Bilingual interactive activation plus

The BIA+ is one of many models that was defined based on data from psycholinguistic or behavioral studies which investigate how the languages of bilinguals are manipulated during listening, reading and speaking each of them; however, BIA+ is now being supported by neuroimaging data linking this model to more neurally inspired ones which have a greater focus on the brain areas and mechanisms involved in these tasks.

When used together, however, these two methods can generate a more complete picture of the time course and interactivity of bilingual language processing according to the BIA+ model.

[1] These methods, however, do need to be considered carefully as overlapping activation areas in the brain do not imply that there is no functional separation between the two languages at the neuronal or higher-order level.

[4] This theory was tested with orthographic neighbors, words of the same length that differ by one letter only (e.g. BALL and FALL).

Parallel access assumes that language is nonselective and that both potential word choices are activated in the bilingual brain when exposed to the same stimulus.

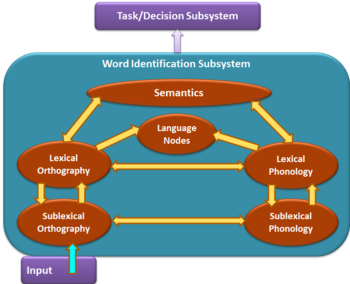

The task/decision subsystem of the BIA+ model determines which actions must be executed for the task at hand based on the relevant information that becomes available after word identification processing.

Action plans that meet the task at hand are executed by the task/decision system on the basis of activation information from the word identification subsystem.

[10] Therefore, the action plans of the task/decision system have no direct influence on activations of word identification language subsystem.

The neural correlates of the task/ decision subsystem consist of multiple components that map onto different areas of prefrontal cortex responsible for executing control functions.

This information would then be stored in the bilingual’s working memory and used in the task/decision system to determine which of the two translations best fits the task at hand.

Not only have studies suggested that the executive functioning of bilingualism extends beyond the language system, but bilinguals have also been shown to be faster processors who display fewer conflict effects than monolinguals in attentional tasks[16] This research implies that there may be some spillover effects of learning a second language on other areas of cognitive function that could be explored.