Indoor bioaerosol

[3] Major indoor sources for bioaerosols at residential homes include human occupants, pets, house dust, organic waste, as well as the heating, ventilation and air-conditioning (HVAC) system.

[4] In a study by Wouters et al.,[6] they investigated the effects of indoor storage of organic household waste on microbial contamination among 99 households in the Netherlands in the summer of 1997, and indicated that "increased microbial contaminant levels in homes are associated with indoor storage of separated organic waste", which might elevate "the risk of bioaerosol-related respiratory symptoms in susceptible people".

However, the analysis by Wouters et al.[6] was based on the collected samples of settled house dust, which might not serve as a strong indicator for bioaerosols suspended in the air.

[4][10] For non-residential buildings, some specific indoor environments, such as hospitals, wastewater treatment plants, composting facilities, certain biotechnical laboratories, have been revealed to have bioaerosol sources related to their particular environmental characteristics.

[6] It is reported that 25%-30% of allergenic asthma cases in industrialised countries are induced by fungi,[17] which has been the focus of concerns about human exposure to airborne microorganisms in recent years.

[18] Some other human diseases and symptoms have been proposed to be associated with indoor bioaerosol, but no deterministic conclusions could be drawn due to the insufficiency of evidence.

[20][21][22][23] However, most of the related studies based their conclusions on statistical correlation between concentrations of certain types of bioaerosols and incidence of complaints, which has various drawbacks methodologically.

[3] Because of the confirmed and potential adverse health effects associated with indoor bioaerosol, some concentration limits for total number of bioaerosol particles are recommended by different agencies and organisations as follow: 1000 CFUs/m3 (National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)), 1000 CFUs/m3 (American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists (ACGIH)) with the culturable count for total bacteria not exceeding 500 CFUs/m3.

[5] In previous research on indoor bioaerosol in residential environments, microorganisms have been quantified by conventional culture-based techniques, in which colony forming units (CFU) on selective media are counted.

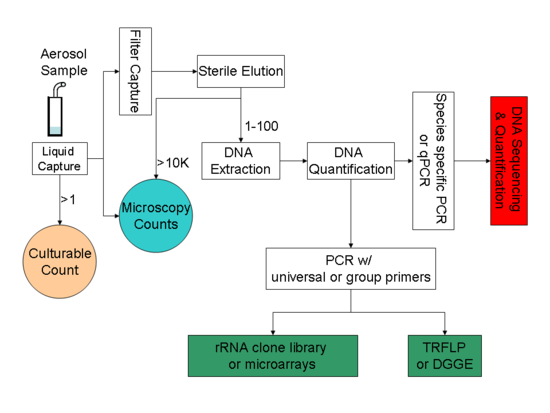

[29] Major culture-independent identification/quantification methods adopted in previous bioaerosol studies include polymerase chain reaction (PCR),[17] quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR),[32] microarray (PhyloChip),[33] fluorescent in situ hybridisation (FISH),[34] flow cytometry[34] and solid-phase cytometry,[18] immunoassay (i.e., enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)).

PCR alone cannot accomplish all the tasks related to bioaerosol detection; instead it usually serves as the preparation tool for subsequent processes like DNA sequencing, microarray, and community fingerprinting techniques.

Targeting the variation in the 16S rRNA gene, a microarray (PhyloChip) was used to conduct comprehensive identification of both bacterial and archaeal organisms in bioaerosols.

[5] In a study by Lange et al.,[34] FISH method successfully identified eubacteria in samples of complex native bioaerosols in swine barns.

Potentially effective strategies include: 1) limiting entrance of outdoor aerosols; 2) keeping the relative humidity level below high levels (<60%);[7] 3) installing appropriate filtration devices to air ventilation system to inlet filtered outdoor air into indoor environment; 4) reducing/removing contaminant sources (i.e., indoor organic waste).

[5] Current or developing indoor air purification technologies include filtration, aerosol ultraviolet irradiation, electrostatic precipitation, unipolar ion emission, and photocatalytic oxidation.