Black people and Mormonism

During the history of the Latter Day Saint movement, the relationship between Black people and Mormonism has included enslavement, exclusion and inclusion, and official and unofficial discrimination.

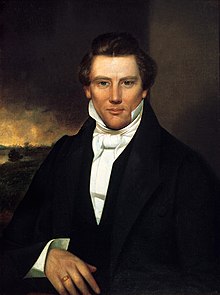

Mormonism founder Joseph Smith and his successor as church president with the most followers, Brigham Young, both taught that the skin color of Black people was the result of the curses of Cain and Ham.

[2]: 16 [10]: 5 During the Missouri years, he tried to maintain peace with the members' pro-slavery neighbors;[2]: 16 in 1835, the church declared it was not "right to interfere with bond-servants, nor baptize them contrary to the will and wish of their masters" or cause "them to be dissatisfied with their situations in this life.

By that year, LDS leaders justified discriminatory policies with the belief that the spirits of Black individuals before earthly life were "fence sitters" between God and the devil and were less virtuous than white souls.

[17]: 27 [21][22] A century later, in a 1949 statement, the First Presidency (the church's highest governing body) said that Black people were not entitled to the full blessings of the gospel and cited previous revelations on preexistence as justification.

[7]: 125 [36] Although LDS scriptures do not mention the skin color of Ham or that of his son, Canaan, some church teachings associated the Hamitic curse with Black people and used it to justify their enslavement.

[7]: 125 In 1978, when the church ended the temple and priesthood bans, apostle Bruce R. McConkie taught that the ancient curses of Cain and Ham were no longer in effect.

Brigham Young began teaching that enslaving people was ordained by God, but remained opposed to creating a slave-based economy in Utah.

[17]: 25 Many prominent church members enslaved people, including William H. Hooper, Abraham O. Smoot, Charles C. Rich, Brigham Young and Heber C.

[66][67] After the reversal of the temple and priesthood ban in 1978, LDS leaders were relatively silent about civil rights and eventually formed a partnership with the NAACP.

[69] The following year, it was announced that the church and the NAACP would begin a joint program for the financial education of East Coast residents in Baltimore, Atlanta and Camden, New Jersey.

"[73][74] That month, in a speech at BYU, apostle Dallin H. Oaks denounced racism, endorsed the message that "Black lives matter" (discouraging its use to advance controversial proposals), and called on church members to root out racist attitudes, behavior and policies.

[75][76] During the first century of its existence, the church discouraged social interaction or marriage with Black people[77][9]: 89 [78] and encouraged racial segregation in its congregations, facilities, and university, in medical blood supplies, and in public schools.

[18]: 1843 Until 1963, many church leaders supported legalized racial segregation; David O. McKay, J. Reuben Clark, Henry D. Moyle, Ezra Taft Benson, Joseph Fielding Smith, Harold B. Lee, and Mark E. Petersen were leading proponents.

"[9]: 70 Church leaders taught for over a century that the priesthood-ordination and temple-ordinance bans were commanded by God; according to Young, it was a "true eternal principle the Lord Almighty has ordained.

"[1]: 37 In 1949, the First Presidency under George Albert Smith released a statement that the restriction "remains as it has always stood" and was "not a matter of the declaration of a policy but of direct commandment from the Lord".

[7]: 222–223 [97][9]: 221 A second First Presidency statement twenty years later, under David O. McKay, re-emphasized that the "seeming discrimination by the Church towards the Negro is not something which originated with man; but goes back into the beginning with God".

[17] The LDS church has adapted to environmental pressures throughout its history, including going from polygamy to monogamy, from political separatism to assimilation with the United States, and from communitarian socialism to corporate capitalism.

[65]: 231 According to accounts by several present, the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles received the revelation to remove the racial restrictions while they prayed in the Salt Lake Temple.

[65]: 231–232 [111]: 94–95 Due to the publicity from Lester Bush's seminal article "Mormonism's Negro Doctrine" in 1973, BYU vice-president Robert Thomas feared that the church would lose its tax-exempt status.

[124] In 2022, BYU professor and Young Men general presidency member Brad Wilcox was criticized for a speech in which he downplayed and dismissed concerns about the priesthood and temple ban.

[125][126] Although Wilcox issued two apologies,[127] reporter Jana Riess wrote that his scornful tone and words indicated that he "felt disdainful toward women" and believed that "God is a racist".

[17]: 68 [131] A 1959 nationwide report by the United States Commission on Civil Rights found that Black people experienced widespread inequality in Utah, and Mormon teachings were used to justify racist treatment.

Smith wrote that racism persisted because church leadership had not addressed the ban's origins: the beliefs that Black people were descendants of Cain, that they were neutral in the war in heaven, and that skin color indicated righteousness.

Public pressure led the church to change the manual's digital version, which subsequently said that the nature and appearance of the mark of dark skin are not fully understood.

[152] Bruce R. McConkie wrote in his 1966 Mormon Doctrine, the "gospel message of salvation is not carried affirmatively to [Black people], although sometimes negroes search out the truth.

[81]: 80, 94 In Brazil, LDS officials discouraged people with Black ancestry from investigating the church; before World War II, proselytism in that country was limited to white German-speaking immigrants.

[172] However, Smith viewed white people as superior to Blacks and said that they must not "sacrifice the dignity, honor and prestige that may be rightfully attached to the ruling races.

[184] Historian Dale Morgan wrote in 1949, "An interesting feature of the Church's doctrine is that it discriminates in no way against ... members of other racial groups, who are fully admitted to all the privileges of the priesthood.

[17]: 68 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (Strangite), founded by James Strang in 1844, welcomed Black people at a time when other factions denied them the priesthood and other benefits of membership.