Siege

Siege warfare (also called siegecrafts or poliorcetics) is a form of constant, low-intensity conflict characterized by one party holding a strong, static, defensive position.

[2] This is typically coupled with attempts to reduce the fortifications by means of siege engines, artillery bombardment, mining (also known as sapping), or the use of deception or treachery to bypass defenses.

While traditional sieges do still occur, they are not as common as they once were due to changes in modes of battle, principally the ease by which huge volumes of destructive power can be directed onto a static target.

In Shang dynasty China, at the site of Ao, large walls were erected in the 15th century BC that had dimensions of 20 m (66 ft) in width at the base and enclosed an area of some 1,900 m (2,100 yd) squared.

Unlike the ancient Minoan civilization, the Mycenaean Greeks emphasized the need for fortifications alongside natural defences of mountainous terrain, such as the massive Cyclopean walls built at Mycenae and other adjacent Late Bronze Age (c. 1600–1100 BC) centers of central and southern Greece.

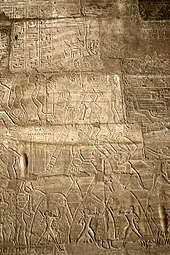

Later Egyptian temple reliefs of the 13th century BC portray the violent siege of Dapur, a Syrian city, with soldiers climbing scale ladders supported by archers.

In ancient China, sieges of city walls (along with naval battles) were portrayed on bronze 'hu' vessels, like those found in Chengdu, Sichuan in 1965, which have been dated to the Warring States period (5th to 3rd centuries BC).

An attacker – aware of a prolonged siege's great cost in time, money, and lives – might offer generous terms to a defender who surrendered quickly.

[8] As a siege progressed, the surrounding army would build earthworks (a line of circumvallation) to completely encircle their target, preventing food, water, and other supplies from reaching the besieged city.

The Hittite siege of a rebellious Anatolian vassal in the 14th century BC ended when the queen mother came out of the city and begged for mercy on behalf of her people.

Battering rams and siege hooks could also be used to force through gates or walls, while catapults, ballistae, trebuchets, mangonels, and onagers could be used to launch projectiles to break down a city's fortifications and kill its defenders.

In particular, medieval fortifications became progressively stronger—for example, the advent of the concentric castle from the period of the Crusades—and more dangerous to attackers—witness the increasing use of machicolations and murder-holes, as well the preparation of hot or incendiary substances.

A more detailed historical account from the 8th century BC, called the Piankhi stela, records how the Nubians laid siege to and conquered several Egyptian cities by using battering rams, archers, and slingers and building causeways across moats.

His engineers built a causeway that was originally 60 m (200 ft) wide and reached the range of his torsion-powered artillery, while his soldiers pushed siege towers housing stone throwers and light catapults to bombard the city walls.

In his Commentarii de Bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic War), Caesar describes how, at the Battle of Alesia, the Roman legions created two huge fortified walls around the city.

The Sicarii Zealots who defended Masada in AD 73 were defeated by the Roman legions, who built a ramp 100 metres (330 ft) high up to the fortress's west wall.

Much of this success in defense lay in the world's first use of gunpowder (i.e. with early flamethrowers, grenades, firearms, cannons, and land mines) to fight back against the Khitans, the Tanguts, the Jurchens, and then the Mongols.

Written later c. 1350 in the Huo Long Jing, this manuscript of Jiao Yu recorded an earlier Song-era cast-iron cannon known as the 'flying-cloud thunderclap eruptor' (fei yun pi-li pao).

If ten of these shells are fired successfully into the enemy camp, the whole place will be set ablaze...[21] During the Ming dynasty (AD 1368–1644), the Chinese were very concerned with city planning in regards to gunpowder warfare.

In 1453, the Theodosian Walls of Constantinople, the capital of the Roman Empire, were broken through in just six weeks by the 62 cannons of Mehmed II's army, although in the end the conquest was a long and extremely difficult siege with heavy Ottoman casualties due to the repeated attempts at taking the city by assault.

If necessary, using the first artillery fire for cover, the forces conducting the siege would repeat the process until they placed their guns close enough to be laid (aimed) accurately to make a breach in the fortifications.

For example, in Spain, the newly equipped army of Ferdinand and Isabella was able to conquer Moorish strongholds in Granada in 1482–1492 that had held out for centuries before the invention of cannons.

In the early 15th century, Italian architect Leon Battista Alberti wrote a treatise entitled De Re aedificatoria, which theorized methods of building fortifications capable of withstanding the new guns.

Nonetheless, innumerable large and impressive fortresses were built throughout northern Italy in the first decades of the 16th century to resist repeated French invasions that became known as the Italian Wars.

On 15 April 1746, the day before the Battle of Culloden, at Dunrobin Castle, a party of William Sutherland's militia conducted the last siege fought on the mainland of Great Britain against Jacobite members of Clan MacLeod.

Despite its excellent performance, the garrison's food supply had been requisitioned for earlier offensives, a relief expedition was stalled by the weather, ethnic rivalries flared up between the defending soldiers, and a breakout attempt failed.

The great Maginot Line was bypassed, and battles that would have taken weeks of siege could now be avoided with the careful application of air power (such as the German paratrooper capture of Fort Eben-Emael, Belgium, early in World War II).

During the peak of the battle, ARVN had access to only one 105 mm howitzer to provide close support, while the enemy attack was backed by an entire artillery division.

Most standoffs end in a peaceful resolution (i.e. 1973 Brooklyn hostage crisis, 1997 Roby standoff), though some may end in a police or military assault (i.e. 1994 Air France Flight 8969 hijacking, 1980 Iranian Embassy siege) or, in the worst-case scenarios, the deaths of authorities, hostage-takers, or hostages (i.e. 1985 MOVE bombing, 1985 EgyptAir Flight 648 hijacking, 2004 Beslan school siege, 2022 Robb Elementary School shooting).

The aforementioned worst-case scenarios often result from poor planning, tactics, or negotiations on the part of the authorities (e.g. accidental killings of hostages by Unit 777 during the EgyptAir Flight 648 hijacking), or from violent acts committed by the hostage-takers (e.g. suicide bombings and executions during the Beslan school siege).