Kingdom of France

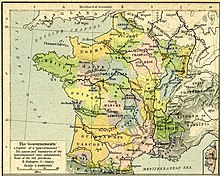

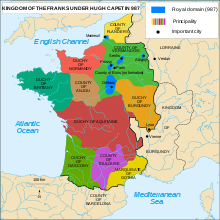

The Kingdom of France was descended directly from the western Frankish realm of the Carolingian Empire, which was ceded to Charles the Bald with the Treaty of Verdun (843).

From then, France was continuously ruled by the Capetians and their cadet lines under the Valois and Bourbon until the monarchy was abolished in 1792 during the French Revolution.

Emerging victorious from said conflicts, France subsequently sought to extend its influence into Italy, but after initial gains was defeated by Spain and the Holy Roman Empire in the ensuing Italian Wars (1494–1559).

France in the early modern era was increasingly centralised; the French language began to displace other languages from official use, and the monarch expanded his absolute power in an administrative system, known as the Ancien Régime, complicated by historic and regional irregularities in taxation, legal, judicial, and ecclesiastic divisions, and local prerogatives.

French intervention in the American Revolutionary War helped the United States secure independence from King George III and the Kingdom of Great Britain, but was costly and achieved little for France.

The Treaty of Verdun of 843 divided the Carolingian Empire into three parts, with Charles the Bald ruling over West Francia, the nucleus of what would develop into the kingdom of France.

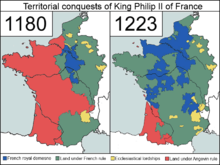

The area around the lower Seine became a source of particular concern when Duke William of Normandy took possession of the Kingdom of England by the Norman Conquest of 1066, making himself and his heirs the king's equal outside France (where he was still nominally subject to the Crown).

This, in addition to a long-standing dispute over the rights to Gascony in the south of France, and the relationship between England and the Flemish cloth towns, led to the Hundred Years' War of 1337–1453.

[10] The losses of the century of war were enormous, particularly owing to the plague (the Black Death, usually considered an outbreak of bubonic plague), which arrived from Italy in 1348, spreading rapidly up the Rhône valley and thence across most of the country: it is estimated that a population of some 18–20 million in modern-day France at the time of the 1328 hearth tax returns had been reduced 150 years later by 50 percent or more.

After the Hundred Years' War, Charles VIII of France signed three additional treaties with Henry VII of England, Emperor Maximilian I, and Ferdinand II of Aragon respectively at Étaples (1492), Senlis (1493) and Barcelona (1493).

A growing urban-based Protestant minority (later dubbed Huguenots) faced ever harsher repression under the rule of Francis I's son King Henry II.

France was expansive during all but the end of the seventeenth century: the French began trading in India and Madagascar, founded Quebec and penetrated the North American Great Lakes and Mississippi, established plantation economies in the West Indies and extended their trade contacts in the Levant and enlarged their merchant marine.

Henry IV's son Louis XIII and his minister (1624–1642) Cardinal Richelieu, elaborated a policy against Spain and the Holy Roman Empire during the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) which had broken out in Germany.

The Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659) formalised France's seizure (1642) of the Spanish territory of Roussillon after the crushing of the ephemeral Catalan Republic and ushered a short period of peace.

[17] The Ancien Régime, a French term rendered in English as "Old Rule", or simply "Former Regime", refers primarily to the aristocratic, social and political system of early modern France under the late Valois and Bourbon dynasties.

He sought to eliminate the remnants of feudalism still persisting in parts of France and, by compelling the noble elite to regularly inhabit his lavish Palace of Versailles, built on the outskirts of Paris, succeeded in pacifying the aristocracy, many members of which had participated in the earlier "Fronde" rebellion during Louis' minority.

It is estimated that anywhere between 150,000 and 300,000 Protestants fled France during the wave of persecution that followed the repeal,[20] (following "Huguenots" beginning a hundred and fifty years earlier until the end of the 18th century) costing the country a great many intellectuals, artisans, and other valuable people.

In this, he garnered the friendship of the papacy, which had previously been hostile to France because of its policy of putting all church property in the country under the jurisdiction of the state rather than that of Rome.

[22] The reign (1715–1774) of Louis XV saw an initial return to peace and prosperity under the regency (1715–1723) of Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, whose policies were largely continued (1726–1743) by Cardinal Fleury, prime minister in all but name.

But alliance with the traditional Habsburg enemy (the "Diplomatic Revolution" of 1756) against the rising power of Britain and Prussia led to costly failure in the Seven Years' War (1756–63) and the loss of France's North American colonies.

[25] On the eve of the French Revolution of July 1789, France was in a profound institutional and financial crisis, but the ideas of the Enlightenment had begun to permeate the educated classes of society.

The role of the King in France was finally ended with the execution of Louis XVI by guillotine on Monday, January 21, 1793, followed by the "Reign of Terror", mass executions and the provisional "Directory" form of republican government, and the eventual beginnings of twenty-five years of reform, upheaval, dictatorship, wars and renewal, with the various Napoleonic Wars.

However the deposed Emperor Napoleon I returned triumphantly to Paris from his exile in Elba and ruled France for a short period known as the Hundred Days.

His reign was characterized by disagreements between the Doctrinaires, liberal thinkers who supported the Charter and the rising bourgeoisie, and the Ultra-royalists, aristocrats and clergymen who totally refused the Revolution's heritage.

[28] The King abdicated, as did his son the Dauphin Louis Antoine, in favour of his grandson Henri, Count of Chambord, nominating his cousin the Duke of Orléans as regent.

[31] The conquest of Algeria continued, and new settlements were established in the Gulf of Guinea, Gabon, Madagascar, and Mayotte, while Tahiti was placed under protectorate.

[33] Louis Philippe appointed notable bourgeois as Prime Minister, like banker Casimir Périer, academic François Guizot, general Jean-de-Dieu Soult, and thus obtained the nickname of "Citizen King" (Roi-Citoyen).

What is now eastern France (Lorraine, Arelat) was not part of Western Francia to begin with and was only incorporated into the kingdom during the early modern period.

The ensuring French Wars of Religion, and particularly the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre, decimated the Huguenot community;[40] Protestants declined to seven to eight percent of the kingdom's population by the end of the 16th century.

The resulting exodus of Huguenots from the Kingdom of France created a brain drain, as many of them had occupied important places in society.