Geometric phase

In classical and quantum mechanics, geometric phase is a phase difference acquired over the course of a cycle, when a system is subjected to cyclic adiabatic processes, which results from the geometrical properties of the parameter space of the Hamiltonian.

[1] The phenomenon was independently discovered by S. Pancharatnam (1956),[2] in classical optics and by H. C. Longuet-Higgins (1958)[3] in molecular physics; it was generalized by Michael Berry in (1984).

Geometric phase around the conical intersection involving the ground electronic state of the C6H3F3+ molecular ion is discussed on pages 385–386 of the textbook by Bunker and Jensen.

Apart from quantum mechanics, it arises in a variety of other wave systems, such as classical optics.

As a rule of thumb, it can occur whenever there are at least two parameters characterizing a wave in the vicinity of some sort of singularity or hole in the topology; two parameters are required because either the set of nonsingular states will not be simply connected, or there will be nonzero holonomy.

The geometric phase occurs when both parameters are changed simultaneously but very slowly (adiabatically), and eventually brought back to the initial configuration.

In quantum mechanics, this could involve rotations but also translations of particles, which are apparently undone at the end.

One might expect that the waves in the system return to the initial state, as characterized by the amplitudes and phases (and accounting for the passage of time).

However, if the parameter excursions correspond to a loop instead of a self-retracing back-and-forth variation, then it is possible that the initial and final states differ in their phases.

To measure the geometric phase in a wave system, an interference experiment is required.

The Foucault pendulum is an example from classical mechanics that is sometimes used to illustrate the geometric phase.

The phase obtained has a contribution from the state's time evolution and another from the variation of the eigenstate with the changing Hamiltonian.

However, if the variation is cyclical, the Berry phase cannot be cancelled; it is invariant and becomes an observable property of the system.

An easy explanation in terms of geometric phases is given by Wilczek and Shapere:[7] How does the pendulum precess when it is taken around a general path C?

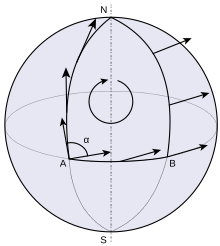

Finally, we can approximate any loop by a sequence of geodesic segments, so the most general result (on or off the surface of the sphere) is that the net precession is equal to the enclosed solid angle.To put it in different words, there are no inertial forces that could make the pendulum precess, so the precession (relative to the direction of motion of the path along which the pendulum is carried) is entirely due to the turning of this path.

For the original Foucault pendulum, the path is a circle of latitude, and by the Gauss–Bonnet theorem, the phase shift is given by the enclosed solid angle.

At the latitude of Paris, 48 degrees 51 minutes north, a full precession cycle takes just under 32 hours, so after one sidereal day, when the Earth is back in the same orientation as one sidereal day before, the oscillation plane has turned by just over 270 degrees.

Nonetheless, since the pendulum bob's plane of swing has shifted, the conservation laws imply that an exchange must have occurred.

Rather than tracking the change of momentum, the precession of the oscillation plane can efficiently be described as a case of parallel transport.

For that, it can be demonstrated, by composing the infinitesimal rotations, that the precession rate is proportional to the projection of the angular velocity of Earth onto the normal direction to Earth, which implies that the trace of the plane of oscillation will undergo parallel transport.

After 24 hours, the difference between initial and final orientations of the trace in the Earth frame is α = −2π sin φ, which corresponds to the value given by the Gauss–Bonnet theorem.

A simple method employing parallel transport within cones tangent to the Earth's surface can be used to describe the rotation angle of the swing plane of Foucault's pendulum.

Consider a planar pendulum with constant natural frequency ω in the small angle approximation.

The path is closed, since initial and final directions of the light coincide, and the polarization is a vector tangent to the sphere.

There are no forces that could make the polarization turn, just the constraint to remain tangent to the sphere.

Thus the polarization undergoes parallel transport, and the phase shift is given by the enclosed solid angle (times the spin, which in case of light is 1).

They showed that such cyclic attractors exist in a class of nonlinear dissipative systems with certain symmetries.

For time-reversal symmetrical electronic Hamiltonians the geometric phase reflects the number of conical intersections encircled by the loop.

The energy quantization condition obtained by solving Schrödinger's equation reads, for example,

picked up by the electron while it executes its (real-space) motion along the closed loop of the cyclotron orbit.