Resting potential

Conventionally, resting membrane potential can be defined as a relatively stable, ground value of transmembrane voltage in animal and plant cells.

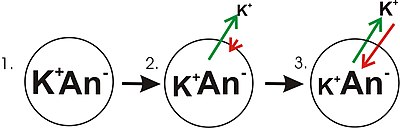

In the case of the resting membrane potential across an animal cell's plasma membrane, potassium (and sodium) gradients are established by the Na+/K+-ATPase (sodium-potassium pump) which transports 2 potassium ions inside and 3 sodium ions outside at the cost of 1 ATP molecule.

So, although there is an electric potential across the membrane due to charge separation, there is no actual measurable difference in the global concentration of positive and negative ions across the membrane (as it is estimated below), that is, there is no actual measurable charge excess on either side.

The resting voltage is the result of several ion-translocating enzymes (uniporters, cotransporters, and pumps) in the plasma membrane, steadily operating in parallel, whereby each ion-translocator has its characteristic electromotive force (= reversal potential = 'equilibrium voltage'), depending on the particular substrate concentrations inside and outside (internal ATP included in case of some pumps).

How the concentrations of ions and the membrane transport proteins influence the value of the resting potential is outlined below.

As ENa and EK were equal but of opposite signs, halfway in between is zero, meaning that the membrane will rest at 0 mV.

Such situation with similar permeabilities for counter-acting ions, like potassium and sodium in animal cells, can be extremely costly for the cell if these permeabilities are relatively large, as it takes a lot of ATP energy to pump the ions back.

The outward movement of positively charged potassium ions is due to random molecular motion (diffusion) and continues until enough excess negative charge accumulates inside the cell to form a membrane potential which can balance the difference in concentration of potassium between inside and outside the cell.

"Balance" means that the electrical force (potential) that results from the build-up of ionic charge, and which impedes outward diffusion, increases until it is equal in magnitude but opposite in direction to the tendency for outward diffusive movement of potassium.

A good approximation for the equilibrium potential of a given ion only needs the concentrations on either side of the membrane and the temperature.

It can be calculated using the Nernst equation: where Potassium equilibrium potentials of around −80 millivolts (inside negative) are common.

For common usage the Nernst equation is often given in a simplified form by assuming typical human body temperature (37 °C), reducing the constants and switching to Log base 10.

For Potassium at normal body temperature one may calculate the equilibrium potential in millivolts as: Likewise the equilibrium potential for sodium (Na+) at normal human body temperature is calculated using the same simplified constant.

If calculating the equilibrium potential for calcium (Ca2+) the 2+ charge halves the simplified constant to 30.77 mV.

Under normal conditions, it is safe to assume that only potassium, sodium (Na+) and chloride (Cl−) ions play large roles for the resting potential: This equation resembles the Nernst equation, but has a term for each permeant ion.

Also, z has been inserted into the equation, causing the intracellular and extracellular concentrations of Cl− to be reversed relative to K+ and Na+, as chloride's negative charge is handled by inverting the fraction inside the logarithmic term.

Medical conditions such as hyperkalemia in which blood serum potassium (which governs [K+]o) is changed are very dangerous since they offset Eeq,K+, thus affecting Em.

The use of a bolus injection of potassium chloride in executions by lethal injection stops the heart by shifting the resting potential to a more positive value, which depolarizes and contracts the cardiac cells permanently, not allowing the heart to repolarize and thus enter diastole to be refilled with blood.

/K +

-ATPase , as well as effects of diffusion of the involved ions, are major mechanisms to maintain the resting potential across the membranes of animal cells.