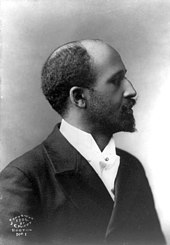

William Monroe Trotter

In Boston, Trotter succeeded in shutting down productions of The Clansman in 1910, but he was unsuccessful in 1915 with screenings of the movie The Birth of a Nation, which also portrayed the Ku Klux Klan in favorable terms.

After their first two children died in infancy, they returned to the Isaacs farm of Virginia's parents, where their son William Monroe Trotter was born on April 7, 1872.

When he was seven months old, the family moved back to Boston, where they settled in the South End, far from the predominantly African-American west side of Beacon Hill.

[13] The young Trotter (who was usually called by his middle name "Monroe") grew up in this environment, and was introduced to Archibald Grimké, another politically active African American who also lived in Hyde Park.

[17] Following his graduation, Trotter participated in the upper echelons of Negro society in Boston, a number of whose members had ancestors free before the Civil War.

[22] He finally landed a job in a white-owned real estate firm in 1898, but decided the next year to open his own business selling insurance and brokering mortgages.

He was not particularly active in agitating for civil rights in these years, although his strong opinions on racial equality were evident in an 1899 paper in which he called on African Americans to seek admission to institutions of higher learning.

[24] Washington actively promoted the idea that African Americans, once they had proven themselves as productive members of society, would be granted full political rights.

Du Bois, and other northern radicals disagreed with these ideas, arguing that it was necessary for African Americans to agitate for equal treatment and full constitutional rights, because doing so would bring other benefits.

At first Forbes, an Amherst College graduate with some experience in publishing, was the driving operational force in its production, while Trotter funded the effort and served as its managing editor.

[30] The paper became a forum for a more outspoken and forceful approach to gaining racial equality, and its contributors and editorials (which were generally written by Trotter) regularly attacked Washington.

[37][38] In the early 1900s Trotter noticed that racial segregation was spreading in Boston: the number of hotels, restaurants, and other public establishments refusing service to African Americans was increasing.

[43] At the group's annual meeting in Louisville, Kentucky, Trotter and others introduced resolutions calling for more activism, but Booker T. Washington supporters (also known as "Bookerites"), who controlled the council, saw to their defeat.

[47] Trotter and other radicals tended to come from the North, where African Americans exercised more rights in daily life, including the suffrage, were more urbanized, and had achieved more in work and education, but were still subject to discrimination.

Du Bois and Grimké were the two most radical leaders invited to its early organizational meetings, but both eventually refused to ally with Washington, whom they saw as dominating the group.

[57] Organized so that no one man could dominate it, the group espoused a radical declaration of principles (authored by Trotter and Du Bois), calling for agitation for equal economic opportunity and exercise of full civil rights for African Americans.

[68] He was also troubled by the attitudes expressed in the Boston chapter, which he told NAACP leader Joel Spingarn needed more "radical, courageous activity."

[75] As the NAACP attracted more money and talent, and became the center of anti-Bookerite civil rights activity, Trotter and the NIPL became increasingly marginalized on the left.

The NAACP and NERL (then known as the National Independent Political League, or NIPL) protested, and Trotter secured a meeting with Wilson at the White House in November 1913.

A white Texas newspaper described Trotter as "merely a nigger" and "not a Booker T. Washington type of colored man",[81] and Northern papers also criticized him for his "insolence" to the president.

[82] The Boston Evening Transcript, while observing that Wilson's policy was segregationist and divisive, pointed out that although Trotter was basically correct, he "offends many of his own color by his ... untactful belligerency".

[83] Trotter parlayed the publicity into a series of speaking engagements, in which he denied "that in language, manner, tone, in any respect or to the slightest degree I was impudent, insolent, or insulting to the President.

When the country began large-scale recruiting for the military in World War I, Trotter opposed the establishment of segregated officer training facilities.

[85] When the Great War ended, Trotter sought to use the 1919 Paris Peace Conference as a vehicle to raise international awareness of US government policy toward African Americans.

The State Department refused to issue passports to those delegates, or to African Americans planning to attend a Pan-African Congress that Du Bois was organizing to be held concurrently with the peace conference in Paris.

[87] To get to Europe, Trotter posed as a seaman seeking work in New York, and got a job as a cook on the SS Yarmouth to gain passage to France.

Trotter attracted the French press in his accounts of racial mistreatment in the United States, but he could not gain access to any of the official delegations to the peace conference.

Trotter quickly supported active resistance to white-on-black violence, writing, "Unless the white American behaves, he will find that in teaching our boys to fight for him he was starting something that he will not be able to stop.

"[91] His writings prompted calls in Congress for the censorship of the Negro press: South Carolina Congressman James F. Byrnes accused Trotter of "doing his utmost to incite riots and bloodshed.

In 1921, Trotter was successful in shutting down new screenings of The Birth of a Nation in Boston; he allied with Roman Catholic organizations, who objected to the KKK's anti-Catholic stance of the 20th century, and were strong in the city as a result of extensive Irish and Italian immigration.