Itinerant court

Itinerant courts were gradually replaced from the thirteenth century, when stationary royal residences began to develop into modern capital cities.

The itinerant court system of ruling a country is strongly associated with German history, where the emergence of a capital city took an unusually long time.

The German itinerant regime (Reisekönigtum) was the usual form of royal or imperial government from the Frankish period and up to late medieval times.

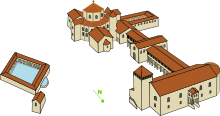

The Merovingian kings of the Frankish Empire already practiced this system, and the subsequent Carolingian dynasty adopted both the custom and its associated palaces (Kaiserpfalz, lit.

Royal pfalzes were scattered around the whole country—notably in accessible, fertile areas—and surrounded by imperial property administrated by the palace to ensure supplies.

However, these distances could not be maintained on all routes—there were large territories in which no royal pfalz or grange existed, or lacked nearby monasteries or towns.

Old bishoprics were often located in these places, another advantage in that bishops were usually more loyal to the king than regional dukes, who pursued their own dynastic goals.

Medieval Germany was, however, not the only kingdom ruled this way; it was also the case in most other contemporary European countries, where terms like "corte itinerante" describe this phenomenon.

Spain, on the other hand, lacked a fixed royal residence until the late 1500s, when Philip II elevated El Escorial outside Madrid to this rank.

[8] He made ten trips to the Low Countries, nine to German-speaking lands, seven to Spain, seven to Italian states, four to France, two to England, and two to North Africa.

But its very prosperity and its extensive and long-recognized liberties, the latter subsequently characterized in Magna Carta as 'ancient', forbade it as a desirable place of residence for the king and his court, preventing it from becoming a political capital.

They tried to find some other suitable place in the kingdom to deposit their archives, which were gradually growing too large and heavy to be transported on their unending journeys.

The Hundred Years' War against France caused the political center of gravity to shift to the southern parts of England, where London was dominant.

Gradually, many state institutions ceased to follow the king on his journeys and established themselves permanently in London: the Treasury, Parliament, and the court.

It was only possible for him to make London his capital city after he had become powerful enough to "tame the financial metropolis" and transform it into an obedient tool of the State's authority.

During medieval times, this "oral" culture gradually gave way to a "documentary" type of rule—one based on written communication, which generated archives, making stationary rule increasingly attractive to kings.