the land; those with political influence might have been similarly favored.