Bioaerosol

A well-known case was the meningococcal meningitis outbreak in sub-Saharan Africa, which was linked to dust storms during dry seasons.

[2] Another instance was an increase in human respiratory problems in the Caribbean that may have been caused by traces of heavy metals, microorganism bioaerosols, and pesticides transported via dust clouds passing over the Atlantic Ocean.

Charles Darwin was the first to observe the transport of dust particles[3] but Louis Pasteur was the first to research microbes and their activity within the air.

Survival rate of bioaerosols depends on a number of biotic and abiotic factors which include climatic conditions, ultraviolet (UV) light, temperature and humidity, as well as resources present within dust or clouds.

[6] Pollen grains are the largest bioaerosols and are less likely to remain suspended in the air over a long period of time due to their weight.

[1] Consequently, pollen particle concentration decreases more rapidly with height than smaller bioaerosols such as bacteria, fungi and possibly viruses, which may be able to survive in the upper troposphere.

However, some particularly resilient fungal bioaerosols have been shown to survive in atmospheric transport despite exposure to severe UV light conditions.

[citation needed] Unlike other bioaerosols, bacteria are able to complete full reproductive cycles within the days or weeks that they survive in the atmosphere, making them a major component of the air biota ecosystem.

The inoculum yielded cycle thresholds between 20 and 22, similar to those observed in human upper and lower respiratory tract samples.

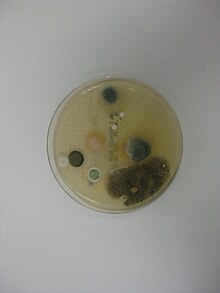

[10] To collect bioaerosols falling within a specific size range, impactors can be stacked to capture the variation of particulate matter (PM).

Variations such as the 7-day recording volumetric spore trap have been designed for continuous sampling using a slowly rotating drum that deposits impacted material onto a coated plastic tape.

[14] Instead of collecting onto a greased substrate or agar plate, impingers have been developed to impact bioaerosols into liquids, such as deionized water or phosphate buffer solution.

Collection efficiencies of impingers are shown by Ehrlich et al. (1966) to be generally higher than similar single stage impactor designs.

The use of low-volume liquids is ideal for minimising sample dilution, and has the potential to be couple to lab-on-chip technologies for rapid point-of-care analysis.

Once airborne they typically remain in the planetary boundary layer (PBL), but in some cases reach the upper troposphere and stratosphere.

Bioaerosols introduced to the atmosphere can form clouds, which are then blown to other geographic locations and precipitate out as rain, hail, or snow.

[21][22] One study concluded that a type of airborne bacteria present in a particular desert dust was found at a site 1,000 kilometers downwind.

[23] Bioaerosols impact a variety of biogeochemical systems on earth including, but not limited to atmospheric, terrestrial, and marine ecosystems.

Additionally, the distribution of pollen and spore bioaerosols contribute to the genetic diversity of organisms across multiple habitats.

Bioaerosols make up a small fraction of the total cloud condensation nuclei in the atmosphere (between 0.001% and 0.01%) so their global impact (i.e. radiation budget) is questionable.

[26] The types and sizes of bioaerosols vary in marine environments and occur largely because of wet-discharges caused by changes in osmotic pressure or surface tension.

This correlation was determined by the work of microbiologists and a Total Ozone Mapping Spectrometer, which identified bacteria, viral, and fungal bioaerosols in the dust clouds that were tracked over the Atlantic Ocean.

[27] Another instance in of this occurred in 1997 when El Niño possibly impacted seasonal trade wind patterns from Africa to Barbados, resulting in similar die offs.

[2] Another instance of bioaerosol-spread health issues was an increase in human respiratory problems for Caribbean-region residents that may have been caused by traces of heavy metals, microorganism bioaerosols, and pesticides transported via dust clouds passing over the Atlantic Ocean.

[5] Determining global interactions is possible through methods like collecting air samples, DNA extraction from bioaerosols, and PCR amplification.

[21] Developing more efficient modelling systems will reduce the spread of human disease and benefit economic and ecologic factors.

The ADMS 3 uses computational fluid dynamics (CFD) to locate potential problem areas, minimizing the spread of harmful bioaerosol pathogens include tracking occurrences.