Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary

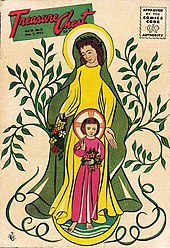

Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary is an autobiographical comic by American cartoonist Justin Green, published in 1972.

Green takes the persona of Binky Brown to tell of the "compulsive neurosis" with which he struggled in his youth and which he blamed on his strict Catholic upbringing.

Binky Brown had an immediate influence on contemporaries in underground comix: such cartoonists as Aline Kominsky, Robert Crumb, and Art Spiegelman soon turned to producing similarly confessional works.

[6] He dropped out of an MFA program at Syracuse University[7] when in 1968 he felt a "call to arms"[5] to move to San Francisco, where the nascent underground comix scene was blossoming amid the counterculture there.

[5] That year Green introduced a religion-obsessed character in the strip "Confessions of a Mad School Boy", published in a periodical in Providence, Rhode Island, in 1968.

These objects include Binky's fingers, toes, and his own penis, and he obsessively tries to deflect their "pecker rays" from reaching holy items such as churches or statues of Mary.

The narrator tells us that bad acid trips were like "water off a duck's back" to Binky, since everyday routines were already potentially traumatic experiences.

Emboldened by this, Binky confronts his faith and by smashing a set of miniature statues of the Virgin Mary, he declares himself free of his obsession with sexual purity.

[19] In the opening, the adult Binky hangs over a sickle, bound from head to toe and listening to Ave Maria as he draws with a pen in his mouth.

[3] He justifies the work to communicate with the "many others [who] are slaves to their neuroses" and who, despite believing themselves isolated, number so many that they "would entwine the globe many times over in a vast chain of common suffering".

[22] Other references to comics include a Sinstopper's Guidebook, which alludes to Dick Tracy's Crimestopper's Textbook[21] and a cartoon by Robert Crumb in the background.

In contrast to the mundane tales of Harvey Pekar, another prominent early practitioner of autobiographical comics, Green makes wide use of visual metaphors.

[9] Literary scholar Hillary Chute sees the work as addressing feminist concerns of "embodiment and representation"[27] as it "delves into and forcefully pictures non-normative sexuality".

[27] Chute affirms that despite its brevity Binky Brown merits the label "graphic novel" as "the quality of work, its approach, parameters, and sensibility"[5] mark a "seriousness of purpose".

[28] The story has had a wide influence on underground and alternative comics,[10] where its self-mocking[21] and confessional approach has inspired numerous cartoonists to expose intimate and embarrassing details of their lives.

Spiegelman delivered the three-page "Maus" in which Nazi cats persecute Jewish mice, inspired by his father's experiences in the Auschwitz concentration camp; years later he revisited the theme in the graphic novel of the same name.

[34] Comics critic Jared Gardner asserts that, while underground comix was associated with countercultural iconoclasm, the movement's most enduring legacy was to be autobiography.

[25] Green used the Binky Brown persona over the years in short strips and prose pieces that appeared in underground periodicals such as Arcade and Weirdo.

[45] Binky Brown Meets the Holy Virgin Mary has appealed mostly to comics fans and cartoonists, and has gained little recognition from mainstream audiences and arts critics.

[25] According to underground comix historian Patrick Rosenkranz, Green represents a break with past convention by being "the first to openly render his personal demons and emotional conflicts within the confines of a comic".

[13] Chute sees major themes of isolation and coping with OCD recurring in autobiographical works such as Howard Cruse's Stuck Rubber Baby (1995) and Alison Bechdel's Fun Home (2006).

[46] British-American cartoonist Gabrielle Bell sympathized with Brown's approach, which she described as "talking about his feelings or his emotional state when he was illustrating it with striking images that were sort of absurd or a weird juxtaposition".

[47] Green's influence extended overseas to cartoonists such as the Dutch Peter Pontiac, who drew inspiration from Binky Brown and Maus to produce Kraut (2000), about his father who collaborated with the Nazis during World War II.