Medieval demography

It estimates and seeks to explain the number of people who were alive during the Medieval period, population trends, life expectancy, family structure, and related issues.

Serious gradual depopulation began in the West only in the 5th century and in the East due to the appearance of bubonic plague in 541 after 250 years of economic growth after the troubles which afflicted the empire from the 250s to 270s.

Some have connected this demographic transition to the Migration Period Pessimum,[clarification needed] when a decrease in global temperatures impaired agricultural yields.

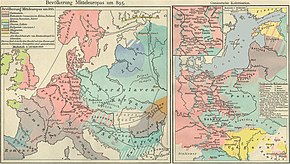

The Early Middle Ages saw relatively little population growth with urbanization well below its Roman peak, reflecting a low technological level, limited trade and political, social and economic dislocation exacerbated by the impact of Viking expansion in the north, Arab expansion in the south and the movement of Slavs and Bulgarians, and later the Magyars in the east.

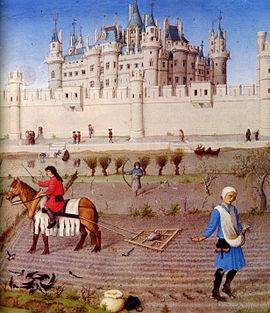

[1] Most medieval settlements remained small, with agricultural land and large zones of unpopulated and lawless wilderness in between (Geographers estimate that around 800, as much as three-quarters of Europe was still forested).

[6] At the same time, during the Ostsiedlung, Germans resettled east of the Elbe and Saale rivers, in regions previously only sparsely populated by Polabian Slavs.

[1] Towns and trade revived, and the rise of a money economy began to weaken the bonds of serfdom that tied peasants to the land.

[1] By the 14th century, the frontiers of settled cultivation had ceased to expand and internal colonization was coming to an end, but population levels remained high.

[1] Some have questioned the long-standing theory that the decline in population was caused only by infectious disease (see further discussions at Black Death) and so historians have examined other social factors, as follows.

A classic Malthusian argument has been put forward that Europe was overpopulated: even in good times it was barely able to feed its population.

)[1] Malnutrition developed gradually over decades, lowering resistance to disease, and competition for resources meant more warfare, and then finally crop yields were pushed down by the Little Ice Age.

The economic conditions of the poor also aggravated the calamities of the plague because they had no recourse, such as fleeing to a villa in the country in the manner of the nobles in the Decameron.

[1] This increased the mobility of labour and led to a redistribution of wealth, although property-owners' attempts to resist change through wage freezes and price controls[1] contributed to popular uprisings such as the Peasants' Revolt of 1381.

[1] Still yet another theory, as introduced by Robert Brenner in a 1976 paper, is that the economic system of the High Middle Ages limited population growth.

With any surplus of food, labor, and income absorbed by the landowners, the peasants did not have enough capital to invest in their farms or enough incentive to increase the productivity of their land.

In addition, the small size of most peasants' farms inhibited centralized and more efficient cultivation of land on larger fields.

Only through modifying the existing social structure of land ownership and distribution could Europe's population surpass early 14th century levels.

Descriptive accounts include those of chroniclers who wrote about the size of armies, victims of war or famine, participants in an oath.

[1] Manorial surveys were very common throughout the Middle Ages, in particular in France and England, but faded as serfdom gave way to a money economy.