Blacksmith

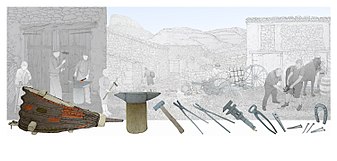

Blacksmiths produce objects such as gates, grilles, railings, light fixtures, furniture, sculpture, tools, agricultural implements, decorative and religious items, cooking utensils, and weapons.

[2] Blacksmiths work by heating pieces of wrought iron or steel until the metal becomes soft enough for shaping with hand tools, such as a hammer, an anvil and a chisel.

Heating generally takes place in a forge fueled by propane, natural gas, coal, charcoal, coke, or oil.

Even punching and cutting operations (except when trimming waste) by smiths usually re-arrange metal around the hole, rather than drilling it out as swarf.

As an example of drawing, a smith making a chisel might flatten a square bar of steel, lengthening the metal, reducing its depth but keeping its width consistent.

For example, in preparation for making a hammerhead, a smith would punch a hole in a heavy bar or rod for the hammer handle.

For example, to fashion a cross-peen hammer head, a smith would start with a bar roughly the diameter of the hammer face: the handle hole would be punched and drifted (widened by inserting or passing a larger tool through it), the head would be cut (punched, but with a wedge), the peen would be drawn to a wedge, and the face would be dressed by upsetting.

A smith would therefore frequently turn the chisel-to-be on its side and hammer it back down—upsetting it—to check the spread and keep the metal at the correct width.

To clean the faces, protect them from oxidation, and provide a medium to carry foreign material out of the weld, the smith sometimes uses flux—typically powdered borax, silica sand, or both.

Now the smith moves with rapid purpose, quickly taking the metal from the fire to the anvil and bringing the mating faces together.

A few light hammer taps bring the mating faces into complete contact and squeeze out the flux—and finally, the smith returns the work to the fire.

The fibrous nature of wrought iron required knowledge and skill to properly form any tool which would be subject to stress.

A supremely skilled artisan whose forge was a volcano, he constructed most of the weapons of the gods, as well as beautiful assistants for his smithy and a metal fishing-net of astonishing intricacy.

In Celtic mythology, the role of Smith is held by eponymous (their names do mean 'smith') characters : Goibhniu (Irish myths of the Tuatha Dé Danann cycle) or Gofannon (Welsh myths/ the Mabinogion).

[4] In the Nart mythology of the Caucasus the hero known to the Ossetians as Kurdalægon and the Circassians as Tlepsh is a blacksmith and skilled craftsman whose exploits exhibit shamanic features, sometimes bearing comparison to those of the Scandinavian deity Odin.

One of his greatest feats is acting as a type of male midwife to the hero Xamyc, who has been made the carrier of the embryo of his son Batraz by his dying wife the water-sprite Lady Isp, who spits it between his shoulder blades, where it forms a womb-like cyst.

Völundr eventually had his revenge by killing Níðuðr's sons and fashioning goblets from their skulls, jewels from their eyes and a brooch from their teeth.

He then raped the king's daughter, after drugging her with strong beer, and escaped, laughing, on wings of his own making, boasting that he had fathered a child upon her.

Seppo Ilmarinen, the Eternal Hammerer, blacksmith and inventor in the Kalevala, is an archetypal artificer from Finnish mythology.

Ogun, the god of blacksmiths, warriors, hunters and others who work with iron is one of the pantheon of Orisha traditionally worshipped by the Yoruba people of Nigeria.

During the (north) Polar Exploration of the early 20th century, Inughuit, northern Greenlandic Inuit, were found to be making iron knives from two particularly large nickel-iron meteors.

Although iron is quite abundant, good quality steel remained rare and expensive until the industrial developments of Bessemer process et al. in the 1850s.

[11] For example, in 1346 Katherine Le Fevre was appointed by Edward III to ‘keep up the king’s forge within the Tower and carry on [its] work … receiving the wages pertaining to the office’.

European blacksmiths before and through the medieval era spent a great deal of time heating and hammering iron before forging it into finished articles.

From a scientific point of view, the reducing atmosphere of the forge was both removing oxygen (rust), and soaking more carbon into the iron, thereby developing increasingly higher grades of steel as the process was continued.

During the eighteenth century, agents for the Sheffield cutlery industry scoured the British country-side, offering new carriage springs for old.

During the 1790s Henry Maudslay created the first screw-cutting lathe, a watershed event that signaled the start of blacksmiths being replaced by machinists in factories for the hardware needs of the populace.

Samuel Colt neither invented nor perfected interchangeable parts, but his insistence (and other industrialists at this time) that his firearms be manufactured with this property, was another step towards the obsolescence of metal-working artisans and blacksmiths.

In the final part of the 18th century, forged ironwork continued to decline due to the aforementioned industrial revolution, shapes of the elements in the designs of window grilles and other decorative functional items continued to contradict natural forms, surfaces begin to be covered in paint, cast iron elements are incorporated into the forged designs.

Main features of Neoclassicism ironwork (also referred to as Louis XVI style and Empire style ironwork) include smooth straight bars, decorative geometric elements, double or oval volutes and the usage of elements from Classical antiquity (Meander (art), wreaths etc.).