Bloomsbury Group

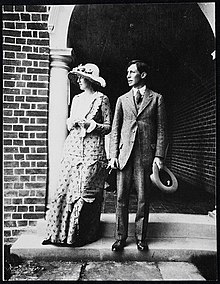

[1] Among the people involved in the group were Virginia Woolf, John Maynard Keynes, E. M. Forster, Vanessa Bell, and Lytton Strachey.

Their works and outlook deeply influenced literature, aesthetics, criticism, and economics, as well as modern attitudes towards feminism, pacifism, and sexuality.

"[3] The historian C. J. Coventry, resurrecting an older argument by Raymond Williams, disputes the existence of the group and the extent of its impact, describing it as "curio" for those interested in Keynes and Woolf.

[6][7] In 1905 Vanessa began the "Friday Club" and Thoby ran "Thursday Evenings", which became the basis for the Bloomsbury Group,[8] which to some was really "Cambridge in London".

[9] The Bloomsbury Group, mostly from upper middle-class professional families, formed part of "an intellectual aristocracy which could trace itself back to the Clapham Sect".

[6] It was an informal network[10][11] of an influential group of artists, art critics, writers and an economist, many of whom lived in the West Central 1 district of London known as Bloomsbury.

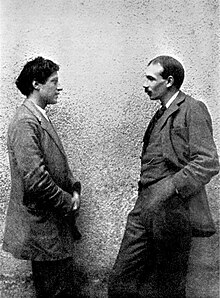

[13] Lytton Strachey[nb 1] and his cousin and lover Duncan Grant[18] became close friends of the Stephen sisters, Vanessa Bell and Virginia Woolf.

Duncan Grant had affairs with siblings Vanessa Bell and Adrian Stephen, as well as David Garnett, Maynard Keynes, and James Strachey.

[16] The lives and works of the group members show an overlapping, interconnected similarity of ideas and attitudes that helped to keep the friends and relatives together, reflecting in large part the influence of G. E. Moore: "the essence of what Bloomsbury drew from Moore is contained in his statement that 'one's prime objects in life were love, the creation and enjoyment of aesthetic experience and the pursuit of knowledge'".

For Moore, intrinsic value depended on an indeterminable intuition of good and a concept of complex states of mind whose worth as a whole was not proportionate to the sum of its parts.

[22] Bloomsbury reacted against current upper class English social rituals, "the bourgeois habits ... the conventions of Victorian life"[23] with their emphasis on public achievement, in favour of a more informal and private focus on personal relationships and individual pleasure.

As Virginia Woolf put it, their "triumph is in having worked out a view of life which was not by any means corrupt or sinister or merely intellectual; rather ascetic and austere indeed; which still holds, and keeps them dining together, and staying together, after 20 years".

Clive Bell polemicized[clarification needed] post-impressionism in his widely read book Art (1914), basing his aesthetics partly on Roger Fry's art criticism and G. E. Moore's moral philosophy; and as the war came he argued that "in these days of storm and darkness, it seemed right that at the shrine of civilization - in Bloomsbury, I mean - the lamp should be tended assiduously".

Desmond MacCarthy and Leonard Woolf engaged in friendly rivalry as literary editors, respectively of the New Statesman and The Nation and Athenaeum, thus fuelling animosities that saw Bloomsbury dominating the cultural scene.

[42] In the previous decade she had become one of the century's most famous feminist writers with three more novels, and a series of essays including the moving late memoir "A Sketch of the Past".

[citation needed] The diversity yet collectivity of Later Bloomsbury's ideas and achievements can be summed up in a series of credos that were made in 1938, the year of the Munich Agreement.

Virginia Woolf published her radical feminist polemic Three Guineas that shocked some of her fellow members, including Keynes who had enjoyed the gentler A Room of One's Own (1929).

Clive Bell published an appeasement pamphlet (he later supported the war), and E. M. Forster wrote an early version of his famous essay "What I Believe" with its choice of personal relations over patriotism: his quiet assertion in the face of the increasingly totalitarian claims of both left and right that "personal relations ... love and loyalty to an individual can run counter to the claims of the State".

[51] In his book on the background of the Cambridge spies, Andrew Sinclair wrote about the Bloomsbury group: "rarely in the field of human endeavour has so much been written about so few who achieved so little".