Bernardino of Siena

Bernardino of Siena, OFM (Bernardine or Bernadine;[1][2] 8 September 1380 – 20 May 1444), was an Italian Catholic priest and Franciscan missionary preacher in Italy.

His preaching, his book burnings, and his "bonfires of the vanities" established his reputation in his own lifetime; they were frequently directed against gambling, infanticide, sorcery/witchcraft, sodomy (chiefly among homosexual males), Jews, Romani "Gypsies", usury, and the like.

Bernardino was canonised by Pope Nicholas V in 1450 and is referred to as "the Apostle of Italy" for his efforts to revive the country's Catholicism during the 15th century.

Another important contemporary biographical source is that written by the Sienese diplomat Leonardo Benvoglienti, who was another personal acquaintance of Bernardino's.

[4] The historian Franco Mormando notes that "[t]he first works to be produced about Bernardine right after his death [in 1444] were biographical: by the year 1480, there were already over a dozen written accounts of the preacher's life".

In 1397, after a course of civil and canon law, he joined the Confraternity of Our Lady attached to the hospital of Santa Maria della Scala.

Three years later, when the plague visited Siena, he ministered to the plague-stricken, and, assisted by ten companions, took upon himself for four months entire charge of this hospital.

He was an elegant and captivating preacher, and his use of popular imagery and creative language drew large crowds to hear his reflections.

"Bonfires of the Vanities" were held at his sermon sites,[7] where people threw mirrors, high-heeled shoes, perfumes, locks of false hair, cards, dice, chess pieces, and other frivolities to be burned.

Bernardino enjoined his listeners to abstain from blasphemy, indecent conversation, and games of chance, and to observe feast days.

Though, in his compassion for her, Bernardine would have the woman's domestic and social 'cage' be as comfortable and as humane as possible, it is there in the same traditional cage that Bernardino nonetheless wants her to remain, under the guard of father, brother, husband, or parish priest.

[23] Over time his teachings helped mould public sentiment and dispel indifference over controlling sodomy and homosexual conduct more vigorously.

Everything unpredictable or calamitous in human experience he attributed to sodomy, including floods and the plague, as well as linking the practice to local population decline.

[28] Usury was one of the principal objects of Bernardino's attacks, and he did much to prepare the way for the establishment of the beneficial loan societies, known as Monti di Pietà.

[7] Bernardino followed the earlier scholastic philosophers Anselm of Canterbury and Thomas Aquinas (who quotes Aristotle) in condemning the practice of usury, which they defined as charging interest on a loan.

In Milan, he was visited by a merchant who urged him to inveigh strenuously against usury, only to find that his visitor was himself a prominent usurer, whose activities were prompted by a wish to lessen competition.

Blaming the poverty of local Christians on Jewish usury, his call for Jews to be banished and isolated from their wider communities led to segregation.

Instead of one hundred and thirty Friars constituting the Observance in Italy at Bernardino's reception into the order, it counted over four thousand shortly before his death.

Having in 1442 persuaded the Pope to finally accept his resignation as Vicar-General so that he might give himself more undividedly to preaching, Bernardino again resumed his missionary work.

Despite the papal bull issued by Pope Eugene IV in 1443, Illius qui se pro divini, which charged Bernardino to preach the indulgence for the Crusade against the Turks, there is no record of his having done so.

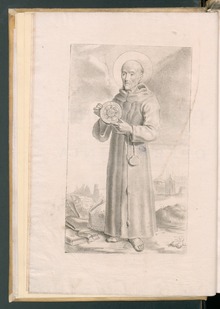

Mormando observes that "Bernardino's lifetime coincided with the blossoming not only of art in general but also of full-fledged, realistic portraiture as a distinct genre.

Many of the earliest portraits were presumably based on his death mask..."[33] Bernardino also lived into the early days of the print and was the subject of portraits in his lifetime, as well as a death-mask, which were copied to make prints, so that he is one of the earliest saints to have a fairly consistent appearance in art; though many Baroque images, such as that by El Greco, are idealized compared to the realistic ones made in the decades after his death.

[35] He appears to have been a favourite in the works of Luca della Robbia, and one of the finest examples of Renaissance art includes relief carvings of the saint, which can be seen in the oratory of Perugia Cathedral.

The most famous depictions of Bernardino are found in the cycle of frescoes of his life, which were executed towards the end of the fifteenth century by Pinturicchio in the Bufalini Chapel of Santa Maria in Aracoeli, Rome.

He is the patron saint of Carpi, Italy; the Philippine barangays of Kay-Anlog in Calamba, Laguna and Tuna in Cardona, Rizal; and the diocese of San Bernardino, California, USA.

The mountain pass in the Alps, Il Passo di San Bernardino, is named in honour of the saint, whose fame reached well into northern Italy and southern Switzerland.

[36] His cult also spread to England at an early period, and was particularly promulgated by the Observant Friars, who first established themselves in the country in Greenwich, in 1482, not forty years after his death, but who were later suppressed.