Black Death

[9] The immediate territorial origins of the Black Death and its outbreak remain unclear, with some evidence pointing towards Central Asia, China, the Middle East, and Europe.

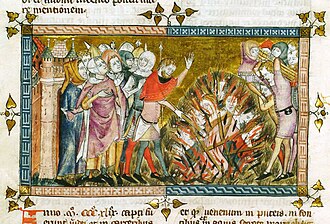

[10][11] The pandemic was reportedly first introduced to Europe during the siege of the Genoese trading port of Kaffa in Crimea by the Golden Horde army of Jani Beg in 1347.

From Crimea, it was most likely carried by fleas living on the black rats that travelled on Genoese ships, spreading through the Mediterranean Basin and reaching North Africa, West Asia, and the rest of Europe via Constantinople, Sicily, and the Italian Peninsula.

Homer used it in the Odyssey to describe the monstrous Scylla, with her mouths "full of black Death" (Ancient Greek: πλεῖοι μέλανος Θανάτοιο, romanized: pleîoi mélanos Thanátoio).

[33][b] In 1908, Gasquet said use of the name atra mors for the 14th-century epidemic first appeared in a 1631 book on Danish history by J. I. Pontanus: "Commonly and from its effects, they called it the black death" (Vulgo & ab effectu atram mortem vocitabant).

[37] Research in 2018 found evidence of Yersinia pestis in an ancient Swedish tomb, which may have been associated with the "Neolithic decline" around 3000 BCE, in which European populations fell significantly.

In 610, the Chinese physician Chao Yuanfang described a "malignant bubo" "coming in abruptly with high fever together with the appearance of a bundle of nodes beneath the tissue.

The authors concluded that this new research, together with prior analyses from the south of France and Germany, "ends the debate about the cause of the Black Death, and unambiguously demonstrates that Y. pestis was the causative agent of the epidemic plague that devastated Europe during the Middle Ages".

[33] Many scholars arguing for Y. pestis as the major agent of the pandemic suggest that its extent and symptoms can be explained by a combination of bubonic plague with other diseases, including typhus, smallpox, and respiratory infections.

[62] Currently, while osteoarcheologists have conclusively verified the presence of Y. pestis bacteria in burial sites across northern Europe through examination of bones and dental pulp, no other epidemic pathogen has been discovered to bolster the alternative explanations.

One irate Londoner complained that the runoff from the local slaughterhouse had made his garden "stinking and putrid", while another charged that the blood from slain animals flooded nearby streets and lanes, "making a foul corruption and abominable sight to all dwelling near."

But at length it came to Gloucester, yea even to Oxford and to London, and finally it spread over all England and so wasted the people that scarce the tenth person of any sort was left alive.

[98] The epidemic there killed the 13-year-old son of the Byzantine emperor, John VI Kantakouzenos, who wrote a description of the disease modelled on Thucydides's account of the 5th century BCE Plague of Athens, noting the spread of the Black Death by ship between maritime cities.

[104][105][106] According to some epidemiologists, periods of unfavorable weather decimated plague-infected rodent populations, forcing their fleas onto alternative hosts,[107] inducing plague outbreaks which often peaked in the hot summers of the Mediterranean[108] and during the cool autumn months of the southern Baltic region.

[112] The disease struck various regions in the Middle East and North Africa during the pandemic, leading to serious depopulation and permanent change in both economic and social structures.

[115] The historian al-Maqrizi described the abundant work for grave-diggers and practitioners of funeral rites; plague recurred in Cairo more than fifty times over the following one and a half centuries.

[72] Boccaccio's description: In men and women alike it first betrayed itself by the emergence of certain tumours in the groin or armpits, some of which grew as large as a common apple, others as an egg ... From the two said parts of the body this deadly gavocciolo soon began to propagate and spread itself in all directions indifferently; after which the form of the malady began to change, black spots or livid making their appearance in many cases on the arm or the thigh or elsewhere, now few and large, now minute and numerous.

And it is unerringly close to Froissart's claim that "a third of the world died," a measurement probably drawn from St. John's figure of mortality from plague in the Book of Revelation, a favorite medieval source of information.

[135] The mass burial sites that have been excavated have allowed archaeologists to continue interpreting and defining the biological, sociological, historical, and anthropological implications of the Black Death.

[135] The mortality rate of the Black Death in the 14th century was far greater than the worst 20th-century outbreaks of Y. pestis plague, which occurred in India and killed as much as 3% of the population of certain cities.

[136] Chalmel de Vinario recognised that bloodletting was ineffective (though he continued to prescribe bleeding for members of the Roman Curia, whom he disliked), and said that all true cases of plague were caused by astrological factors and were incurable; he was never able to effect a cure.

[142] Italian chronicler Agnolo di Tura recorded his experience from Siena, where plague arrived in May 1348: Father abandoned child, wife husband, one brother another; for this illness seemed to strike through the breath and sight.

[150] A study performed by Thomas Van Hoof of the Utrecht University suggests that the innumerable deaths brought on by the pandemic cooled the climate by freeing up land and triggering reforestation.

Because 14th-century healers and governments were at a loss to explain or stop the disease, Europeans turned to astrological forces, earthquakes and the poisoning of wells by Jews as possible reasons for outbreaks.

[157] One theory that has been advanced is that the Black Death's devastation of Florence, between 1348 and 1350, resulted in a shift in the world view of people in 14th-century Italy that ultimately led to the Renaissance.

[163][better source needed] Prior to the emergence of the Black Death, the continent was considered a feudalistic society, composed of fiefs and city-states frequently managed by the Catholic Church.

[164] The pandemic completely restructured both religion and political forces; survivors began to turn to other forms of spirituality and the power dynamics of the fiefs and city-states crumbled.

[164][165] The survivors of the pandemic found not only that the prices of food were lower but also that lands were more abundant, and many of them inherited property from their dead relatives, and this probably contributed to the destabilization of feudalism.

]At the close of the fourteenth century and during the course of the fifteenth the supply of ornaments, furniture, plate, statues painted or in highly decked "coats," with which the churches were literally encumbered as time went on, proved a striking contrast to the comparative simplicity which characterised former days, as witnessed by a comparison of inventories.[...

This led to the establishment of a Public Health Department there which undertook some leading-edge research on plague transmission from rat fleas to humans via the bacillus Yersinia pestis.